[University of Arizona Press; 2017]

[University of Arizona Press; 2017]

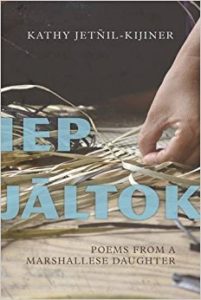

Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner opened the proceedings of the 2014 UN Climate Summit with story and poetry. Her clear, calm voice expressed her connection with her Marshallese ancestors and her concern for defending a future for her young child that includes a relationship with the shores of the Marshall Islands. Iep Jãltok publishes these poems shared in 2014 with a fuller context of the community and personal history that weights each world.

Iep Jâltok asks not only to be read again and again, but also that the reader hear its voice resound beyond the printed covers. Beautifully expressed and tightly constructed, Jetñil-Kijiner’s poems process how the violent environmental and social history of the Marshall Islands continues to be expressed in the daily lives of its people. Jetñil-Kijiner writes of the cancer that plagues inhabitants of the Marshall Islands who were subjected to catastrophic levels of nuclear testing by the U.S. during the Cold War, including the drop of a hydrogen bomb that obliterated an entire island. Iep Jãltok remembers the enforced hunger met with cans of spam and the racism of Hawai’ian middle schoolers during Jetñil-Kijiner’s years away from the Marshall Islands. The harm of the U.S.’s presence in this region is not just that of literal bombs falling, but also that of restricted and injured fisheries, structural and internalized racism, long-term health impacts, and language loss.

In “History Project,” Jetñil-Kijiner writes of the “political jargon” surrounding U.S. military action intermixed with brutal quotations: “90,000 people are out there. Who gives a damn?” Jetñil-Kijiner relates the U.S.’s mid-20th century dismissal of the Marshall Islands to the current disregard for the impacts of sea-level rise on the Pacific Island nations. The penultimate poem of the collection, “Two Degrees,” makes the continuation of environmental injustice explicit: “at 2 degrees my islands will already be under water,” she reminds climate change colleagues within the poem; “the Marshall Islands / must look / on a map / just crumbs you / dust off the table, wipe / your hands clean of.”

Of course, as Jetñil-Kijiner argues in a poem drawn from her childhood memories, history is not simply a project to post on a sign at a middle school fair. History is present in the lessons of daily life that Jetñil-Kijiner details with the painful precision of a middle schooler’s blunt cruelty and offhand racism. It is in the confusion of a Marshallese third grader wanting to be Laura Ingalls Wilder, despite the novel’s derogatory comments about “not wanting to turn brown like an Indian,” and in the pain of the young adult upon rereading Laura’s prairie scenes and hearing “the wheezing heave of hundreds of displaced feet / little girls with tree bark hands / sun browned / like me.”

Jetñil-Kijiner’s trim lines of poetry sharpen her points while preventing a feeling of poetic bombardment. Rather than sounding accusatory, Iep Jãltok encourages readers to join the poetic speaker in questioning the narratives of history and realizing the complexity alive in everyday diction and decisions. Its conversational tone is approachable in a way that contemporary poetry often misses without ever falling into the dull horror of sentences cut up like earthworms and stranded over many lines. I read poems in Iep Jãltok again and again, not because they were indecipherable the first six times, but because they resonated with such determination and beauty.

With deliberate accessibility, Jetñil-Kijiner’s poems narrate the layers of compounding harm that explain why the U.S. gives millions of dollars in foreign aid to the Marshall Islands: the reliance on food imports begun by a ban on fishing, the malignant health effects of major nuclear testing, and the ever-increasing threat of storm surges and sea-level rise due to climate change. No longer can we see the U.S. as giving “aid” to a developing nation; rather, we understand that these millions are meager recompense for the incalculable violence to the inhabitants, culture, and environment of the Marshall Islands. Iep Jãltok demands justice.

Yet, as if she watched her child play in the tide pools as she wrote, Jetñil-Kijiner never loses a sense of joy in storytelling and of hope for making choices that lead to better futures as she addresses both her child and those unknown. She writes with determination to resist submergence, to survive vibrantly. Iep Jãltok is the first book of poetry published by a Marshallese author. It is a spectacular beginning.

Emma Schneider is a graduate student at Tufts University. Her research focuses on North American and Environmental Literature.

This post may contain affiliate links.