The following is the introduction from True Homosexual Experiences: Boyd McDonald and Straight to Hell, copyright © 2016 by William E. Jones. Reprinted by permission of the author and We Heard You Like Books. Available now.

Full of anticipation and unsure of what he is looking for, a young man enters an adult bookstore. Stepping through a creaky door bearing a warning sign (“no minors”) he heads for the magazine rack. Among the glossy full-color porno magazines giving off a chemical smell, he sees a small, pamphlet-sized publication called Straight to Hell. The title recalls condemnations such as “god hates fags,” but at the same time suggests defiance—anyone on the straight and narrow path can go to hell. The cover features an image of a naked man who looks nothing like a model, and may be an ex-convict. Not “fabulous” or campy, the booklet seems old-fashioned and homemade, the opposite of what the young man has been led to expect from gay culture. Inside the issue, there is a rhyming slogan in the masthead: “Love and Hate for the American Straight.”

Straight to Hell’s visual style is immediately recognizable yet anonymous, just like its contents. Lurid, tabloid-style headlines introduce texts contributed by the readers. They describe sex acts between men in many different settings, in various parts of the United States and the rest of the world. This comes as news to the young man: homosexuality is not just confined to a few neighborhoods in big cities and is more or less (for lack of a better word) ordinary. The young man shoplifts a copy of Straight to Hell, and at home he masturbates to the words and pictures. Though he doesn’t realize it at first, this small booklet has changed his life. On one page, there is an address, a post office box in New York City where he can send orders for more issues and submit his own sex stories. Accompanying the address is a name: Boyd McDonald.

Boyd McDonald, founding editor of Straight to Hell, was the main creative force behind one of the most distinctive underground publications, in fact, the first queer zine. Self-published and crude, Straight to Hell’s sense of urgency was as strong as its contempt for authority. Fanzines and underground comics of the 1960s and early 70s had combined these elements before, but none of them were devoted to homosexual material. From the 1950s onward, early gay publications (e. g., One, “The Homosexual Viewpoint” and Physique Pictorial) had used the same format—the size of an 8½ by 11 inch sheet of paper folded in half—but none of these prepared readers for Straight to Hell. The main difference from its predecessors was its attitude: the man who assembled this material just didn’t give a damn about any recognized standard of taste.

Issues of Straight to Hell were illustrated with beefcake photographs and candid shots of men. Most were by Bob Mizer of Athletic Model Guild or David Hurles of Old Reliable, but many other photographers and studios were represented. Even documentary photographs by Jack Delano from the Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Collection at the Library of Congress found their way into Boyd’s publications. Straight to Hell also published many amateur photos sent in by subscribers.

The unnamed men who contributed their stories came from all walks of life, barely literate to highly educated. Some were young, while others were old enough to remember the early years of the 20th Century. They all had one thing in common: a need to write accounts of their sexual exploits and share them with their fellow men. Boyd McDonald attached great importance to his undertaking; he once wrote, “I consider this history, not pornography. It’s very serious work… the true history of homosexual desire and experience. Any gay publications that do not deal with the elemental discussion of gay sexual desire are not serious—they are frivolous.” He collected sex stories from a multitude of men and kept his comments on them to a minimum.

Boyd McDonald reserved most of his editorial commentary for news items about the stupidity, hate, and war-mongering of American politicians, and he illustrated them with unflattering photographs. Boyd knew how to spot a con artist, especially one who had wrapped himself in the flag.

Boyd made his political opinions explicit, but he wrote about his personal life reluctantly. A brief account, varying only slightly over the years, became the basis of a compelling biographical myth. One “author’s bio” from the early 1980s is typical:

Boyd McDonald was born in South Dakota in 1925. “I was a pioneer high school dropout,” he writes, “leaving school to play badly in a bad traveling dance band. I was drafted into the Army, graduated from Harvard and came to New York, where my principal activity was taking advantage of the city’s public sexual recreation facilities. As a sideline I worked as a hack writer at Time, Forbes, IBM and even more sordid companies…. I started the magazine STH (Straight to Hell), The Manhattan Review of Unnatural Acts, later re-named The New York Review of Cocksucking….”

He describes pillars of the establishment as “sordid” and sends up The New York Review of Books by replacing “books” with “cocksucking,” a clear statement of priorities. The text is found at the back of the second anthology of “true homosexual experiences” drawn from the pages of Straight to Hell. Eventually 13 STH collections came out from various publishers. They all had concise, direct titles: Meat, Flesh, Sex, Cum, Smut, Juice, Wads, Cream, Filth, Skin, Raunch, Lewd, Scum. A number of proposed titles—Bare, Heat, Hoses, Sex Hounds, Sperm, Stuff, Tools, Used—remained unrealized at the time of Boyd’s death in 1993. These books contain descriptions of “how men look, act, walk, talk, dress, undress, taste and smell.” At first glance, Boyd’s publications might appear to be indistinguishable from the many subsequent ones that copied Straight to Hell to less effect and acclaim. A careful reading of STH reveals that its editor possessed a unique sensibility; his subversive wit graced every project on which he worked. Boyd had a reputation for being a curmudgeon, and beneath his polite demeanor was a fiercely individualistic anarchist.

In a recent biography, a bit of pleasure reading, I was struck by the phrase “improbably literate hustler,” the kind of expression that brings to mind Victorian pieties about a whore with a heart of gold. The writer’s assumption, presumably shared by many of his readers, is that for a biography to impart the greatest moral edification, the subject should be respectable (educated and not a whore) or filthy (not educated and a whore). The former kind of subject serves for inspirational stories (“someone just like me has succeeded”); the latter, for cautionary tales (“someone I wouldn’t want to be has failed”). The subject who confounds these categories poses difficulties, either when educated and a whore, i. e, unable to act in his or her best interests (a mentally ill person); or not educated and not a whore, i. e., childlike, unyielding, and inscrutable (a saint).

The homosexual, considered mentally ill until fairly recently in the United States, can disturb these comforting habits of mind. The suspicion that educated men were enjoying the company of hustlers when they weren’t toiling at their respectable jobs did not occur to the benighted American majority until the latter half of the 1960s, if then. With the arrival of AIDS in the US, an alarming number of homosexuals became physically ill, and the signs were unavoidable: uninhibited fraternizing between men of different ethnic groups and social classes had been taking place, often in public and even in broad daylight, for many years. Then AIDS killed all the really interesting people, and a group of jealous perverts who appointed themselves defenders of the American way of life unleashed a backlash. Those who came into this world after the worst years of the AIDS crisis may imagine that the moral panic is a thing of the past, like the witch trial, but anyone who lived through that time knows that moral entrepreneurs (when they aren’t occupied with stealing money and spending it on hustlers and drugs) are always looking for new excuses to spring into action.

The American puritanism nurturing moral panics also dictates that those with a sexual role in society—prostitutes, pornographers, promiscuous amateurs—cannot be taken seriously as artists. Discounting their work is merely an example of stereotypical thinking, the mob mentality enforcing conformity. The gay artists who really risked something—usually called erotic artists when not being prosecuted for obscenity, pandering, or endangering children—have only recently gained some credibility in American culture (e. g., books published and art exhibited). Considering the joyous recklessness of their lives, the erratic quality of medical care for any but the privileged in this country, and that their generation was already decimated by AIDS, they have come to seem like combat veterans, but without medals, because instead of foreign enemies, they have been fighting the prejudice, pettiness, and hypocrisy of American society. They have sacrificed everything so the rest of us can see photographs of naked thugs, experience vicariously the kind of sex sensible people hesitate to seek out, and read stories of their colorful lives in explicit detail. Some of them contributed to Straight to Hell; a few are still alive today. They deserve our respect and gratitude.

Almost infantile in its defiance and not respecting the boundaries between public and private, Straight to Hell is easy to dismiss as the work of an obsessive crank, yet within its pages enduring truths are found. Anyone can see this stuff is trash, but somehow it has never gone away; that is because the social ills Straight to Hell diagnoses have never gone away, either. As long as brain and genitals must coexist in the same body, in other words, as long as we are human, we must reckon with Boyd McDonald and his inconvenient messages.

Boyd McDonald wrote for most of his adult life, but while he acquired the proper credentials to participate in American literary culture, he ultimately rejected it. Off to one side, he observed the scene with anger and amusement. Boyd read The New York Review of Books and placed advertisements in it soliciting submissions to Straight to Hell; he read the New York Times, but an advertisement he intended for its pages was rejected because it consisted solely of the words “homosexual experiences” and Straight to Hell’s address; he wrote for Time and Forbes, and he later read them with a view to subjecting his former employers to caustic criticism. None of these publications ever mentioned or reviewed Boyd’s work during his lifetime, although Straight to Hell at the height of its popularity had a circulation of 20,000, and Meat, his most successful book, sold over 50,000 copies. Today these figures would qualify any sufficiently presentable writer or editor for literary stardom.

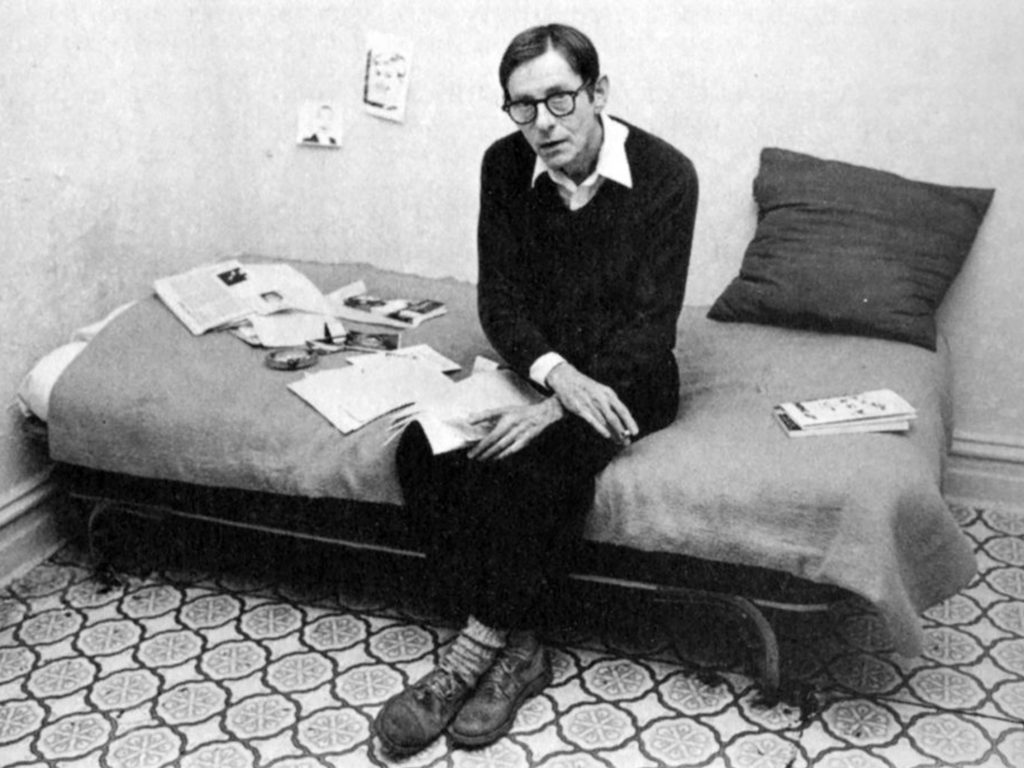

For decades, Straight to Hell has attracted a substantial audience while the guardians of official culture have generally remained oblivious. Why this should be the case has a lot to do with the unique path Boyd took in life. He transgressed a number of class boundaries and thereby gained the insights that made his achievement possible. Boyd was born into the Midwestern middle class, educated with the East Coast elite, and worked among New York’s professional upper-middle class; in his generation, there was nothing extraordinary about that. Then he had a fall in status, relying on welfare and living in a single room. It was then that his life truly began, and he became the sort of man who deserves a biography. He found a way to thrive in circumstances that would have defeated most people. Boyd used to joke that Straight to Hell was the only gay sex magazine funded by the United States Government because he used welfare money to pay his printing bills. Boyd McDonald’s work would have harassed the pleasant slumbers of respectable readers had he ever reached them. He did not, and as a result, comfort, complacency, and mainstream recognition eluded him.

William E. Jones has made the films Massillon (1991) and Finished (1997), which won a Los Angeles Film Critics Association award, the documentary Is It Really So Strange? (2004), and many videos including The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography(1998). His work was included in the 1993 and 2008 Whitney Biennials, and he has had retrospectives at Tate Modern (2005), Anthology Film Archives (2010), and the Austrian Film Museum (2011). His books include “Killed”: Rejected Images of the Farm Security Administration (2010), Halsted Plays Himself (2011), Between Artists: Thom Andersen and William E. Jones (2013), Imitation of Christ, named one of the best photo books of 2013 by Time magazine, and Flesh and the Cosmos (2014). He lives in Los Angeles.

This post may contain affiliate links.