The night before New Year’s Eve, I rode trains for over an hour to see Joseph Osmundson read from his memoir, Inside/Out. He read along with a few other queer writers; he read last, and with the least amount of finesse or confidence. He read his words quickly, stumbled over them, laughed to himself when he did. He read a passage about his ex, called “Kaliq” or “Tariq” in his memoir (as well as in his ex’s profiles on Grindr, on Adam4Adam, fake names that he would use “so that his boys couldn’t Google him after”), describing how Kaliq had taught him how to douche in a way that left him cleaner, and not wet in the way that he’d previously douched: “He liked a clean bottom every time. So I learned, and his brand worked the best for me too.”

He blushed and told the audience, “Sorry, my aunt is here. She’s going to hear this, and probably tell my mom,” and then continued. We all laughed. He seemed uncomfortable with speaking out loud, and he reminded me very much of how my old students would read their work out loud to each other when I used to teach college composition. I made them read their drafts out loud to each other, because you often only catch onto the rhythm of what you’ve made after you speak it. All of them hated it, and I kind of loved that.

I sat near one of his old friends from grad school, a sweet guy named Gerd (sorry Gerd, I don’t know how to spell your name), who offered me two beers from the six pack he brought along with him, which I thought was very generous, though Gerd shook it off. “How else am I going to get rid of six beers?” he said. We talked for a bit about Chicago, about the academic market (Gerd was a science PhD who was about to move to Manitoba for a tenure-track position. I’d only recently decided to leave my English PhD program, and while I congratulated him on his good luck of finding a position, I found that I wasn’t envious of him). The weather in Chicago, how it compared to New York State, where it turned out we were both from; how the weather would be in Manitoba; how anything would be in Manitoba. I asked Gerd if he’d ever heard Joe read before. He shook his head. “I read a few of his academic articles,” he said, “but none of his queer stuff.” I couldn’t tell if Gerd was queer—he was talking to me, someone who — though my external (and let’s be real, internal) gender remains inscrutable — definitely looks queer, and he was speaking to me kindly, and speaking only to me. Were we flirting? I don’t really know. I never know when someone is flirting with me, and I only rarely know when I’m flirting back with someone. I was drinking Gerd’s beer, so maybe I was.

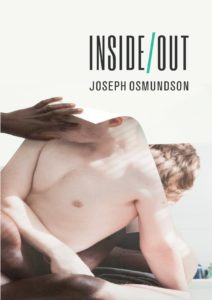

I’ll admit here that I definitely have a crush on Joe Osmundson. It’s one of those queer crushes where you’re unsure of its origin, but quite sure of its force. It might be because he looks like the kind of boyish person that I want to look like — and what, on my high self-esteem days — I believe I do look like: blondish stubble, light hair closely shorn on the sides, pink lips that are fuller than you’d expect, a body that seems both small and strong. I watched Joe as he came into the bookstore carrying a case of Heineken, as he stood behind a bookshelf, by himself in a short-sleeve turtleneck, with one hand wrapped around his torso and the other cradling his chin as he listened to the other readers, smiling slightly to himself (he looked, holding himself around the waist, almost exactly like the author photo on the back of Inside/Out, a satisfying bit of continuity). A few times, we made eye contact. I’m a Scorpio rising with a Virgo sun, so people’s first impression of me is often characterized (according to those I’ve asked) as piercing, silent, a little intense. And then we start talking, and sooner or later I’m rhapsodizing to them about how intensely color-coded my bullet journals are, and the fog of my mystique lifts abruptly. I can still be cute, though.

The reason I took trains for over an hour to see Joe read from Inside/Out is because I’d gotten up earlier that morning, and I baked chocolate chip cookies in my empty apartment while listening to Food 4 Thot, the podcast that Joe co-hosts along with queer writers Tommy Pico, Dennis Earl II, and Fran Tirado. Food 4 Thot is one of my favorite podcasts, and whenever I listen to it I find myself laughing out loud from pleasure itself, and from the pleasurable surprise that comes from feeling as if you’re listening in on a conversation that you feel part of, albeit silently. The 4 Thots are wicked and picky and sneaky and snarky, and I love every single one of them. But I love Joe the most.

I love his low, lispy voice and how even though he sounds nothing at all like the rest of the Thots, Joe will often preface what he’s saying with “This is Joe,” before launching into an explanation or observation — in answer to something else, in reference to some part of himself or his personality (he often characterizes himself as being “all in [his] feelings”) that he mentions not to defend himself, but rather to clarify, to agree with his co-hosts. He hums “yeah” or “so right” almost constantly when the other Thots are speaking. He talks about how much of himself he shares on his Twitter. He can always be counted on to preach the good word of poppers, and is a self-proclaimed “popper connoisseur.”

During this particular episode, the Thots were discussing the concept of being an adult, and what marks its arrival (or its abrupt and hopefully temporary exit) for each of us. Joe mentioned that he’d been working on a memoir that detailed the patterns of emotional abuse in one of his past relationships, and how it had been so difficult — both during the relationship, and after, as he was writing the memoir — to decide what the abuse had been like, where it could be defined as abuse, and who was responsible for it. He spoke about how his own struggle with understanding himself as an adult revolved around what you are supposed to do when you find yourself facing (and perhaps also producing) abuse, either in your personal relationships or in your outer community. Do you walk away, and sever all ties? Do you call it out to other members of your community? Do you try to negotiate with it, and how fruitful is that negotiation, in the long run? Is negotiating with abusive people effective? Is it effective to label people as “abusive,” or should you attempt more nuance and name their behavior as abusive, rather than them? Who’s abusive? Who isn’t abusive?

I listened to Joe asking these questions, talking about how these questions remained in Inside/Out, and I decided that I would definitely buy his book. On a whim, I reactivated my Twitter and searched for his handle and to my great surprise, I found that he was in Chicago! That he’d be giving a reading that night! That it was at 7pm, which is well within my limits for going out, since it guaranteed I’d be home and in bed by 10, with my bullet journals. I decided, it’s time to take yourself on a date. So I went.

For the past two and a half years, I’ve been in a relationship that has felt, at different moments and for so many different reasons, abusive. This person is my live-in partner, and one of the greatest loves of my life, of that I’m certain. But it’s been thirty months together (across oceans together and apart, in bedrooms of shared apartments together and apart, in homes we’ve built and made together and apart), and we continue to wrestle with each other, and we continue to wrestle with the question of how we hurt each other. How we can abuse each other, and how we can come back from abuse. How we can love each other and support each other without swallowing each other up in the abusive patterns of intimacy that have shaped us. We’re in couples counseling now, as well as in individual therapy, and I feel more secure about our love than I ever have before. We hold each other tenderly much more often now, and when we’re apart we tell each other so often each day, “i love you bb.” I love you. Joe and Kaliq were together for about two years as well.

So much of Joe’s desperation, confusion, and sweet aching resonated with me. He describes, both baldly and self-consciously, how inevitable and twisted their relationship became. How it never took much for Joe to run back to Kaliq, how you can never be sure of what you can trust: you? him? Love? There are pages of the memoir that are absent, but in a ghostly way. The word “REDACTED” stamps these pages, but there’s always a footnote attached, something that Joe couldn’t include in full in the memoir, because of what it would expose. Sometimes it’s a profile picture of Kaliq from a hookup app, sometimes it’s a text exchange between the two of them, or a text exchange between Joe and another guy who fucked Kaliq while they were together. No matter what, the redactions aren’t clean cuts. A lacuna is never a full absence, just like the number zero is always a symbol that marks nothingness.

I read the entire memoir on the train home, and found myself paying special attention to the sections that Joe had read out loud to us, to discern the difference between how they read on the page versus through his spoken voice. The memoir is divided into small numbered meditations, and they’re written sparsely. Never authoritative, but always sparse. Always powerful even in their humility. Kaliq is black, and Joe is white, and Joe wastes no time at all in mentioning this — it’s important to him that we understand what he knows: that someone’s personal context is derived from how the world divides us up, and the reality of Joe’s whiteness and Kaliq’s blackness means, for Joe, that he must be upfront about what he brings with him. He must acknowledge before he can describe. The cover of the book sets us up for this: we see Joe’s naked torso surrounded by a black person’s limbs, both of the them faceless, touching and separated at the same time. “The traumas that we brought into our love, the traumas that we enacted on each other, have everything to do with who he is and where he comes from, with who I am and where I come from,” he writes. “You can’t take it out of the story just as you can’t take it out of our skin, our bodies, our families, our memories, our love.”

While I was finishing up this review, my partner FaceTimed me as they drove to New Years dinner with my mother and my stepfather. I read the review out loud to them, and they laughed at the moments I’d hoped they would, and they told me they admired my honesty. We spoke about how our relationship affected my review, and how they had to be honest and tell me that it made them uncomfortable. “One of the things that’s always been difficult for me is the difference between what it’s felt like to be in this with you,” they said, “and what it’s been like to worry about how other people see it.” That’s always the issue, no matter what. Right, Joe?

G. Brown lives in Chicago and will definitely write about you in their bullet journal.

This post may contain affiliate links.