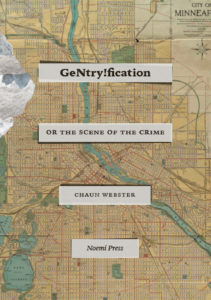

What I noticed right away about Chaun Webster’s book GeNtry!fication: Or, the Scene of the Crime is how he acknowledges the full span of the Black literary canon which includes, not only writers we might expect to see, such as Audre Lorde, James Baldwin, Dionne Brand, Amiri Baraka, bell hooks, Sylvia Winter, Kevin Young, and Toni Morrison, but also history, contemporary music, pedagogy, and radical self-work as tools to approach Black study. GeNtry!fication is an academic and experimental work that does not make excuses or apologies about where it is coming from. Origins are valid. The language of those origins is valid. The Black canon is valid. This experience is valid. Webster initiates his readers by example in a process that aims to not only root out oppressive ideologies, but to provide tools for Black study, and for the creation of safe places where that study can occur.

Webster treats the Black canon in such a way that it is not separate from himself. He does not place that canon or its participants on a pedestal, as so many of us do. Instead, he earns his way, acknowledging the lineage and his contemporaries who have done/are “doing the hard work of naming the crime and tearing this whole bidness down . . . seeing through the rubble.” He does this every step of the way, and he interacts with it in real time. Then he extends that interaction towards his immediate community and also towards us. We are part of this. There is work to do. We’re not just musing on possibilities here. We’re not just nodding or shaking our heads in agreement and/or disbelief and saying, “Damn, what a shame” from the sidelines. We are learning how to “reckon with the din,” to find some way to not only understand our placement in regards to Blackness, but to find freedom from the ideologies that impose on the Black body and hence Black spaces which are constantly being erased. Webster asks, “How might we go about mapping what is not there, what is missing, and enter the vacated space?” This question is all of ours now, and the book offers some tools and ways to think about the problem.

While GeNtry!fication, is a performative book, seemingly playfully made, Webster is not messing around. We know this from the book’s first pages. The crime is promptly named. Black bodies and Black spaces have been robbed of their authority. Voices such as those named above, Langston Hughes, Tribe Called Quest, Douglas Kearney, Fred Moten, Black sons and daughters, mothers, fathers and ancestors, have been telling us, showing us, and so has our DNA. “The smallest cell remembers (NourbeSe Phillip).”

Each page of this book feels like a surprise. Text and fonts merge and sift through the page, and illustrate ideas by way of their placement. For example, in “this is not a black: an abstraction on a nonessential thing,” there are two boxes, which illustrate a black and white binary. Inside of a white box reads “this is not a,” and inside the next box, where we not only see the expected word “black,” we see enough overlapping instances of the word “black” that the word becomes for the most part illegible. Suddenly, the word has created a safe space for Blackness, a sort of in-between space. “this is not a black” now means another thing. It has become a reclamation in lieu of the idea that “maybe black is not a home or a country . . . but the imperfect signifier we carry on our way.”

“Din is discourse” (Glissant), Chaun Webster reminds. One must go the way of the incessant and piercing HOWL because the alternative is a reality that seems impossible to break. The howl combats against history’s tendency to silence. The howling must become louder than the silence. It prevents a long line of social injustices that are still happening from being swept under the rug. And as we all know, history tends to sweeten, twist, and sweep social injustices under the rug, even when we see them happening right in front of our eyes. So, stand witness. HOWL!

Webster doesn’t solely tell us to make a loud noise. While it is a powerful and necessary act, making a loud sound is but one small part of what needs to be done. We must also remember (“say their names!”) and study, not only history and the canon, but the spaces in which we live. We must also study ourselves. Look around. Look inside. Class is always in session.

We see a defiance of accepted conventions. Webster treats these acts of resistance as a necessary response to the stultifying feeling that the ideology we are facing seems inescapable. The ideology demands that we speak inside the realms of its patterns and use whatever tools it provides. But these patterns and tools are made to absorb and to entrap, not to assist anyone in their particular experiences. There is a feeling that the ideology so entraps, a certain kind of transcendence is required, or at the very least a very deft sidestep, a movement towards some in-between place in which Black people can exist without being detected. To be detected is to be stolen, and to be relegated to a space of stasis that only serves the ideology. In a sense, transcendence means that we must become ghosts, we must “speak our names in secret” (and howl like proper haunts). This movement towards illegibility creates a space that is separate and uncommodifiable, and it breaks from the inescapable cycle of theft that is so well outed in these pages.

A performative example of this side-stepping in the text occurs when we see one small, almost imperceptible deviation on a page on which “black” is patterned repeatedly in tiny letters. It reads: “this is just my way of saying I don’t care to be legible.” The passage is so embedded that it could be missed. The sentiment is an echo of Dionne Brand’s statement “I don’t want no fucking country, here or there and all the way back, I don’t like it, none of it, easy as that.” To be tied to a country is to be tied to the ideology it has instated. And to be tied to that ideology as a Black person, is to be stolen.

The illegibility that Webster points to in his book does not quite mean invisibility. Black people and Black communities still exist. The line mentioned above seems to point to the question: How can we create safe places in which we feel wholly ourselves, a place in which we have the authority and freedom to be our own, to own our bodies, to own our experiences and commune with each other on our own terms? Webster reminds us via Kameelah Rasheed that in past social movements, “People covertly published things, and covertly educated people, and covertly got training.” These actions are “ . . . not so much hiding, but strategic opaqueness — refusing to be legible.” It is a way for folks to keep their own. Safe spaces have to be reclaimed. Safe spaces have to be created in whatever capacity so that Black communities not only survive, but thrive and grow. And no matter what, Black communities will thrive, persist, and grow, even if “The future has been around so long it is now the past.”

Movement towards the creation of safe spaces includes taking action towards reclamation. Redefining the terms that pin people to the ideology’s agendas is necessary. It is survival. One of many notable instances of reclamation that occurs in GeNtry!fication is when Webster breaks down the letter “N.” In “N in molecular type” he notes that “N is formed by two binaries that have overlapped and bonded with the W imagination.” He literally breaks the N apart on the page and analyzes it. Later, the “N” is reclaimed in the following realization/summation:

1. black

2. is

3. a

4. destination

5. N

6. perpetual

7. exile.

There is incredible power in that realization (“maybe black is not a home or a country . . . but the imperfect signifier we carry on our way”). The realization provides a tool that folks can carry. It is an entrance point into the way forward. It provides a new view which directs us towards an answer we cannot yet name but feel now exists.

GeNtry!fication isn’t just a book of poetry that dances around a question. It is an experimental essay that delves deep and also inducts its readers into the process by asking difficult questions that the author himself is seeking. The book carries such questions from the beginning to its close, and Webster has given us, his community of readers, plenty of entrance points into the conversation. Every step of the way, I felt the invitation for each of us to contribute our piece of the proverbial puzzle, to do our homework, to continue on in self-study in regards to our placement inside of current oppressive ideologies and their treatment and definition of Blackness, and to speak loudly of our experiences. Webster gives a long list of essential reading that not only informs, but can release a body from the binds of falling victim to the seemingly inescapable crime. Knowledge is power. Truly. Webster has also made a lot of connections already, building on the canon, and drawing lines that each of us can follow. It’s our job to continue forth and to walk with the Black canon in a quest to tear the ideologies down.

Webster is an apt guide who doesn’t just talk at us. He doesn’t hold his process to his chest. He doesn’t lord it over our heads. He doesn’t keep secrets. He lays it all out and leads by example by the way he treats the text. One moment that comes to mind is in “forbidDIN,” where Webster shows us in words that overlap enough to create a black space on the page just how loud our howling needs to be (HOWL child! HOWL!) so that we can covertly live and do the work that needs to be done.

In my opinion, this book goes alongside so many other manuals which work towards similar aims such as Angela Davis’ Freedom is a Constant Struggle, Martin Luther King’s Why We Can’t Wait, and bell hooks’ Where We Stand. In my mind, I see Chaun Webster, and also hopefully us, marching within the troops of voices who make up the necessarily loudening Black canon. HOWL!

Tameca L Coleman is a singer, writer, massage therapist, itinerant nerd and point and shoot tourist in their own town. Tameca has published work in many genres, and has also performed and recorded music with many different bands. She doodles sometimes and likes weird music and dancebreaks. For more information about their work, follow @sireneatspoetry.

This post may contain affiliate links.