Tr. by Natasha Lehrer and Cecile Menon

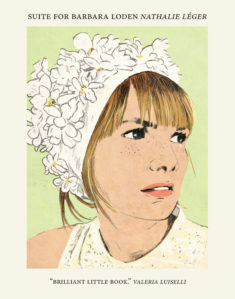

Nathalie Léger claims to have begun Suite for Barbara Loden as a brief entry on the American actress and director Barbara Loden for a film encyclopedia. Loden was married to the filmmaker Elia Kazan, had a brief acting career, and directed one movie, Wanda, in which she played the title role. Wanda was based on the true story of a woman drawn into a bank robbery. Her accomplice tells her that he will kill her and then himself if the heist goes wrong. Instead, he’s shot to death by the cops, and she is left to face justice alone. Wanda is a figure of overwhelming passivity, framed in the first shot of the movie as a tiny figure that dust “absorbs and dissolves” as she picks her way past a blurry pile of slag. She is an unresisting, pathetic creature, so panicked by her robber boyfriend’s instructions that she can hardly memorize them. She has them written out in a list: “14. Put the money in a bag. 15. Go to the car and leave.” Léger, assigned to write about Loden for the film encyclopedia, becomes obsessed with Wanda, and instead of finishing her entry, embarks on a study of coal mining and hair curlers, Polish immigration and the history of the self-portrait, spiraling out from her subject rather than honing in.

Suite for Barbara Loden becomes an urgent investigation of the vanished actress, her character, and of the woman Wanda was based on. Léger travels to the United States to view the landscape where the movie was shot, disregarding her rental car’s GPS to wander through coal country. She calls the governor of the prison in Ohio where the real Wanda, Alma Malone, had been incarcerated in 1960. She also relays Barbara Loden’s conversation with an earlier governor of the prison, who had refused her access to Malone. Loden had explained to him her interest in the inmate, but we see that her status as actress and director means absolutely nothing to this man of authority. Here is the real voice of power, in flat refusal: “No, said the governor, I don’t think it would be interesting, I don’t think that you should be interested in this story, I’m the person who gives permission for everything here, and that I will not allow.”

Léger’s book-length essay or film study or novel is a reaction to this judgment and withholding of permission. She dares to be interested. Women like Wanda seem pitiably weak, and yet their weakness is its own kind of strength. Loden played Wanda herself rather than assign the role to another actress because she strongly identified with her. Loden had been a runaway, a pin-up girl, a dancer in a nightclub, before getting cast in films. She told an interviewer, “I lived like a zombie for a long time, until I was nearly thirty.” She met Kazan when he was a successful director in his fifties, and she a mid-twenties blonde beauty in an acting class. He wrote a novel, The Arrangement, about their relationship, then let Faye Dunaway play the lead in the film version. Léger imagines this as a bitter betrayal. She questions her obsession with Loden, saying she herself has never been homeless, has never given her existence over to a man. Yet she remembers one bleak scene from when she was fifteen, when it was “impossible in moments like that to think that defending my body could be worth the effort.”

Here’s an admission of an intense degradation, that is however so run-of-the-mill for women that it’s not even worth describing in detail. The subdued anguish of the book resonates out from this admission, which seems central to the way violence against women is constituted: we can come to see our own bodies as not worth defending. Léger depicts herself in this book as organized and hard-working, caring for her mother while also having the wherewithal to fly across the Atlantic to do research. This accomplished, driven writer nevertheless shares a core of emptiness with Loden, and with Wanda. When the film came out, Léger writes, feminists criticized Loden for focusing on such a passive, subjugated woman. Yet this story we should not be interested in won’t stop its peculiar pull. Léger stubbornly sticks to it, magnifying Loden’s tale and making it her own. The book becomes an autobiography, “a woman telling her own story through that of another woman.”

Suite for Barbara Loden comes across as a dream, grounded in the women Léger researches but flowing into aspects she brings to life through fiction. She quotes Loden in an interview about her role in the Arthur Miller play After the Fall. Then the scene takes up as the door closes on the interviewer, and Loden sits in her dressing room. “She could hear noises backstage, the dresser going back and forth carrying costumes between the dressing rooms, the squeal of hangers on clothes rails, the echo of footsteps in the wing muted by thick carpet . . . ” The point of view has shifted without transition, a hallucinatory transposition of the narrator for her subject. Léger paints the bleak landscape of Pennsylvania and an improbable interview with the elderly baseball great Mickey Mantle with the same hypnotized attention, as if moving through the vacuum a deep wound has made. The book absorbs in its absorption, its willful fixation on a subject she should have passed over altogether, or at the least done less with. “It was understood that it was easier to fail than to succeed,” Léger writes, “the implication being that the most effective way to succeed was to fail.” Though she has failed her editor’s request to “stick to the subject” of the encyclopedia entry, the book is a quiet victory, reclaiming Barbara Loden’s persistence and nerve even as she is denigrated and misunderstood.

Angela Woodward is the author of the novel Natural Wonders, winner of the 2015 Fiction Collective Two Doctorow Innovative Fiction Prize. Her other works include the collections The Human Mind and Origins and Other Stories and the novel End of the Fire Cult. She can be found online at: www.angelawoodward.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.