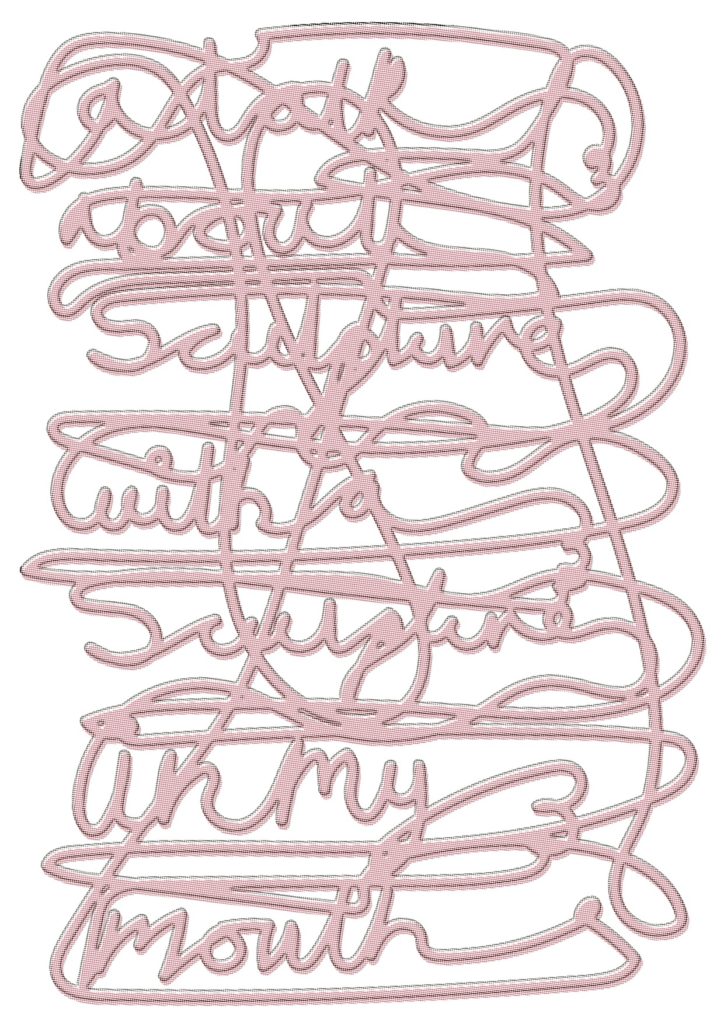

Luke McCreadie, “A talk about sculpture, with a sculpture in my mouth,” 2017, Riso print on paper

This essay first appeared in the Full Stop Quarterly, Issue #6. To help us continue to pay our writers, please consider subscribing.

The potential of English-language poetry in Hong Kong

Louise Ho (b. 1943), known for her innovative use of language and poetic commentary on Hong Kong, is one of the most celebrated poets writing in English in the city. In her foreword to the anthology City Voices: Hong Kong Writing in English, 1945 to the Present (2003), Ho laments:

Those of us writing in the English language in Hong Kong would know the feeling of isolation, perhaps of functioning in a void. There is no English-language literary community from which to draw some kind of affinity or against which to react. There is insufficient writing in English here for a critical mass to have formed. The literary traditions that do exist in Hong Kong are, obviously, those of the Chinese language.

More than a decade on, Ho’s rather gloomy take on the state of English language writing in Hong Kong to a large extent still holds true, despite the fact there have been obvious improvements, into which I will go in more detail below. Cantonese Chinese remains the preeminent language in the city in terms of exchange of information and creative expression and will no doubt continue to be so. English is a minority language in this respect. On the other hand, Mandarin, which is also Chinese, but a form of Chinese used more on the mainland, is increasingly visible and important in the city. English failed to take widespread root in people’s imagination during British colonial rule when it was visible in every aspect of the functioning of the territory. It would thus be naïve to dream of its miraculous rise now, after the 1997 handover, when Hong Kong’s sovereignty was returned to the People’s Republic of China. Mandarin, not English, seems to be increasingly the true ‘colonizing’ language in the city.

But I do not think that those writing in English in Hong Kong necessarily feel a strong sense of ‘isolation’ now. There are a number of English-language writers’ groups in the city (some of them have formed before the handover): the Hong Kong Writers Circle (HKWC), Poetry OutLoud, Peel Street Poetry, Hong Kong Women in Publishing Society (WiPS), to name a few. Members of these groups meet regularly, and some of these collectives, such as the HKWC and WiPS, produce thoughtful and carefully curated print publications periodically. Members of all these groups tend to be a mixture of expatriates and educated local writers. The Hong Kong Book Fair (held in the city in July every year), the Hong Kong International Literary Festival (held in November) and the Kubrick Reading Series and Ragged Claws—both have events throughout the year—also feature English-language writings and writers. We can certainly no longer say that ‘[t]here is no English-language literary community from which to draw some kind of affinity or against which to react’. One just has to go out, be receptive, join a group, and meet and mingle with other like-minded people.

This ‘community’, however, is very small, and in some cases ephemeral as members come and go. Some of them leave the city—Hong Kong but a transient home; and some move on to focus on other interests and priorities in life—creative writing but a temporary solace. If the general English-language community is small, the English-language poetry community is even smaller: a minority within a minority. Leung Ping-Kwan (1949–2013), the late great Hong Kong poet, shared his thought on the English language in an interview (1992):

I think growing up in Hong Kong has put a particular psychological block on us in the use of English. It has become in this society a means of evaluation, a measure of one’s social or economic status, a source of snobbery or mockery and so on, rather than a means of communication.

This is still the case today. The education system as a whole is not conducive for students to acquire the English language beyond practical uses. And there are few truly home-grown poets—born and bred in the city—who eventually go on to publish full-length English-language collections or find success in the international scene, even though there are several publishing houses in Hong Kong that feature English poetry in their catalogue—Chameleon Press and Proverse Hong Kong being two examples. Measuring one’s poetic achievement through the lens of Western recognition is perhaps neither desirable nor entirely relevant. But it still serves as a means of evaluating a poet’s output and the commensurability and reception of his or her work in a different cultural environment. With all this in mind, it is no wonder that Nicholas Wong’s winning of the 28th Lambda Literary Award in the category of Gay Poetry for his collection entitled Crevasse (Kaya Press) became a local media sensation in 2016, just as in 2008 when Arthur Leung was named a winner of the Edwin Morgan International Poetry Competition at the Edinburgh Book Festival in Scotland with his poem “What the Pig Ma Ma Says.” One hopes that all this intense yet sporadic attention for Hong Kong poetry from the larger society can be sustained and be not always anchored in external appreciation.

While there are not many home-grown poets writing in English publishing books (one thinks of Kit Fan, Louise Ho, Agnes Lam, Elbert SP Lee, Wawa, Jennifer Wong, Nicholas Wong, etc.), Hong Kong-based poets of foreign origin fare generally well. In recent years, a number of them have successfully launched new collections published either locally or abroad—and indeed some of them would be offended if they were not considered to be ‘Hong Kong poets’: Martin Alexander, Andrew Barker, Gillian Bickley, Celia Classe, Andrew S. Guthrie, Henrik Hoeg, Viki Holmes, Akin Jeje, Timothy Kaiser, Birgit Bunzel Linder, David McKirdy, Mary-Jane Newton, Collier Nogues, Jason S Polley, Vaughan Rapatahana, Kate Rogers, James Shea and Eddie Tay, to name some of them, adding to the vibrancy and diversity of the writing scene in the metropolis as well as hinting at the beginning of a ‘critical mass’. They write about the city, identity, personal stories, and eternal themes such as love, life, and family. Still, for someone like me who loves the city and who has hopes for its literary potential, this is not nearly enough.

I began this short piece by quoting Louise Ho and suggested that currently in Hong Kong the English-language poetry scene is not really much better than that in Ho’s appraisal. But I do believe that, for all the constraints—political, linguistic, educational, economical—it is possible for us to do better, if more is done by those who can effect change. Having literature in general and poetry more specifically as a staple subject in schools, having poets reach out to potential budding writers and nurturing them, ensuring that students who study creative writing at local universities get sufficient support for their subsequent writing career, urging the government to invest more in cultivating its citizens’ literary and creative expression, fostering a closer connection between writers who write in Chinese and those who write in English, and continuing the support of local writers’ groups, publishers, journals (such as Cha: An Asian Literary Journal and Yuan Yang) and organizations (such as PEN Hong Kong, relaunched in 2016)—all these help sustain the life of English-language poetry in the city, instead of letting it die.

Indeed, there has been a growing recognition of and interest in English-language poetry in the city. 2015 was an important year for Hong Kong poetry on the international scene, for example, with two Hong Kong poets—Nicholas Wong and Sarah Howe (born in Hong Kong and moved to the UK at a young age)—winning important awards. As mentioned above, Wong won the Lambda Literary Award for his second collection, Crevasse, while Howe won the TS Eliot Prize for her debut collection, Loop of Jade (Vintage Books). Wong’s and Howe’s achievements speak to an increasing global interest in Hong Kong poetry and the city at this particular juncture in history, when Hong Kong is in political and cultural transition between a past as British colony and a present as Special Administrative Region in globally powerful China. It is opportune—indeed, there is urgent need—to make sure that English-language poetry continues to flourish in Hong Kong.

Tammy Lai-Ming Ho is Assistant Professor in the Department of English Language and Literature at Hong Kong Baptist University, where she teaches fiction, poetics and modern drama. Her recent research focuses on the representation of Asia (in particular, Hong Kong and China) in Western literature and the intersection between Asian and Western literary works. She is founding co-editor of Cha: An Asian Literary Journal and an editor of the academic journal, Hong Kong Studies (Chinese University Press) and has edited or co-edited several volumes of poetry and fiction published in Hong Kong. Her first poetry collection is Hula Hooping (Chameleon Press, 2015) and she is the recipient of the 2015 Hong Kong Arts Development Council Young Artist Award in Literary Arts. She is currently a Vice President of PEN Hong Kong.

This post may contain affiliate links.