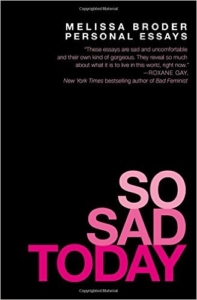

[Grand Central Publishing; 2016]

[Grand Central Publishing; 2016]

tw: depression, anxiety

The first time I quoted a tweet by @sosadtoday (the once anonymous account that poet Melissa Broder started as a way to deal with her anxiety and depression) in an everyday conversation, I felt brazen and very weird. I spoke the tweet out loud to a friend (“gentle reminder that i never asked to be born”) and thought “You’re someone who live-speaks tweets now. Another burned bridge.”

Similarly, I’ve started texting people selections from Broder’s eponymous collection of essays So Sad Today. My favorite quote so far: “Well meaning people can save me from myself, but they cannot save me from being alive. Only my god can do that. Sometimes my god speaks through well meaning people. Sometimes I am so lonely.” Texting a person a quote from another person about your own loneliness strikes me as the most millennial thing, but maybe that’s just because it’s delivered in a puffy blue text bubble, like most of the things that matter to me.

One of the shittiest things about being chronically, severely depressed is the eventual realization that my suffering is neither fully mine nor fully escapable. This knowledge — and how I feel about it — flickers in and out depending on where I’m at. If I’m sleeping okay, out of bed during daylight, returning a friend’s texts within at least a few hours (we all have shit we’re bad at), then I’m pretty fine with understanding my depression as a structure: a place where the mirrors are the floors and your face doesn’t belong to you and everyone else there is invisible and not doing a great job of figuring it all out, either. But when my feet are pressed down on a floor that just makes more feet and I can’t remember where my eyes are and every potential text becomes a threat (if I don’t respond then they will think I don’t care or maybe they’ll think I’m so functional that I’m busy and happy or if I do respond then that’s too fucking close — they cannot know what this is like right now, please don’t look), then the idea that this badness is laughably un-unique strikes me as such an insult — an insult against my ego, suggesting that my suffering must refuse replication in order to be meaningful. And if it’s not, it is my own fucking fault. Next time I’m there, I know I’ll think that. Right now, that scares me.

Each fear has its particular landscape, and we have plotted mappings of them now. Did you hear the one about the guy who was wearing a FitBit while his heart broke? It came up on my Apple News for days. Everyone was super into it — the FitBit recorded his heart rate spiking, going for broke, settling back into itself. You know the feeling but feelings are ineffable — and heartbreak is classed among the “I was so afraid this would happen, it’s happening and I’m still afraid” fears, alongside absolutely eating it on the sidewalk and giving birth (I assume). We like feelings when we can print them out, if only because it’s that much easier to pick over the scabs. That’s why I like Twitter.

I have my own set of anxieties around Twitter. It materializes my more nebulous fears of never saying the right thing, never being funny enough, never making enough full grown men feel bad about themselves, never striking into the wet acrid heart of humanity with my steel-tipped intellect. In its best moments, Twitter can facilitate the uncomfortable but so completely necessary exchange of reflections, accountability, and learning, but I’m mostly just there to watch. My own Twitter is a smattering: retweets from an account from a bear’s POV, love pleas for Neil DeGrasse Tyson (please be my cosmic husband, etc), bitching and moaning about my dissertation. I’m a big retweeter.

But, true to the little mirror box that coils my small joys back in on themselves, I almost never engage with the things I love the most on Twitter. Even faving a tweet sometimes requires me to beat back a mini-chorus of judgey fucks. This happens all the damn time with Broder’s @sosadtoday. Her shit is just too much my shit, but it’s also completely her shit — the mirror made more feet, but they’re her feet, too! My little brain reels. “learned to love myself jk”; “this too shall pass and come back resistant to therapy”; “am i allowed to be okay?” So many of her feet dancing behind the mirror with my feet. I tweeted to her once that her work made me feel lazy. She faved it. It was so great.

Because the loud majority of @sosadtoday’s followers don’t seem to have my massive tweet-angst, the account gets thousands upon thousands of retweets and faves everyday. And in keeping with her popularity, the essays in So Sad Today spin endlessly outward and inward from her Twitter. If the cartographic method of the @sosadtoday account most closely resembles daily blips from an underground sonar, then the book So Sad Today leaves the subterranean behind, and exposes Broder’s own relief map of phobias, fetishes, despairs, and intoxications.

@sosadtoday’s signature tone — sarcasm to the point of recklessness, confessions delivered from TweetDeck — is all over these essays. What I like about this tone is how much it fails, and how often Broder explicitly comments on its failure, beating you to the punch so you don’t judge her for something she’s making it clear that she’s aware of. “I Don’t Feel Bad About My Neck” is the most concrete example: Broder explains over and over again how it’s shitty enough to feel pain you aren’t able to account for, but communicating that pain is both independent from larger apparatuses of human suffering — transphobia, police brutality, white supremacy — and dependent on acknowledging that those matrixes persist, always: “Is there a difference between being supportive of other people’s revolutions vs. turning something tragic into your own experience? I think there is.” Depression is a form of distance from collectivity and accountability to the collective. Sometimes more feet on the floor are just more feet.

“Google Hangout with My Higher Self” makes it clear that gchat grammar and taste performance are a pretty perfect way to make self-regard an intangible joke — a little bit of pathos, lmao.

Me: i feel like i’m not good

Higher self: gurl u r good

Higher self: u contain———>infinite goodness

Me: idk

In “Google Hangout,” Broder is as afraid of the potential “light” of betterness as she is of her more well-known agonies (“Me: what if i get addicted to the light? Higher Self: guuuuuurl”). Being healthy — in whatever iteration — is too often characterized for us as a quietness, a humming glow in which there’s no need for rumination — the detachment between your beautiful healthy self and the things that make it so is perfectly complete. Reams of self-chatter are discouraged, signs of disease. Classifying the severe, cyclical depression that erases my sense of emotional proportion and makes comforting conversation almost impossible as an “illness” makes sense to me, but the word “disease” works even better. I am ill, I am “dis-eased.” But this has been going on for so long that it’s hard to tell the difference between the depression and what it touches — have I ever possessed an “ease”? I couldn’t stop thinking about this as I was reading So Sad Today — we are never, and never have been, innately clean, pure, purely “at ease.” Does it matter so much if I can’t place my finger on the very first fault line between my ease, and my illness? (The self on the other end of my gchat: i dunno bb).

I don’t want you to think that reading this book made me feel good. For Broder, the term “good” veers from obscure to ineffectual to sometimes completely obsolete. Anxiety redefines these words, and then tries as hard as it can to hide its redefinitions. In the essay “Keep Your Friends Close but Your Anxiety Closer,” Broder articulates the logic of functionality that her panic disorder imposes on her own interiority, and her subsequent scrambling to control how she might be legible to other people:

Recently, a woman said she likes my writing because I’m not a whiny cunt. I think what she means is that she likes my funny mask. But now, the panic attacks are stripping me of my ability not to be a whiny cunt. I want to be in control of my whiny cunt levels! If I’m going to alienate you, I want to curate that alienation. I want to craft the persona that turns you off.

You don’t want to be disliked. You don’t have the luxury. If it is sometimes inevitable, does it hurt less if the dislike is aimed at that something in you that you’ve already called out as shitty? Total invulnerability is impossible. We blip along, and invulnerability slides into “weird” slides into “okay” slides into “sad today” slides into “jk.” Look behind the curtain, it’s filled with raindrop emojis and pith. I liked this book.

G. Brown lives in Buffalo, NY and won’t fave your tweets.

This post may contain affiliate links.