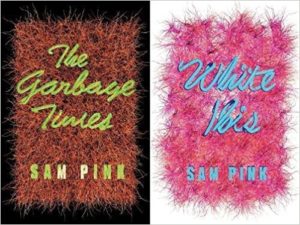

Me and a few high school chums were that commiserating type who shared a roster of sorry literary paronomasia, biting our thumbs at each other in the hallway and close reading every composition as: “Lacks character development!” This was even funnier if what fell under our ironically detached scope was a non-narrative poem, or a piece of somebody’s lunch. An encounter with Sam Pink’s sequential novellas The Garbage Times and White Ibis might stump many a smartass attempting to cite insufficiency of character. The author embraced a hellish way of life, folding it into a junkyard exacta of layering, returning maniacally gritty, far beyond anyone tickled by Bukowski in their teens. Think back to those stark depression era novels about riding the rails: neglected masterpieces such as Edward Newhouse’s You Can’t Sleep Here, Edward Anderson’s Hungry Men, Robert Cantwell’s Laugh and Lie Down, lost somewhere between the anti-Dickensian orphanage of Edward Dahlberg’s Bottom Dogs and a demented version of the self-help humanitarian mindset candidly but naïvely professed in Vachel Lindsay’s A Handy Guide for Beggars (done with much more hyperbolic irony in Pink – recently deceased poet Mark Baumer would be this generation’s genuine Lindsay) – in effect it’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They in a funnier, sustained alt lit sentegraph.

Pink successfully distinguished himself from the technical influence of Tao Lin’s aphoristic drone by taking the refactored Lishian minimalist sentence and exaggerating it like one of Mike Tyson’s numbered combos: a left hook transformed into an uppercut, starting with the body, terminating the head. Effaced within a voice bracketing around its own circumstance, this excursion is undergone by a street participant fully capable of mocking and being mocked by fate, taking it on the chin, so to speak, like the taxes diced from your already curt minimum wage paycheck (made relevant as that option increasingly becomes this generation’s best bet). Secondly, Pink’s talent divorces him from other (further malevolent) contemporary associations. For instance, Ben Kerns includes him in an article as part of a “New Violence” trinity alongside avant garde malcontents Blake Butler and Sean Kilpatrick. Pink demonstrates much healthier maturation by acknowledging a sardonic smirk: teeth proven, available, but never lodged willy-nilly into the thesaurus. Once you’ve aged even a little, anger often changes from an irrational bark to an insight. To allay the reader with a communicatively phatic appeal, practicing your voice sans compromise works a million times better than the spastic provocation of every available cultural anxiety. The psychotic culture of oneself can be pruned with something sharper than a cannon.

These juxtaposed novellas are about how any benumbed existence, any circumstantial grind, can backfire and produce a mind, despite the will of our petty culture, despite the domestication every act of love unwittingly employs. As the protagonist is transported between states cold and hot, from The Garbage Times to White Ibis, sport-fucked on the samurai sword of being hired anywhere, a splenetic ecstasy discloses itself as the eighteen-hour work day is traded for another uniform you still owe on (the lucrative idea that only pussies opine on such matters, even to themselves, even to the revolt of a page – maybe take a selfie holding some slogan-scribbled placard for the prettier reward of a like) – an enlightenment which can only provoke genius, once the bacterial swarm Edward Bunker’s toothbrush spot-cleaned into immortality skunks the whole concept. Notice, in this short excerpt, the panoply morphing from: ironic, anachronistic idiom to the grammar of the modern sentegraph, underlined by the autocorrecting despondency of some inverse self-help mantras made popular online:

Loop high that bag young man.

And be proud.

Comforted that you’re at least still needed and able.

Comforted that garbage always smells the same.

Like a promise.

Like an only friend.

Pink updated the palate (he’s an excellent painter as well), smearing a faddish alt chroma into his own idiosyncratically hard boiled detachment forged under threat of violence and in place of numbness, or with less novocaine piped in. Rather than the ubiquitous farces deeming everything slightly effortful too melodramatic (or lacking x,y,z – a single supposed flaw applied across the complex entirety of an art form for absurd, comedic impact), Pink advances a premise by inflating life on its own melodrama (his idiomatic transcripts of voices developing, then imbuing character in locations as diverse as a Chicago ghetto and rural Florida), a welcome and necessary deviation. These books conjoin readers with a hilarity freed forthright from the widespread gutter of any discouraging affiliations.

Alfred Wichly has published writing in Hobart and is tentatively assembling transcripts of a public access interview show he produced, some years back, which focused on writers. He lives in Detroit.

This post may contain affiliate links.