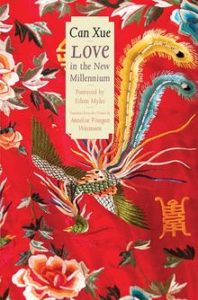

[Yale University Press, 2018]

[Yale University Press, 2018]

Tr. from the Chinese by Annelise Finegan Wasmoen

For this novel, “new millennium” doesn’t necessarily mean the year 2000, the time that we’re in now, or any knowable set of thousands. Time operates a little differently, as it tends to do in most of Can Xue’s work. The laws of the universe, space, and time appear ordinary, but the atmosphere is unsettled: there’s an inkling that something’s off, and sometimes the characters notice it too. As for “love,” everyone is either in love or in search for love, but interpretations abound. Declarations of love are surprising; relationships come and go; mysterious doppelgangers and messengers flit about caves, prison cells, trains.

I always hesitate when recommending Can Xue for these reasons. I am an emphatic fan who, for about a year after the release of Frontier, found a way to insert it into most conversations. But my hesitation lies in the simple worry that the recipients of my recommendation won’t like it. In an early review of Frontier, a reader expressed joy and dread that the novel felt like it was getting longer — that it wouldn’t end. With each page, the reader made little “progress,” or that’s how she gauged her experience. (The fact that I can’t locate this review now is fitting.) This is because Frontier and Love in the New Millenium operate in worlds of suspended time. Plot isn’t grounding us here. The narratives shift between chapters. Events and sentences repeat. That buoyancy, though, is mimetic of the lives and spaces the novels contain. In the Foreword, “Inside Can Xue,” Eileen Myles better captures what I mean:

Part of the difficulty of reading Love is I couldn’t stop tweeting passages. To be a reader was to become a trailer, or to become an actor too. It’s irresistible, the way one enters this laughable shifting no time that everyone inside is talking about like the weather. It’s also very boring, as a plotless book is. A circling non-building narrative gets tiring. What’s the pleasure then? Humor and surprise. It’s a frankly poetic existence. Plus my reader’s sense of awe grew continually at the endless refillability of the thing. The book is a vase, it’s a form.

Many passages enact the humor and surprise Myles finds. In one, A Si, a woman who has just been injured by a machine in a cotton mill, wakes up to find her ex-boyfriend, Trailblazer, sitting on her windowsill. He says,

“Once I heard about your injury, all the affection I had for you came back to life. Do you still remember those times we spent in the factory park? You’re not badly hurt?”

A Si dully observed the Trailblazer’s handsome face and felt the same seduction as before. Yet this temptation seemed to be separated from her by a membrane, such that at this moment it no longer touched her. He had so much life in him! Had he come to test her? A Si lowered her head and started giggling.

The Trailblazer pounced on her. A Si snatched a pair of scissors from the table and stabbed the man in the arm.

“You’re really extreme.” He retreated through the door, saying, “A Si, I love you even more!”

“Love, what’s love? My door is unlocked. You can visit any time.”

Can Xue’s pacing here is quite extraordinary. The initial interaction is boring and slow: Despite his name, the ex-boyfriend’s comments are banal. A Si looks on “dully,” and she’s closed off by a “membrane.” But then, action. She giggles, he pounces, she stabs. Then he’s in love with her again and flies out the door. Her cryptic response is left with no further explanation as the interaction ends there, with a neighbor now entering the apartment and commenting on A Si’s head wound.

Zooming out, this is what we do get of plot in Love: a group of people who live in the same city are entangled in relationships and occupations. They change partners and jobs. They run into each other in the street. The rotating cast, which deemphasizes the centrality of one character over the other, includes Cuilan, her lover Wei Bo, the trio A Si, Long Sixiang, and Jin Zhu (who meet Cuilan at the spa and have varying relationships with Wei Bo), Wei Bo’s wife Xiao Yuan (who is obsessed with clocks), and the antique dealer, Mr. You.

Aside from Mr. You, each of the other major characters experiences or demands a change in vocation, and this is pretty significant for identifying what’s going in the novel: Wei Bo works at a soap factory and has a few other part time jobs, but early in the novel, he gets himself admitted to a prison. Xiao Yuan travels from the city to consult on the “operations” of school districts, and she later becomes a teacher in a rural village. Cuilan works at an “instruments and gauges” factory and the other women at a cotton mill or a cement mill. They leave their factory posts to work at a spa, meaning sex work, even though they each feel “too old” to do so.

In present day China, economic development is grounded in rapid industrialization. (My favorite article on this is this one where the amount of cement used in China between 2011 and 2013 is represented as a giant cube looming over downtown Chicago.) Scores are migrating away from villages to cities. An example of this trend in novel form is Northern Girls by Sheng Keyi. There, young women flock from the country to factories in the city and engage in sex work along the way. Love, to me, reads like a revision of Northern Girls combined with Can Xue’s Frontier (the one I can’t stop talking about). Frontier is set a mountain village, Pebble Town, where one of the central characters has decided to remain after her parents move to the city. The country landscape in Frontier is pure Can Xue: part fairy tale and part mystery with little resolution. This is also true of Love, especially when we follow Xiao Yuan to Nest County which feels a lot like Pebble Town. Add to this the fast absurdist dialogue from Can Xue’s Yellow Mud Street and we might assemble something like Love in the New Millennium.

Love’s characters’ vocational and relationship shifts are significant when considering “the new millennium.” The millennium reads not necessarily as a change in years, but as an edge or threshold the characters are moving through. This is especially true for the women in the novel. They primarily hold industrial jobs and leave them because, in one example, the cotton factory made them sick. Sex work is more appealing: they lounge at the spa, meet wealthy men, manage their own schedules. In Nest County, Xiao Yuan finds fairy-like children and her doctor-crush combs mountainsides for Chinese medicinal herbs.

Looking to the past, characters continually refer to, ask about, or physically return to their rural hometowns. In a twist on that theme, Long Sixiang (whose name means “homesick”) finds herself returning to a place called Mandarin Duck Suites to be with a man who was born there. Caves that housed families are beneath the suites, and manifold rooms branch off each other. She fails to count them. Nevertheless, the sounds from the caves, the echoes of someone else’s history, call her back–to this location, to someone else’s history–over and over. She’s in love neither with the man nor the place, though. In fact, I’m not sure what Long Sixiang feels at all. Even as the women change position, at work or in physical space, they seem to always remain in this threshold, like they’re suspended in “the millennium.”

I keep thinking of a scene where Cuilan is trying to visit Wei Bo in prison, and she gets a ride from a man pulling a cart:

The detention center never vanished from her field of vision, nor did the enormous tree. The cart had traveled quite far and turned twice, yet she still saw the building. It was so clear even the sheets drying in the sun could be seen distinctly. She thought something was not right. The old man kept moving forward without rushing or slowing down. Cuilan smelled the sweat spreading through his undershirt. This man reminded her of her father. Her father had rescued her from danger on several occasions. Her teeth still hurt, and the cart was uncomfortable. The worst was that she kept seeing the building and that tree. Could she not leave this magic circle? The thought made her even more confused.

She is moving through memory and her senses, but the cart is going nowhere. It troubles her that she can see this. What is the magic circle? Memory? The endlessness of the trip? Her relationship with Wei Bo? The last story from Can Xue’s Dialogues in Paradise echoes here:

Do you know what happened? Do you know what happened?

I have been searching. I may find something again. (This is a vast world.) It is an unbreakable wicked circle.

A wicked circle to a magic circle. Myles calls Love endlessly refillable: “book is a vase, it’s a form.” This novel is bound, but refillable. Without narrative restraint (like both love and time?), it can’t really end.

Kelly Krumrie is a PhD student in Creative Writing / Literature at the University of Denver. Prose is forthcoming from or appears in Black Warrior Review, SHARKPACKAnnual, Sleepingfish, Shirley Magazine, Your Impossible Voice, and others. She is currently the translations editor at Denver Quarterly. Links to her work can be found at kellykrumrie.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.