Last month, when Emmanuel Macron defeated Marine Le Pen in the French election, a former college classmate of mine updated his Facebook status with a link to a Wall Street Journal article on the newly elected president with some additional commentary of his own. “Philosophers in high office to clean up the mess,” he optimistically added, in admiration of Macron, a former investment banker turned civil servant who began his untraditional political ascent to the top office as just another white man studying undergraduate philosophy. This was a beginning that my classmate and Macron both shared.

Last month, when Emmanuel Macron defeated Marine Le Pen in the French election, a former college classmate of mine updated his Facebook status with a link to a Wall Street Journal article on the newly elected president with some additional commentary of his own. “Philosophers in high office to clean up the mess,” he optimistically added, in admiration of Macron, a former investment banker turned civil servant who began his untraditional political ascent to the top office as just another white man studying undergraduate philosophy. This was a beginning that my classmate and Macron both shared.

A year into college, I, like these two, also declared a philosophy major. Part of me was motivated by an egotistical desire to insert myself into a tradition of smart people—one that I would later realize I do not really belong to. Most of me, however, was naïvely driven by the romantic allure of a field of study so archaic and uninvolved in real life—which, at the time, seemed much sexier than a lucrative career. The marketers of the American liberal arts experience sold me a dream at the tender age of 18. With my parents’ help and absolutely no idea of what I’d do once the degree was finally conferred on me, I bought it.

Other than the two times I registered for a LinkedIn account, I have yet to exhibit seriously any symptoms of buyer’s remorse. Looking back at all the philosophy majors I still keep in contact with, it seems like everything worked out, more or less, in the end. Part of the experience of being on a campus that oozes so much privilege is that whenever someone does decide to debate the merits of your degree by inserting yet another hackneyed joke about a prospective career at a fast food joint, you can laugh alongside your interlocutor in good fun—that the words deflect right off of you attests less to the thickness of your skin than to your sense of security.

An Atlantic piece on the distribution of college majors based on how much students’ parents earn, “Rich Kids Study English,” cites several studies that confirm what many of us already suspect. Children of privilege are afforded the opportunity to gravitate towards the useless degrees like philosophy or English. Anyone who’s gone to college could tell you the exact same thing. In fact, you don’t really need to go anywhere to realize that wealthy people can afford to burn their money without any consideration of a return on investment in a way that poorer people simply can’t.

Given these circumstances, money—and with it whiteness—can be found running underneath the philosophy programs of most colleges like groundwater. Despite the noted efforts of our department, it was undeniable that all the pasty faces there occupied a central position in this field of study in which I happened to find myself. Sitting in any discussion section, sometimes it really felt that if you weren’t white and male—that if you were even just white or just male—you were there as a courtesy.

When Joanna Ong accused her former professor and employer, the philosopher John Searle, of sexual harassment and assault, a friend and I exchanged some thoughts on the field of our former studies—we had both read Searle for a class we took together. “Man philosophy sucks,” I wrote over iMessage. “Lol,” he replied. As tragedies like these manifest themselves in other fields, the most appropriate reaction is often a boycott. When evidence of Bill O’Reilly’s sexual harassment came to light, advertisers pulled out, and he was canned. When accusations against Searle surfaced, however, some of the most vocal voices told us to do nothing at all. Though Jenny Saul, a philosopher at the University of Sheffield, insisted, “If you can avoid teaching/discussing Searle, that may be the best strategy,” instead of rallying behind her cause, fellow philosopher Brian Leiter disparaged her suggestion. On his eponymous blog, Leiter Reports—very popular reading for academics in the discipline—he wrote, “Is there some merit in [Saul’s instructions] I am missing? Or are they as outrageous as they seem from the standpoint of responsible teaching and research?”

Defense statements like Leiter’s serve to preserve the sanctity of philosophical champions. This rejection of Saul’s suggestion, I think, is motivated partly by an impulsive refusal to see one’s heroes, and perhaps oneself, as outside the scope of admiration. Advancements in philosophy, as our curricula indicate, depend precisely on the wisdom of men like Searle—and under no circumstances can we afford to set the clock back on progress. If Leiter is unable to separate Searle’s work from his conduct, it is perhaps because he too—as another powerful white man on the same path—operates under the same illusion of impunity. Regardless of all their questionable behavior, these men tell themselves, nobody can detract from their contributions to the academy. This delusional conceptualization of the self as being occupied with an inviolable higher pursuit is one that is all too common in the philosophy classroom.

A quasi-religious admiration of white scholars in the canon imbues in some students a shameless hubris and upholds an academic ecosystem acutely inhospitable to people of color. It is farcical yet true that a superficial resemblance to Wittgenstein alone was sometimes enough to demand exorbitantly charitable readers. During my years in college, not a single person of color dared to make a straight-faced illustration of Cartesian skepticism through unambiguous psychoactive drug references—how could you expect your professor to take you seriously?—while one white man who exclusively drank Mountain Dew did exactly that on more than one occasion.

What’s even sadder is the reality that this contemptuous climate, which seemingly elevates white scholarship above all else, persists far above undergraduate philosophy and is not something one merely grows out of. When The Journal of Political Philosophy published a series of articles concerning the Black Lives Matter movement last month, not a single black scholar was featured. On every level, white voices are granted an unparalleled credibility that is oftentimes disproportionate to what they merit.

Perhaps the reason we find ourselves giving more credit to white men on a college campus is as clear as what Baldwin writes in his essay “Stranger in the Village.” As Baldwin writes of the most pedestrian white men, “These people cannot be, from the point of view of power, strangers anywhere in the world; they have made the modern world, in effect, even if they do not know it.” Perhaps even the most illiterate and talentless white man living in a village in Bumfuck Nowhere, Switzerland belonged in the tradition of Shakespeare, Rembrandt, and Beethoven more than Baldwin ever could.

Perhaps the reason we find ourselves giving more credit to white men on a college campus is as clear as what Baldwin writes in his essay “Stranger in the Village.” As Baldwin writes of the most pedestrian white men, “These people cannot be, from the point of view of power, strangers anywhere in the world; they have made the modern world, in effect, even if they do not know it.” Perhaps even the most illiterate and talentless white man living in a village in Bumfuck Nowhere, Switzerland belonged in the tradition of Shakespeare, Rembrandt, and Beethoven more than Baldwin ever could.

Every so often, even the most unprepared freshman from the whitest town in backwoods America imagines himself to be following in the footsteps of Saul Kripke and David Lewis on the first day of class, without any familiarity with the subject. In these situations, the rest of us in the classroom merely assume, in his eyes, the role of Platonic interlocutors, sitting there like hurdles between the mighty philosopher and his coveted participation grades. Even worse, numerous horror stories still circulate of prospective students on college tours, sitting in on classes, injecting themselves in collegiate classroom discussions about Kant and Foucault without having first made a decision on where to attend college—or reading the material at all.

The citizens of Plato’s Republic accept that the voluntary subjugation of themselves to the rule of the philosopher is for the best. And any narcissistic reading of Plato—whether or not induced by Mountain Dew—is sure to convince the privileged adolescent reader who already fancies himself as belonging to the cherished lineage of Socrates-Plato-Aristotle that he too can reach out and touch the Forms.

Sometimes, as I attended to the most long-winded arguments by precocious know-it-alls talking down at me, I wondered why I was still listening and engaging. I spent six months of my senior year watching a student infuriate the entire room by taking the extreme view that Huckleberry Finn unequivocally should not have enabled Jim to escape from slavery, as Huck knew he was acting against his moral conscience—a position that he would later backtrack on in favor of something more commonsensical. Did the confidence of my interlocutor overwhelm me to the extent that I managed to convince myself that hearing him out was, as in the case of Plato’s citizens, somehow in my best interest? If so, what a terrible waste of six months’ time that was.

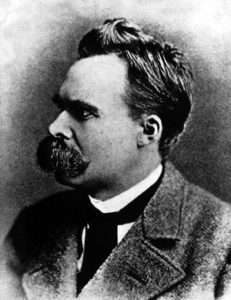

With this in mind, it might be easier to understand why the philosophy classroom looks the way it does—so hostile to minorities—and why my classmate, an intelligent now-graduate student in philosophy who is typically more capable of producing a nuanced view, had sung such unabashed high praises for Macron, a relatively inexperienced politician with no longstanding track record. Probably out of sheer frustration, a professor once told his entire compulsory freshman humanities class that if it were up to him, he would expunge works by the likes of Nietzsche from the curriculum altogether so that he would have fewer pimply-faced teenage boys roleplaying philosopher kings—exercising their will to power without restraint and grossly miscalculating their domains to extend throughout the discussion table and, occasionally, beyond it.

With this in mind, it might be easier to understand why the philosophy classroom looks the way it does—so hostile to minorities—and why my classmate, an intelligent now-graduate student in philosophy who is typically more capable of producing a nuanced view, had sung such unabashed high praises for Macron, a relatively inexperienced politician with no longstanding track record. Probably out of sheer frustration, a professor once told his entire compulsory freshman humanities class that if it were up to him, he would expunge works by the likes of Nietzsche from the curriculum altogether so that he would have fewer pimply-faced teenage boys roleplaying philosopher kings—exercising their will to power without restraint and grossly miscalculating their domains to extend throughout the discussion table and, occasionally, beyond it.

Indeed, planting such fantastical narratives into the minds of self-important teenagers can only germinate equally misguided perspectives through which they see the world. In this vein, their lives and the lives of all others operate within this greater vision, with their own successes perceived as inevitable and their unexpected failures perceived as injustices. Macron’s political rise appears anything but pre-determined, but in the eyes of my classmate, real life perhaps unfolds with the same teleological perfection that the ancient Greeks imagined. The philosopher kings, in the end, ascend to the throne. The rest of us are here to watch.

Edwin Jiang is a freelance writer living in London, UK.

This post may contain affiliate links.