[ON Contemporary Practice; 2016]

[ON Contemporary Practice; 2016]

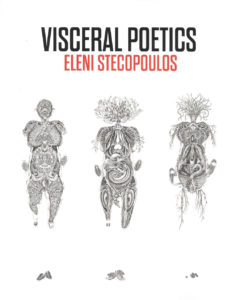

Entering Eleni Stecopoulos’ Visceral Poetics feels like descending into rushing/ebbing oceans. As a reader you must dive towards without reason, surrender so that you are better able to float along the effervescent rhythms, thick intertextualities, depthless questionings.

While closely studying the bent, maddening language of Antonin Artaud as a graduate student, Stecopoulos began experiencing unexplainable chronic pain. In response to unsatisfactory encounters with U.S. doctors (and Western approaches to health in general), Stecopoulos traveled through different healing modalities and their attendant “cultural cosmologies,” writing about each experience as a method of processing these counter ways of reading the body. Soon this bodily writing merged into her interpretations of Artaud, a commingling met with warnings and uneasiness from her academic peers. The crossing of disciplines (and boundaries) is dangerous territory. But why must body stay separate from scholarship? The same question can be extended to include familiar vexing binaries: self and other, health and sickness, interpreter and interpreted, sense and nonsense, mind and body. In the medical world the term psychosomatic refers to the physical manifestation of psychological distress, a pathology based on the interaction of body (soma) and mind (psyche). As Stecopoulos points out in an installment of Thom Donovan’s somatics questionnaire, the West’s over-determining trust in Cartesian division has left us with language that diagnoses the merging of mind and body as diseased, hysterical, threatening. To follow that logic is to be lead here, an impasse: to be healthy and whole is to be separate. To be complete is to be ruled exclusively by the mind: “[h]ealth in American society is tantamount to not having a body.” This separation seems to evoke discernment, rationality, and coherency, but Visceral Poetics points towards all the leaking holes. A language (and by extension consciousness) of unrealized, swallowed up meanings: “ . . . even evoking ‘the body’ is evidence of the rift — even considering the body as something discrete, an object of study that can be set apart from other bodies or sentient beings or ancestors or cosmos.” What fantasy does a separation enact?

Stecopoulos considers the resonating legacies of such a split, tracing equivalences between seemingly disparate and wide-ranging fields. Visceral Poetics emerges from and sews together many tender points: medicine, somatics, philology, colonialism/imperialism, poesis, translation, ontology, holistic healing, occultism, autoethnography. The work of Artaud and Paul Metcalf become sites of ecstatic unreadings, encounters with texts that thwart the reader’s efforts to easily consume, digest, know. The text’s investigations into the languages and methods of Artaud and Metcalf seek to expand and complicate discourses surrounding their experiments and beyond. Artaud the mad poet, scribbling gibberish during his many hospitalizations. Paul Metcalf exorcising the weight of Herman Melville, his great-grandfather, through his novel-in-fragments Genoa. In both scenarios, their writings are evidence of a deeper pathology: Artaud’s neurological disorder, Metcalf’s neuroticism. Writing as disease. But what if language emerges as a homeopathic modality? The text turns to Jean-Jacques Lecercle:

In his work on délire, or “the reflexive delirium” of Artaud and other writers . . . who demonstrate a link between grammar and madness, [Lecercle] argues that the poetics of these “logophiliacs” cannot be separated from a subversive commentary on all systems and structures…. délire is by no means irrational, but rather anti-rational ─ intervening into structures of grammar and pathology, overwriting them with other myths . . .

In French délire denotes delirium, nonsense, disordered language. Since lire means to read, embedded within délire is another connotation, to un-read. Reading as delirium, delirium as a kind of (un)reading. Through their unconventional grammars and forms, Artaud and Metcalf telegraph out-of-bound idiolects full of bodily fluids, empathetic gestures, Western malaise turned mythology, deformities and “extravagant reading,” an unfixing of language and structures chokingly-caught in rationalism’s segregated thrall. Logophilia, or the love of words, contains the Greek suffix –philia, which in one sense means fondness or love and in another sense (pathological) refers to an abnormal infatuation or tendency. Within the love of words rumbles a perversion, a seeking that drifts away from language as mechanical tool towards its emanating, vital presence and potentials. A submerged language that must stay silent and untranslatable like the body in pain. Rather than viewing abnormality as communicating a deficiency or faultiness or alienated singularity, Stecopoulos argues for the recuperation of the pathological, the sick, the mad:

Artaud and the Chronic Fatigue sufferer make anagrams out of everything because confusion helps the confused by assigning an order, however random. The anagram calls attention to both the arbitrary nature of arrangement and to the significance any (arbitrary) movement will reveal was there all along. The anagram exposes the artifice of official order; it denaturalizes the authority of the whole.

Whose whole is natural? We swim through mentions of hermetics, Édouard Glissant, Artaud’s “translation therapy,” Loudun possessions, clubfoot, Greek etymologies, 9/11, meridians, and more. Fragments cross into symptoms, while myths construct a mirage of wholeness. Through rearrangement subtler knowledges appear; what takes hold is not the clarity of what is uttered/written, but the correspondences between fragments and blocks, embodiments and stutters, their mysterious relatings. Xylophonie/Xylophénie are terms Artaud used to describe his language. Words buried in words, meanings that will not see themselves as reducible or parts of. His idiolect resembles an instrument, hammers striking bars. Xylophénie is a neologism bringing together wood, phenomenon, xylophone, and schizophrenia: “By splintering it into disorder, limitless combination of notes on a restricted block of wood, Artaud terrorizes language into the xylophone it pretends not to be.” In Genoa Metcalf articulates a body of contact, diving and monstrosity. Stecopoulos compares the movements of his text to reflexology; Genoa massages the connective tissues between American letters, conquest and decay, through a narrative of two brothers and woven-in excerpts from Melville’s novels and letters, Columbus’ writings, travelogues, and medical textbooks. Stecopoulos meditates upon the anxious feedback of Metcalf’s charged islands, as he documents/sculpts an “oceanic” relation in process, where reading and writing uncover moments of bodily plunge and ecological return.

Stecopoulos links her healing journeys to these textual odysseys undertaken by Artaud and Metcalf, voyages threaded, buoyed by a desire for origins. Crashing and enfolding Greek, Turkish, Latin/Romance puns, Tarahumara, Sanskrit, an analphabète, Artaud gesticulates his anti-alphabet, ironically in search of a pure linguistic-bodily source. Just as Stecopoulos went off in search for the genesis of her illness, as Metcalf attempts to locate “the Western body” through its texts, wounds, and drownings. A crisis in health (or wholeness) leads to estrangement, a journey outside of the self and into the other. But if the mind/body split is a precarious illusion. What to make of the divide between self and other, particularly when involving healing, medicine, and language?

“It is as much as an epistemological legacy of colonialism to divide the world into oppressive heads and suffering bodies.” Colonialism creates an unbalanced exchange, where the colonizer displaces their body onto the other, most recognizably via labor. Visceral Poetics reminds how this division has burrowed its way into the sciences, thought, literature, and beyond. Philology came out of contact and conquest, a need to classify the languages of the world and invent Europe-centered myths of origin. “Ethnography inherits a thinking through the raw matter of the other,” wherein a researcher (mind) makes sense of a culture (body). Criticism carves down an opaque text into an anesthetized object. Similar exchanges lurk beneath alternative healing narratives. Artaud travels to Mexico, living among and studying the Tarahumara people, driven by an interest in gestural language and the desire to heal himself of addiction and pain. During her healing quest Stecopoulos encounters Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurveda and shamanism. These moments of contact provide a complicated knot of relations. In placing the fragments side by side, the text cannot ignore how a journey to heal the (Western) body inevitably leads to a reencounter with our colonial origins. A relation that has been occluded by overwriting myths of division and universality. How to heal, or reanimate the body, without recreating imperialist logic?

Visceral Poetics links those deemed barbarian to a body in pain, to a designation of untranslatability. Just as an other is reduced to stuttering language and primitive gestures, a body in pain, or exhibiting mysterious illness, is known by its “supposed inarticulateness,” a regression from the normalized. However, for Stecopoulos and others, this very inarticulateness can unleash kinetic modalities silenced by the totalizing mind/body split. To recover the body entails a remembrance of fragments and wholes, amnesia and viscera, a willingness to estrange and recombine. The text argues for a literature of “process and the chaos of failure,” or a heretical literature ― one that does not pretend writing or reading is not bodily, alchemical, a process of and for reintegration. Poetics of Healing was a series of events curated by Stecopoulos from 2008-2011. These public programs came out of this text, an activation of her empathetic criticism and journeys.

How to uncover your body’s vital intelligence? Stecopoulos argues that the possibilities are limitless and cross a range of disciplines and notions of being. She sees poetics as helping hands, poetry as affinitive touch. Visceral Poetics makes the eccentric intimate, plunging us into a text where fragments hold one another rather than explicate. Poetry shouldn’t be after a root that will explain all. Rather, poetry should revel in its opacity, a term borrowed from Glissant, which he used to describe the “irreducibility” of a language and/or people: “that which cannot be understood or rendered transparent by an attempt to translate.” Divides must be addressed, but for Stecopoulos our Western methods of allopathic intervention too closely resemble a “search and destroy” logic. In her travels through health, “words, vocables, writing, and philological aura” exist as medical technology, a healing unconcerned with rational meaning or uses. “No book can hold the whole body,” and why should that be its only goal?

Allison Noelle Conner lives in Los Angeles, where she works as an assistant fiction editor for The Offing.

This post may contain affiliate links.