[Rescue Press; 2016]

[Rescue Press; 2016]

“Before I survived,” writes Zach Savich in his new memoir, “I wrote this.” Savich — poet, educator, young, and married — has cancer, and notably not for the first time. His book arrives in the unsteady moment of so-far survival as an archive of many moments that might have — and might still — prophesy a different ending. “There is a book you write,” he says on the last page, “when you think you will not be able to write anything else.” For Savich, that book is Diving Makes the Water Deep.

Susan Sontag writes, “Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick”: Savich’s first diagnosis came at thirty, a mere three months after his “father died at sixty from the same cancer.” We learn about Lynch syndrome, microsatellite instability, an inherited condition that causes cancer; we learn that this kind of cancer also took the life of Savich’s paternal grandfather and likely punched Savich’s ticket into the night-side of life.

Savich’s memoir is written in a state of self-reflexivity: the book is always already contending with the idea that Savich may not be around to finish it. “I think of the birds that sing not to be heard but to continue. Or those that nest in shopping carts. It isn’t art, exactly,” Savich writes. The self-elegy, he admits, “is a critical term, I just learned, don’t have time to learn about it.” And yet it’s exactly what he’s written. The self-elegy, which poet Matt Rasmussen calls “the most honest, direct, and pure strain of elegy,” requires the writer to occupy multiple stations at once — that of mourner and of mourned. Savich writes, “Say [cancer] and conditions that should be obvious, ever-present, to anyone who has loved or read — that we are fragile, impermanent, not in control, afflicted with unreasonable joy in the midst — become a story you can tell, external. But I still prefer experiences that are not easily worded. The experience of cancer is not ‘cancer.’ The unapparent is still larger.”

To call the work a cancer memoir, though, would be limiting. As much — if not moreso — about friendship, correspondence, and an abiding devotion to poetry, Savich vacillates between reminding the reader of the very real peril he’s experiencing, and trying to shirk the weight such a reality might put upon both his writing and the time he has left. Savich “cannot stomach the popular accounts of affliction” and, as he does elsewhere in the book, turns to catalogue his appraisal of particular kinds of literature. Some of the problems with memoirs of the sick, according to Savich, include: “Treating narrative as a structure, rather than a struggle. Showing affliction then insight, as though insight (presented as inseparable from tired narrative patterns) can save us. Fucking redemption. Isn’t every work of art about suffering? So illness memoirs are redundant.” Still, Savich’s book is as far from an illness memoir as it is from self-elegy — is closest to what Keats once referred to as “the posthumous existence,” which marked the time after the death of his brother, but before Keats himself would bid the world goodbye with his “awkward bow.” Savich lives his own altered version when, on the way to a job interview, he learns his father has died; Savich continues on to the job interview, then quotes Robert Creeley, “In those stories the hero/ is beyond himself into the next/ thing.” The difference is that Savich’s next thing might be death, but isn’t.

In the place of redemption and in what is the central heartbeat of the book, Savich offers the following passage:

“It’s not the dying but the disentangling,” my father kept saying. Meaning: we should wish for further entangling, entangle, entangle and surge. The melody is already enchanting and already not endless enough already why not sing several.

Entangling: a way to practice beginning again. To entangle one’s self further: a way to keep singing. To surge: to grasp at the ineffable. Perhaps, for a poet, any kind of entangling is redundant. “Illness is an inherently lyrical state,” says Savich, but then he also quotes Rilke, “Here is the time for the sayable.”

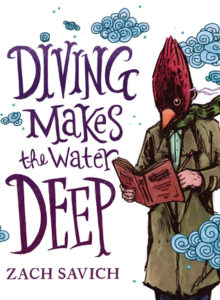

The title page of each chapter features a beautiful graphic novel-type illustration of a man, made birdlike, by artist Christian Patchell. The bird man wears a mask and a coat and sometimes he is making things with his hands. Each chapter is organized into numbered prose blocks and many entries stand on their own like small, neatly wrapped gifts (in one of the illustrations, the bird man holds out such a gift). The entries are meticulous and insightful, entangled in the world of poetry. In one such entry, upon being asked to justify the existence of poetry, Savich asserts, “Justify why you have an eye. How come nursery rhymes, how come tulips and clouds, fear and bread, insight without immediate application.”

In another, speaking of memory, he offers an enumeration of lines he can recall:

That for days I have woken with a phrase from Agha Shahid Ali lighting the slowly lighting room: “Hurt into memory.” Compare to Dickinson: “Remorse—Is memory—Awake.” Or Richard Wilbur, on waking: “The soul shrinks // From all that it is about to remember.” Langston Hughes: “I don’t dare start thinking in the morning.” Alice Notley: “The goal of awakening is black coffee.”

While Savich seems, at times, to be perusing the shelf space in his own mind, at others he is reaching out to friends for answers. Many of the passages are taken from direct correspondences with friends, whom he unabashedly adores — “Loves,” he begins one e-mail—and many of his friends are undoubtedly writers. Like Savich, they share unequivocally in the joys of entangling as daily praxis. These friends and their conversations become the buoys that keep him afloat.

On the other side of such affection — and, it seems, not always with the ease of lighthearted banter — are entries that go after contemporary poets. Savich doesn’t name names, but seems to bemoan the idea of poet as persona. With tongue in cheek (or so the reader is told), he takes on poets who gaze into search engines and those that write poems on boredom or dissatisfaction, or poets who spend time name-dropping more famous poets at parties.

“I’m trying to read poems instead of reading what people are saying about poetry online,” Savich says in one such entry, “the commentary and corrections, media cycles of instant response and what do we agree we all hate today (I am thinking about a particular spat, will not record it). I find there is usually more in the poems.” In the end, this seems both fair and relevant: “I still find pleasure raging at bad writing.”

While some entries last the length of an average tweet, others are longer and markedly more lyrical, bleeding from one numbered section into the next. Some are dreamlike; some are expository; and many denote the passing of time and signal an arrival in the future, even if arrival is complicated by the dramatic irony of death. What’s true of all the entries, however, is that they maintain an incredible presence and convey to the reader a sense of the book being written in real-time. There are fragments and moments of repetition, both adding to the tension of time and brevity. Toward the end Diving becomes more and more urgent as Savich becomes “full time sick.”

Poet David Rigsbee argues that, “To elegize is to sing about the end of things . . . even as it is about memory and legacy. At the same time, as its song borders upon silence, to elegize also suggests something about how poets, as language users, devise beginnings — often ironic — in the face of discontinuity.” In this way, the edges of memoir and poetry are blurred, relying on memory and imagination concurrently. While memoirists often explore that which is already behind them, much of Savich’s illness lays out before him with no guarantees. It is in this moment that Savich tries to live (and record) all his past lives at once: he is reading a book near a river or at a window or where it is snowing or raining or threatening something from the sky; he is falling in love; he is hearing a poem for the first time; he is unwittingly breaking someone’s heart; he is sick and not sick and sick again.

Zach Savich’s prose wears the mark of the poet’s charge: to direct attention, to engender curiosity, to chronicle insight, and — especially in Savich’s case — to suspend time. Diving Makes the Water Deep does so despite the guarantee that none of it may matter in the end. At once an invitation to the intersections of mourning and illness (both embedded with incomprehensible types of loss) and a living installation on possibility, Savich’s memoir calls for further entanglement, for humor, for “unreasonable joy in the midst,” and for momentous ways of being in conversation with the world. Savich’s hand is out, gesturing to the reader in the incantation of Rilke, or Frost, “You come, too.”

Chelsea Reimann is a fiction writer and book artist.

This post may contain affiliate links.