[Letter Machine Editions; 2015]

[Letter Machine Editions; 2015]

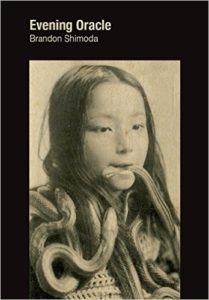

The cover of Brandon Shimoda’s Evening Oracle — a shimmery, porously-bordered book which recently won the Poetry Society of America’s William Carlos Williams Award — is a young Japanese girl with three snakes draping her shoulders. She is holding one in her mouth too, gently, her teeth cupping its neck not crushing its head. Her eyes are soft, the right a little lazy or else the camera makes it look that way. The girl is either dressed or bound in a cloth somewhere between rope and lace, and her hair might be greasy. She is an entertainer, the citation tells us, “The World’s Greatest Bear Girl,” and it’s important to note that the picture is not scary at all, unless we ask ourselves where the bear is. The snakes seem manageable. Her eyebrows are relaxed.

Why is this girl here? Why is she protecting the book without meeting the reader’s eyes? Answering this is in many ways completely beside the point. The girl is here. We should look and listen. Indeed one of the most beautiful things about Evening Oracle — which is, I think, a beautiful book, elegantly wandering but not lost — is that its goal is not comprehension so much as communication. A proof of bodies corporeal and not, in places and interacting with other bodies. Shimoda wrote the first drafts of most of these poems in beds in the homes of friends and strangers in Japan, July-August 2011 and July 2012. There are also a couple of drawings, a still from a film made by his sister Kelly, and prose-shaped excerpts from letters to and from friends (in this way, neatly, Evening Oracle echoes and maybe answers Williams’s book Paterson, which draws at length from correspondence too though unlike Shimoda, Williams did not print his replies). Thus Evening Oracle is an intimate book, written in the hazy-blue hours before sleep, and maybe occasionally cryptic as well, not because Shimoda is a myopic writer but because he is accurate. Ghosts and broccoli soup and sadness and six lemons are all sometimes hard to understand, even as we look directly at them. Shimoda writes,

A watermelon being sliced

Keeps the town alive

It is the being we depend on

Not what the being looks like

Here the watermelon is vital not because it’s a tasty snack and prettily red and green and white and light green, but because it is being sliced. As long as it is being sliced — as long as it is here, as long as it is watermelon — the town is kept alive. Watermelon is something “we” depend on, a reality “we” know by heart not sight. For me Evening Oracle truly sparked on my second read, when I asked it not what it could tell me about my life now, which is not really the way to read anyway, but what it already knows. What it can teach me. Evening Oracle knows a lot about old women, and men’s asses, expanding shapes like fog and fire, tiny pink flowers, grandparental sex lives, stupid angels, confusing tender family, and a box of deep-fried pork. All this knowledge is offered immediately and contextually locked into the anthropocene, dreamlike and rhizomatic, because “Facts are fake plants, the shape without the life, hard and made.” Everything we can know anything about is a being affected by space and time. This point of view fits a travel narrative and pillow book like Evening Oracle so well, for example the aforementioned box of deep-fried pork. Another poet might talk about pigs, might talk about smells and recipes; Shimoda talks about presence and desire:

I want to sit on this bench

With this box of deep-fried pork

And eat the deep-fried pork out

Of the box

Forever

Sure, in some ways this desire is childlike but that doesn’t mean it’s foolish, and more importantly more beautifully, I think, it allows different kinds of time to exist in the book at once. Shimoda is writing poems in bed at night, but he is also eating deep fried pork forever. Best of all the epiphenomenal time here isn’t cutesy — it’s deeply sincere. “I can feel my vagrant idiocy,” Shimoda writes in neat rhyme, “Mistranslating those / unrelated to me / I visit still, repeatedly.”

And he’s not alone. While the reader never doubts Shimoda’s light up ahead (or behind, or sideways) on the trail, we listen too to his friends and family in letters to and from him. There are excerpts here from walks and other kinds of correspondence with Etel Adnan, Mary Ruefle, Brenda Iijima, Don Mee Choi, Phil Cordelli, and especially the poet Dot Devota, in addition to signs, languages, colors, and tastes from Shimoda’s travels across Japan. Presumably these treasures are linked in geography and time. Other connections, smartly, aren’t forced but come to the surface naturally — plants and breath and fruits, and food other people prepared lovingly, and most especially the mortality of parents still living and long gone. Shimoda I think maps this last territory especially accurately. How do we find family — how do we know family — we’ve only met in stories and genetics? How are we part of a lineage when we are writers, traveling without biological children but holding deep love anyway?

Rob Schlegel writes, to Shimoda and we overhear them, if “you think we’ll all turn round when we die, like grapefruit, to be dipped into the sea’s radiant glow . . . ” I love how “round” echoes: in the shape of citrus, in looking over your shoulder to check direction or for company, in the repetition of sound. Evening Oracle as a whole does this too, and is best read in chorus with Shimoda’s earlier O Bon, also designed by HR Hegnauer; Prince Niu’s poem “An elegy on the death of Prince Iwata,” where this book gets its name; Dot Devota’s poems; whatever grief you the reader carry; and perhaps too Williams’s Paterson, as an early map that Shimoda soon and elegantly took offroad. I loved this book and am excited to read it a third time soon, then again and again.

Mairead Case is a working writer in Colorado, where she is a doctoral student at the University of Denver, Coordinator at the Naropa Summer Writing Program, and a poetry teacher at the women’s jail. She is the author of the novel See You In the Morning (featherproof) and the poetry chapbook Tenderness (Meekling Press).

This post may contain affiliate links.