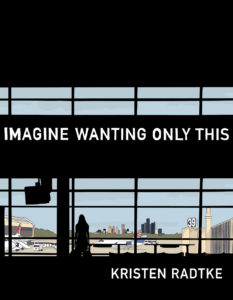

Yesterday, I went to the coffee shop to finish writing a review of Kristen Radtke’s debut book, a smart and funny graphic memoir called Imagine Wanting Only This. I ordered an “equal parts Americano,” told the barista about the missionaries who I’d talked to on my way over. How earnest and naive the young men seemed; how incomprehensible their lives are to me and mine to them.

I sat down and reread the draft. It was fine, maybe even finished. In it, I made a sequence of belabored arguments about how the book depicts ruins and abandoned places, it’s relationship to the video essay (a form Radtke has worked in extensively), and notions of immortality through literature. The observations were not unintelligent but nevertheless were uninteresting; not even I cared about what I was saying.

I sat in the cold coffee shop, staring into middle distance as I waited for my girlfriend to get off work and pick me up. It was a shame, I thought. I’d been so excited about the book, but none of that excitement had made it into the review. What was it that was missing? What had excited me? Part of what had excited me was something that doesn’t usually make for compelling criticism, that is, I had found Imagine Wanting Only This to be relatable. I, like Radtke, am fascinated by the problem of comprehending the past and by art and literature that hold space for the unknown or unknowable. But how embarrassing it is to be one well-educated, white girl relating to another. I’d finished my coffee by the time I realized that the idea of relatability had a place in my review, that Radtke’s whole project was one of negotiating out the extent to which it is possible to feel one’s way to a past, a future, an other, that can’t really be known.

***

Sitting at my desk that evening, I looked up “relate” in the OED. There, I found that my fuzzy understanding of “relatable” was actually only drawing on the most recent meaning of relate — To understand or have empathy for; to identify and feel a connection with. The first cited instance of this usage is a 1947 Social Work Year Bk. It’s a therapeutic notion, born out of a particularly modern means of pursuing self identification.

Some older meanings of relate: To bring back, to restore; To recount, narrate, give an account of (actions, events, facts, etc); To be retrospectively valid; To connect, to link; and, since 1847, To have a connection with or stand in relation to or have an origin in a previous event.

In Imagine Wanting Only This, Radtke narrates a version of her life that places special emphasis onto her research into and attempts to imaginatively restore the unknowable nuance of the past. Accounting for the past in this way links the past to the present. Radtke’s memoir relates and relates to the past.

In a journalistic attempt at transparency, I’d like to tell you, dear reader, that Radtke’s depiction of herself — in tight jeans and a sweater and sitting rather glumly in the dark on the steps up to her friend’s house, talking on the phone to the friend who is visible in the upper right window of the house above — felt familiar. I’d like to tell you that I ached with recognition reading the older Radtke’s narration, “I didn’t want to sit still, but I didn’t want to lose anything either. I wanted to gather more without giving anything up.”

I understand that you can’t have it both ways and that even if staying still it will be necessary to give things up. I understand, as Radtke writes later, that “Nothing is permanent:” that there is death and disease, war and regime change, earthquakes and fires. I believe what’s been said, that someday soon Manhattan will flood.

There are, however, moments that I glossed over in the earlier version of this review, where Radtke’s thinking is inconsistent with mine, and, I think, with hers. In the final, cinematic sequence of Imagine Wanting Only This, and over images of apartment living, an abandoned and crumbling apartment building, crashing waves and the milky way, the silhouettes of mountains in the fog, Radtke writes:

It doesn’t matter that your feet are touching the ground they’re touching now. The floors will rot the carpet will be torn out, the cement will crack and shift and be pulled from the earth, the dirt will be tilled and changed and rained away, and someday there will be nothing left that you have touched. Who knows which pieces will matter? Who knows what will be significant when we have all moved onto what is waiting or not waiting. You will have touched nothing on earth

In the first sentence, Radtke says it won’t matter whether you’ve touched the ground for it will all pass, and in the last she says that you will have not touched anything. Someday, sooner or later, the earth won’t belong to us any longer. But just because something is far away or seems mostly irrelevant doesn’t mean that it isn’t relatable — an event of the far-away and imagined future can be recounted in the same breath as the present, an event of its past. Just because something passes, because one day it will no longer have a framework to matter within, doesn’t mean it didn’t happen, didn’t matter.

There’s a rather delusional notion, which I availed myself of as a seeking undergraduate, that a piece of literature can confer a sort of immortality to both its writer and subject; and while books are nearly as vulnerable as human life in the face of disaster, the book as object and as idea can narrate the past and the present into an uncertain future. And, anyway, it seems that the fact of Imagine Wanting Only This, the effort required to bring it into existence, seems to hint at a far-off hope that maybe, someday, some part of this, or something derived from this, will be a piece that matters, that is, significant.

Cypress Marrs has written for Bomb, Lapham’s Quarterly, and The Los Angeles Review of Books.

This post may contain affiliate links.