Tr. by Hester Velmans

That Minnie Panis wants to disappear is a result of her times and circumstances. This desire is embedded in the design of her makeup in the same way as the engineering error of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge — in 1940 the third longest suspension bridge in the world — was embedded in its design, eventually leading to its dramatic collapse three months after its completion.

The event was caught on film. You see the bridge span billowing more and more wildly, galvanized by its own momentum. Imagine that: asphalt and concrete, fluid as water. In the end of course the bridge crashes into the sea.

How Minnie Panis will disappear is most likely a matter of her training. She is a contemporary artist, hence she will disappear like a contemporary artist, which is different from how a bridge collapses, how the dinosaurs left the earth, different from the methods a biologist, a drummer, a physicist, a river, a dog, a truck driver, a lighting designer, a cherry blossom, a waste manager, a president, an elementary school teacher, a crystal, a puppeteer, a super intendant, a pilot, a cloud, a border guard, a doula, a coder, a banana, a building or a farmer would employ. While the how is a crucial part in recounting a disappearance, no disappearance can be understood or related to, if we don’t know what or who has gone missing, and in what context. Nobody will engage in pondering the question: “If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” if we don’t know, what a tree is, or what kind of forest we are in.

Minnie Panis is an artist who lives in Amsterdam. While something about her last name situates her sensual presence between penis and panic, her first name keeps reiterating, that she is “still childishly petite, which made her infinitely attractive to a certain type of male. That, combined with an asymmetrical face in which everything was just a touch off kilter. People, men, liked to read something wild and untamable in that face.”

Minnie was born prematurely. Her mother, a success in “the cancer biz,” raises funds to cure the world from abnormal cell growth. Minnie’s father is absent during her child-and adulthood. Artist boyfriends and lovers leave her. She owns an imitation Versace sofa that she sells, along with the rest of her belongings, for a conceptual, performative art piece titled: “Nothing personal.”

Minnie Panis was educated at an art school and supported by a market that specializes in feeding its consumers and connoisseurs images and ideas. She makes a living by performing, play-acting, documenting, artifacting, objectifying, and selling her conceptual ideas with the sort of urge, rigor, and strategic planning that triggers the press release or newspaper writers to use words such as “raw,” “naked,” and “intimate,” and to conclude their statements with sentences like: “The artist has vanished, erased against the white background of her stripped-bare home.”

Her repeated vanishings make her presence on earth even more prominent. She has shows in major museums all over the world. She has an agent, who refers to her as “a fucking genius,” she has sex with men. Her work gets crowned with the Prix de Rome and gets written about in magazines and newspapers. Without her prior knowledge, her sleeping, half-naked body is featured in the British Vogue on pages 82-92 in a fashion spread.

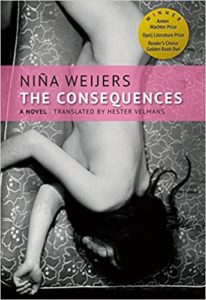

In her debut novel, The Consequences, Niña Weijers mainstreams Minnie Panis into a successful and fast progressing art career, and because the brutal shallowness of that cliché won’t last a novel’s lengths, Minnie starts insisting that she does not want to be an artist, which in the next iteration of herself, publicly headlined as an “Artist against her own will,” conveniently adds the authentic rebel edge that makes her foreseeably more appealing and powerful in the next art season.

“This is it baby! This is going to be your breakthrough. An artist who doesn’t want to be an artist, that’s fucking brilliant.” Her agent is excited about the “irony of a higher order”, which he demands should “not to be fucking confused with cynicism.”

How far can one go with that? How often can refusal be appropriated, marketed, sold and consumed by those who possibly cause it, before the only chance an earnest human has is stop making art?

The Consequences is in part about and part of the art world’s commodification of resistance. But it is also about the relationship of an artist to their art, and of the struggles of artists to represent what is absent.

After Minnie Panis has a retrospective at Hamburg’s Deichtorhallen titled: “Minnie Panis: Negative Selves,” she comes across the Cuban artist Ana Mendieta.

When she was beginning to break through, she fell to her death from her New York apartment window. Her body slammed with such force into the roof of the delicatessen thirty-four floors below that it left an imprint. To this day nobody knows for sure if it was an accident, suicide or murder, but that uncanny silhouette tied her life forever to her death, and her death to her art.

Minnie is fascinated by the mystery created around Mendieta’s death since 1985 when it happened, and quickly equates it with the mysteries surrounding artists going insane, becoming religious, dwelling forever in the limbo of their early promise or dying too young. Minnie sees mystery as an actual tool an artist can and should use to further their career. She calls it the “sorcerer label,” and it is that sort of cynical inclination to quickly label, explain, and make useful or sellable artistic practices that go beyond digestible bites, that occasionally renders Ninja Weijer’s writing shallow. For the one’s doing it, dying young or going insane is not a worthwhile act or a useful tool, employed to further their career posthumously, it’s probably more likely part of a radical practice. Through the act of dying the artist withdraws from the presence and leaves agency and control over the work floating around in an undefined universe, until the making of art history picks up the pieces and puts them together in any way it sees fit.

A death without dying makes as much or little sense as a life without living it and is as inconsequential as a story without words. Hannah Arendt says in The Human Condition:

Action without a name, a “who” attached to it is meaningless, whereas an artwork retains its relevance whether or not we know the master’s name.

But what if the artwork is not made of a tangible material shaped by the artist’s hands? What if the artwork is a performance and the performance the artist’s life? Isn’t it impossible to retain the relevance of an immaterial artwork without knowing who the artist was?

Can Minnie Panis’ art exist without Minnie Panis? Niña Weijers’ book keeps circling around this question, and the endeavor wouldn’t be well-balanced if the disappearance-obsessed Minnie weren’t equally obsessed with art world related presences and didn’t fly from Amsterdam to NYC to attended “The Artist is Present” by Marina Abramović, performed during her retrospective at MOMA in 2010, where Minnie sits — after hours of waiting in line — across from the celebrity and admiringly stares into her face.

That The Consequences is populated by many well known artists and illuminated by the description of their artworks is a beautiful treat for the part of the reader that loves learning about art history. However, those other parts of the reader, relentlessly habituated by story-driven characters like Rodion Romanovich Raskolnilov are irritated or disappointed by the fact that this coming of age story doesn’t develop with the intensity of Crime and Punishment.

Angela Davis said: “Radical simply means ‘grasping things at the root,’ and the scene when Minnie Panis most convincingly grasps something existential about life and its counterpart and beautifully relates it to us without having to rely on referencing other artists and their projects is the day she finds that female sheep in heavy labor lost on a meadow and brings it back to the farm, where the farmer tries to save the lives of twin lambs that have grown inside the sheep’s body by pulling them out of the womb with his hands. One lamb lives the other one dies.

Unfortunately, not everything can be explained through the simultaneous birth and death of twin lambs, and it might be very hard, but hopefully not impossible for a fictional writer to explain art with such effective and deeply moving silence, as Joseph Beuys did on November 26, 1965 during a phase in which he developed his “broadened definition of art.” For a performance at the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf he coated his head in honey and gold leaf and whispered into the ears of a dead hare, that he held in his arms, while slowly processing from artwork to artwork in the exhibit. “Wie man dem toten Hasen die Bilder erklärt” – “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare,” makes itself manifest as a paradox and possibly reflects, what Wittgenstein attempted to lay out in the Tractatus. There is a limit to the expression of thoughts in the form of language. In a letter to Russell, Wittgenstein asserts that the ‘main point’ of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus lies in the demarcation between ‘what can be expressed [gesagt] by propositions’ and ‘what cannot be expressed by propositions, but only shown [gezeigt]’, and one wonders if the “relatively famous author” in Niña Weijers book is a contemporary iteration of Wittgenstein, educated — like us — on the Internet and therefore accustomed to having complicated matters boiled down in a useful sentence or two.

“In writing, one principle trumps all other principles,” she had once heard a relatively famous author tell a group of young disciples. “Three words: show, don’t tell. If someone’s depressed, you don’t write ‘He’s depressed.’ You show that he is.”

A principle, Minnie thought, that must apply specifically to literature, since in real life people were depressed, sad, angry or hysterical because they said they were.

Is the difference between showing and telling the difference between writing and art-making? Do such distinctions make sense, or can a writer show that her main protagonist has disappeared within the mode of fictional writing? How would she do it? Leave the pages blank, make the story irreproducible, make the sentences incomprehensible, change the font size to 1.3 and make it incommensurable?

When Robert Smithson, who died at the age of thirty-five in a plane crash while surveying sites for his next earthwork, tried to define what he called the ‘surd situation’ (a region where logic is suspended) he established that a measurable size, will always exist in relation to a scale, which itself is not measurable because it’s always connected to our own subjectivity. He calls it the “scale of consciousness,” a metaphor for something, cosmic, vast and infinite.

Socrates supposedly never wrote down a word, he was suspicious of writing and material things in general and developed, taught and spread his ideas through arguments, discussions, debates and dialogues with his pupils. Eventually, his way of living, searching and teaching turned former pupils, tired out or threatened by Socrates’ never-ending embrace of uncertainty into his enemies, practical people who put him on trial for corrupting the minds of youth in Athens. During the trial there was a chance for him to escape, but loyal to his beliefs and his circumstances, he refused and drank the poison. Most of what we know about Socrates we know through the writings of his pupils, most importantly Plato, who was able to deliver the radical beliefs for which Socrates died, without having to die himself. But maybe that is just a story we’ve been told. Maybe Socrates hired Plato to write him into history, or Plato invented Socrates as a mouthpiece to speak his mind?

When the weather gets warmer, Minnie Panis steps on a frozen lake. She knows the ice is thin and the eyes watching her proceedings are distant, shielded behind the lens of a camera. Minnie steps forward and takes the risk to drown for the sake of art, pregnant with the child of a photographer, a man whom she can’t risk to love, because it might not be in Minnie’s design to love another human. In an act of revenge, she had manipulated the father of her unborn child to follow her with his photo camera to document her life (and death) for several weeks, hence when Minnie crashes through the ice, she doesn’t give up control. According to her planning, a photo is taken. With the employment of the photographer, Minnie obviously wanted to make sure her history would be created and preserved instantly the moment she would die. But would that photo have saved her a place in art history? Can history be made by living humans?

Minnie does not drown. The magic doctor who saves Minnie Panis when she crashes through the ice has already saved her life as a newborn and later as a seven year old child. After the rescue, when she sits in his villa in a white bathrobe he introduces Minnie to Lao Tze,

. . . a Chinese philosopher from the sixth century AD, who according to legend roamed around the country giving the people wise advice, which none of them particularly wanted to hear. Disappointed, he decided to withdraw from the civilized world. At China’s Western border he was stopped by a sentry, who convinced him to commit his ideas to paper. That book became the Tao Te Ching, or The Book of the Tao and Inner Strength.

On the Internet, Tao is translated as the way, path or route, and Taoism teaches a person to flow with life, and before Minnie Panis sets out to embark on her next artistic disappearance into region of Northwest China mapped out by google maps as desolate, she tries to find a tube of luxury Lao Tze Foot Cream in the Rituals Store at Schiphol Airport. The store manager is out of stock, so Minnie Panis buys a bottle of Wu Wei Bath Foam instead, before she gets on the plane and leaves us here, in real time and space, already eager to start reading the next book on our stack while still wondering if buying the Wu Wei Bath Foam is Minnie Panis’s very own and unique way to follow the flow of life as it was laid out for Minnie Panis.

The Tao Te Ching starts as follows in a translation by Stephen Mitchell:

The tao that can be told

Is not the eternal Tao.

The name that can be named

Is not the eternal Name.

The unnamable is the eternally real.

Naming is the origin

of all particular things.

Free from desire, you realize the mystery.

Caught in desire, you see only the manifestations.

Yet mystery and manifestations

arise from the same source.

This source is called darkness.

Darkness within darkness.

The gateway to all understanding.

Franziska Lamprecht is an artist who started writing as an extension of the long-term process based works, she produces together with her husband Hajoe Moderegger under the name eteam. Their projects have been featured at PS1 NY, MUMOK Vienna, Centre Pompidou Paris, Transmediale Berlin, Taiwan International Documentary Festival, New York Video Festival, International Film Festival Rotterdam, the 11th Biennale of Moving Images in Geneva, among many others.

This post may contain affiliate links.