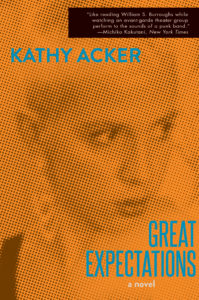

Chapter one: “PLAGIARISM”. Charles Dickens’ Pip has just become Peter when Kathy Acker’s Great Expectations (1982), a serialized collage of a book that steals from and destroys Dickens’ 1861 original, begins. “I RECALL MY CHILDHOOD”: Pip has lost his parents. Peter, too, has lost his parents, but not in the way we were once familiar: his mother has killed herself, his mother’s mother has also died, and he has never met his father who fled before Peter was born. In Acker’s version, the paternal h/role left in the absent father’s wake is filled over and over again by men who violate, manipulate and abandon women, including Acker’s gender-shifting narrator. These figural fatherly substitutions — many of whom we see alive and well today as politicians, societal leaders, friends, faux allies, etc., — repeatedly kill the mother (blood-line and symbolic). “The woman replaced him and replaced him (the form of this novel) and ultimately that killed the mother. Repetitive male fear kills women in Kathy’s novel. Man can’t bear the facts of life and women are stuck with it. Women are it. The mother passes the knowledge on to the daughter. And all of it happens in the body,” writes Eileen Myles in the introduction to Grove Atlantic’s reissue of Great Expectations, published March 2019. Kathy Acker had a great sense of humor. She knew how to parody not only Dickens but the purest of pains, often by writing it as viscerally as possible, i.e., through the body.

The Mother Wound and its inheritance is a reoccurring monster in Acker’s novels: ripping apart the flesh, lives, and memories of her protagonists. Abandonment is the trigger, being forgotten, left out, erased, unmoored. And inheritance is the key to its cyclicality. Shame, attenuation, self-sacrifice, emotional (self-)suppression, physical (self-)suppression, service as a replacement for care — these things are taught, passed on and internalized from mother to daughter and so on. But as Acker writes in Great Expectations: “Before I was born, my mother hated me because my father left her (because she got pregnant?)” We learn the Mother Wound is not matriarchal, far from it, and is instead inseparable from patriarchal systems of ownership and its consequential oppressive expectations of female singularity (for to become mother is to become multiple). Acker’s Great Expectations is full of daughters trapped in a sticky web of pain and pleasure, love and hate, service and power, all confused about their desire for freedom. They are fucked by fathers who also fuck their mothers and sisters. They love their mothers. They hate their mothers. They are their mothers. They don’t want to become.

“This is the dream I have: I’m running away from men who are trying to damage me permanently. I love mommy . . . the young girl RECOVERED” (italics added)

(This feels like a punch in the gut. This feels like scrambling up an already crumbling wall, but doing it anyway.)

Whenever I read Kathy Acker I am reminded of Tiqqun’s life-changing book, Preliminary Materials For a Theory of the Young-Girl (translated by Ariana Reines and published by Semiotext(e) in 2012), in which the young-girl is posited as not so much a category of gendered youth, but as an existential state. In Great Expectations, the young-girl is Peter is Kathy Acker is a daughter is a mother is a wife is an orphan is O — from Pierre Guyotat’s sexually violent novel, Eden, Eden, Eden — is a sex worker is an author is a male artist is a female artist is a muse. The young-girl as a complex, porous, wanting, commodified, violated space is that which Acker built Great Expectations from/around/upon/within.

Whereas, for Charles Dickens, the ‘child’ was instead a perverse space of innocence birthed from privileged ideology and classism, then filled with romanticism and idealism. His child is a host for a story about the ascent to gentlemanly status, a way to role-play healing from trauma through the elevation of societal class. Pip personifies opportunist advancement, as well as the ability to side-step consequences or personal responsibility on account of his purported naiveté. He is a boy performing as man performing as boy (a-never-becoming). Whereas Acker’s child just wants to survive — to live. The young-girl, who shifts in age throughout the novel, is never truly granted the innocence of youth. For example, when she is a six-year-old the narrator is taken by her grandmother to a restaurant where she lifts her up “pink organdy skirt” to show the waiters her girdle:

She realizes that she is at the same time a little girl absolutely pure nothing wrong just what she wants, and this unnameable dirt thing . . . This identity does not exist . . . All the men she has don’t recognize her humanity.

Orphans are sex workers living in a “female terrorist house which is disguised as a girls’ school.” Soldiers rape young girls and murder babies. Money is not so much a product or producer of elitism and class, but a resource for survival and potential destruction. For Acker, to desire money and fame is moronic, irresistible, and necessary. And for the child in Acker’s story, money is as much a materialist burden (“I was no longer a person to a man, but an object, a full purse”) as it is an opportunity for freedom (“ . . . neatly folded the bills and stuffed them in your cleavage. / Your chains are disappearing.”). Both Acker’s and Dickens’ children want to transcend their current cultural, societal, sexual, temporal, or spatial situation by dismantling their bindings: a city, family, sexuality, money, a house, chains, marriage (law), art and, perhaps, language. However, unlike for Dickens’ Pip, money and materialism can never truly be separated from the young-girl’s body and identity, rendering her a possession and never the possessor.

Sure, Kathy Acker exploits the young-girl, but she also writes to honor her. To love her. To expose her robustness. To give her space. She questions her as image, as myth, as perfect, as a hole, and therefore less than human. She questions her paradoxical hyper- and in-visibility. Acker knows the young-girl. (Remember there are two “i”s in fiction.) A perpetual child, she is powerlessness. A female, she has power, although it is always relative. “THERE’S NO SUCH THING AS POWER AND POWERLESSNESS,” writes Acker. No such thing. She knows that in order to write about/for the young-girl she must write in a language which, as Acker once detailed in an essay, she can only come upon as she disappears — she must write through her incompleteness. In Great Expectations, Acker’s young girl does not exist. Her young girl is timeless and “Timelessness versus time.” She is boundless, travelling through time and dimensions, and therefore, for Acker, she becomes not only a state but a method for subversion. The young-girl is piratic, and this book was her methodological debut.

***

Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations is one of those stories that, over time, has cemented itself into the canon and curriculum and collective consciousness as ‘classic’. It is an old tale kept alive as fable and through fabulation, produced and protected by the masculine ego. Dickens’ Great Expectations is a singular example of the ‘high’ literature that has, throughout history, categorically excluded the experimental, the innovative, the anarchist, the crass, the subversive, the marginalized, BAME, LGBTQIA+, working class, and women writers from the canon. And since the becoming of the canonical is a collaboration of class and capital, for a book such as Dickens’ Great Expectations to be viable for cultural continuity (repetition and retelling) it must be produced via exclusivity while remaining generically pertinent (i.e. normative). It must, in a sense, become and exist within a literary vacuum. It circulates and circulates as a product of its time, as well as a continued transcendence of it: being re-read, re-published, re-told, re-made, as novel, as film, as academic study. Here, in a space devoid of meaning (and certainly devoid of contemporary cultural critique), time as contextual relevance becomes moot and these untouchable canonical books — or more importantly the ideologies they entomb — keep going round and round and. So, it is important to consider: Why bring a text back? Why return to — in particular the male canonical — texts of the past?

Great Expectations was the first of Kathy Acker’s experimental novels to have been written using the “cut-up” method. Largely suggested as William Burroughs-borrowed or positioned firmly in the camps of postmodernism and poststructuralism, Acker’s cutting-up of old stories and texts as literary method has been criticized as plagiarism and, at worst, critiqued as phallic reproduction via intentionality. As Hèléne Cixous wrote in her 1976 essay The Laugh of the Medusa, the purpose of écriture féminine or “women’s writing” is not to “appropriate [man’s] instruments, their concepts, their places, or to begrudge them their position of mastery,” but to create a new style of writing that carves out textual and affective space for marginalized subjectivities and bodies. And indeed, Acker did deliberately return to and steal from phallogocentric history in order write through (and against) displacement and innovation. However, as with Great Expectations, none of this was for mere representationalism. Nor was it ever a case of retelling or rewriting Dickens’ story through a female gaze or even a female body. “If you want to understand an event, always increase its (your perceptive) complexity,” writes Acker. She was not trying to understand Dickens, nor the story itself, but the socio-political and cultural underpinnings that allowed it to materialize and remain on the pedestal of ‘high’ literature for, at her time of writing, over a century. As well as her own history, subjectivity, body, and life.

Great Expectations was Acker’s starting point in literary destruction as method, but not for disruption, nor deconstruction, nor appropriation. Instead it was for complete annihilation — in order to “see” as a young-girl as a pirate. As Acker suggested: “The only way you can get the real self is to rip someone off.” It was plagiarism as piracy in its most practical form: to break into and apart copyright and literary law. She ripped Dickens’ tale apart and from the wreckage wrote something wild and alive. It was supposed to fuck up the system and, as Eileen Myles writes in their introduction, it was “the book in which she did everything for the first time, it’s serialized unto itself. It’s bits and pieces, it’s variegated stuff. Versions of slime and what fights it too. A rescue mission.” The methods in which Acker wrote and distributed Great Expectations was fragmentary, parts looped together with splitting red ribbon. For that reason, structurally, the book is genius.

It begins with childhood recollections, switching back and forth between Christmas Eve and Day 1978 and war scenes. It is pure terror, sex, violence, dog-toothed desire, salivating hunger, blood red, quickly turning to soft tears, cold surfaces, and nostalgic longing. Turn the page: chapters reveal themselves like Russian dolls. Prose is spliced with monologues, letters, lists, erratic dialogue, and teleplay. Sentences slam into one another, or they swim, drip, dribble; commas lace scenes together, overlapping and becoming; colons layer and layer dreams upon memory upon the real, or they replace periods, suggesting phantasmic continuation. In some places, punctuation is absent all together and sentences hang on the precipice, leaving a haunted space heavy with meaning. The narrator shifts continuously. Characters swim in and out, some return and some do not, some we know — or we think we know — and some we do not. For example, there are comically titled missives to critics Sylvére Lotringer and Susan Sontag, David, who is perhaps poet David Antin, and Peter, our narrator, but also maybe, theorist Peter Wollen.

In a sub-chapter titled, The First Days of Romance, Acker jumps between writings of the internal claustrophobia of young-girl, Sarah Ashington — who has recently inherited her dead father’s wealth and is shackled to a brute of a man, Clifford (Clyfford!) Still — and philosophical reflections on beauty and sensuousness (“Oh, for a Life of Sensations rather than Thoughts!”), uncredited excerpts of John Keats’ poetry, meta writings to the author (she and he), and then, we’re on a pirate ship. It is a heartbreaking parody and critique of romanticism, which remains, at all times, acutely self-aware. Acker does this throughout the book. Skating across time and memory, sailing between different characters and stories and worlds, in order to get inside and see all things: romanticism, literature and its establishment, sex work, classical art, contemporary art society, money, class, gender, marriage, fame, (roman) myth, and history. Each section is a swirling constellation of stories that have no boundaries or walls, although they are full of mirrors: self-reflective, self-aware, self-critical, self-referential. Meta and always moving. Acker writes:

There is just moving and there are different ways of moving. Or: there is moving all over at the same time and there is moving linearly. If everything is moving-all-over-the-place-no-time, anything is everything.

Great Expectations is a jenga-style building block collection of Acker’s thoughts which coagulate as shocking fictions that, while always situated, displace time and call it into question repeatedly. Through this book, Kathy Acker offers a historical structure and writing methodology for going/looking/feeling backward, or as professor Elizabeth Freeman proposes in her 2012 book, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories, for returning to trauma “for the purpose of organizing it into an experience.” Within Great Expectations, Acker provides various frameworks of feeling which allow marginalized people and survivors to go back and make sense of their pasts. One way this is done is through failure.

Firstly, Kathy Acker’s Great Expectations fails to be what it once was. Secondly, it fails to align with normative literary codes. And, thirdly, at the time Acker was writing and distributing this book, it failed to disrupt “politely.” Acker wasn’t concerned with being a “good” daughter of feminism nor literature, and this book, through its failure to adhere to acceptable codes of resistance with regard to women’s bodies, sex, sexuality, gender, and identity, muddied the waters of what constituted as normative or as desired liberation. Acker’s refusals to conform, in text and through body, creates what Freeman suggests as an “asynchrony, or time out of joint.” By negating linearity, by keeping moving-all-over-the-place-no-time, Acker’s writing opens up chasms in time, allowing the past and what has been kept hidden to make itself known in the present. Through these chasms, Acker and the reader are able to look back at the scrutinizing, surveilling, objectifying, and oppressive gaze through which certain experiences were once formed. Great Expectations, in its fragmentary state of partiality, is a book about the young-girl’s unbecoming and undoing, as much as it is about her becoming. It truly is a book where anything (and every thing) is everything. Every page forces the reader to stop, to think, to see, or it grabs your face, turns and whispers “jump.”

***

And jump Kathy Acker did. She continues to today, over twenty years after her death at age 50 in 1997. This reissue is proof of that. Since Chris Kraus’ biography, After Kathy Acker, was published in 2015, Acker keeps reappearing. Her work is being re-published and her life written about or exhibited. I was wary of this at first. The hurried timing of it all seemed uncomfortably opportunist: the programmed after-life of (After) Kathy Acker. Although, now, I see how this contemporary return to Acker may be similar to how Acker herself returned to those who lived and wrote before her: as something unfinished. In a review of the 2018 exhibition, Kathy Acker: Get Rid of Meaning, at Badischer Kunstverein in Germany, McKenzie Wark suggests, “She wrote for the radical, queer, trans, precarious reader to come.” Acker went back(ward) in order to reach further, to go further (forward), that’s why we feel her so intensely now. But returning and retelling is precarious business. And of course Acker knew this.

When Kathy Acker’s Great Expectations was originally published in 1982, it caused a chip in time. And every reissue since has caused another. For her, going back(ward) was about breaking stuff apart. It was about interrupting chrononormative methods of recounting history. It was about understanding, feeling, perceiving, creating, and writing the self into existence by critically situating herself within that which displaced and foreclosed her. It was (to borrow from R.D. Laing’s Knots) “to eat and to be eaten / to have the outside inside and to be / inside the outside.” For Acker, Great Expectations was not about becoming or exorcising Dickens’ ghosts, but it was about summoning and communing with them, making a mess with their spectral goo. That is why we must not only return to Acker’s work, but we must return to it as Acker herself would have done so: by dragging it through time, identifying its movements, analyzing the context of its productive practices, critiquing our relationship to it and its relationship to all things that equate with Time. Like with all ghosts, we must be tender with Acker’s literary archive. We must pay attention, listen and avoid carelessness through retellings at all costs. Eileen Myles is right: “This book is a warning.”

Mollie Elizabeth Pyne is a freelance writer and Masters student at Goldsmiths, University of London, specializing in feminist and queer theory, body studies, and literature. They are currently based in Devon. Sporadically tweets @bittter0cean.

This post may contain affiliate links.