In their introduction to City by City: Dispatches from the American Metropolis, co-editors Stephen Squibb and Keith Gessen describe the subsequent collection of essays as taking place “between the day of the Lehmann bankruptcy and the shooting of Michael Brown.” The pairing suggests a freshly minted historical moment in which the finance economy, race and police brutality in America are intricately linked. Their bracket makes sense: these two events spawned our nation’s largest, most visible dissident movements in a generation, Occupy and Black Lives Matter.

Gessen is a founding member of the Brooklyn-based literary magazine n+1, which partnered with Faber and Faber to publish the book. Originally conceived as an exploration of the “political and economic fallout of the financial collapse in cities across the country,” its scope expanded when “the cities themselves erupted.” The seismic invocation is a reference to the sudden ascent of Occupy Wall Street (OWS) to a national, then global phenomenon. Around this time, n+1 began circulating a semi-regular gazette entitled Occupy!, which featured a series of gonzo-style dispatches on the movement and its many incarnations. On November 15, 2011, New York City police forcibly removed the Occupiers from Zuccotti Park. Two days later, Gessen himself was arrested. He wrote afterwards in The New Yorker that, at the time, he’d been participating in a “‘direct action’ meant to paralyze, or at least impede the smooth functioning of the New York Stock Exchange.”

From its inception, n+1 has been conscientious about the tension between theory and action. It is also aware of what a double-edged sword its geographic and demographic insularity can be. On the one hand, the magazine has built a strong coalition of intellectuals, activists and artists with shared socio-political concerns — a mark of distinction in contemporary America’s vapid political landscape. On the other, its presumed New York hermeticism and intellectual loftiness, along with an erudite in-house register that exudes and assumes a high level of contemporary cultural capital, together reflect the magazine’s inability to attract a broader geographical and class readership. (n+1’s sports commentary, for example, seems not so much an attempt to make n+1 appealing to the masses as to make the masses appealing to n+1. In a report on the NFL’s PR crisis concerning the preponderance of concussions and other life-threatening and/or career-ending injuries, Squibb writes with histrionic precision that “Knees break more frequently when these vast territories of muscle careen into one another, ligaments snapping like guitar strings as giant torsos collide wildly above them.”)

City by City is in part an attempt to rectify those concerns. “We had learned the view of the crisis from the office towers of Manhattan,” write the editors, “we wanted a view that was a little more from below.” And in that regard the book is a success. At worst, it can sometimes be guilty of a species of hyper self-conscious native tourism, but at best it elucidates and works to humanize real social and economic injustices. Its geographical breadth is substantial, and New York City itself is rarely mentioned. In fact, there appears to have been a concerted effort to minimize its hovering influence over the collection. Looking at the supplemental map of the United States found within, which denotes only the cities under review, there is a little dot where New York City should be that just says “Brooklyn.” But perhaps that is where we should begin anyway, noting the irony that no matter how hard we might try to speak of anything different, we must always speak first of New York.

“Bed-Stuy” is nestled in the back of the book (34/37). It begins with Brandon Harris, the author and a self-described “light skinned Negro,” walking home in the affluent neighborhood of Clinton Hill, when a stranger holding a bludgeon starts to follow him at close range. Since Harris is not a fighter, and has a brand new MacBook in his bag, he becomes increasingly nervous, and so breaks into a run to reach his apartment at 227-241 Taaffe Place. Likewise pursued, Harris smashes the entrance door on the would-be assailant’s arm multiple times. His plot foiled, the teary-eyed stranger yells, “This is Bed-Stuy, bitch!”

This confuses Harris. He was supposed to have been living in Clinton Hill with his obnoxiously affluent, casually racist white friend. Since when was this Bed-Stuy? It’s hard for him to say. The boundaries are always shifting.

Brandon Harris, like many young members of the “creative class” in gentrifying cities, is at once an agent and a victim of his changing environment. Although he struggled to pay rent for the duration of his time at Taafe Place, he “wasn’t deluded enough to think that lofts inhabited by kids with mysteriously inexhaustible checking accounts and spliff-smoking wannabe filmmakers had always existed” there. Nonetheless, in time the rent truly does become too much. To save money, he opts to relocate even deeper into the neighborhood, “one of the poorest zip codes in the borough . . . dominated by a series of decaying row houses and brick walk-ups filled with immigrants from the Western Hemisphere’s most impoverished countries.”

Brandon Harris’ dilemma is not just a matter of race, but also of class, and more specifically of the so-called creative class. As an African-American filmmaker, he is acutely aware of the influence his dilapidated surroundings have had on a film and music tradition he admires. Speaking of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, Harris says:

The busy and bustling community depicted in that film was a fantasy. Which is not to [say] those early Lee films don’t represent a certain reality of the place. But it was a vision of Bed-Stuy as much less poor and desperate and sad than it actually must have been in those years, a Bed-Stuy that was more like the liberal, middle-class neighborhood where Lee himself grew up: Fort Greene.

Later, Harris notes that Notorious B.I.G. was raised in Clinton Hill.

It was Biggie’s great achievement in his remarkably dexterous lyrics to express this other kind of double consciousness. The songs are rife with tales of Bed-Stuy violence and social decay, even as Biggie clearly yearns for a different kind of world — one that he claims to have already reached by robbing and drug dealing but actually hopes to reach through his art.

Analogies abound. Lee, Biggie, Harris — each in their own way struggles to arrive at a certain ‘acceptable’ level of authenticity, in their lives and in their art, vis-à-vis the city. For them, Bed-Stuy inspires awe and contempt simultaneously, and its magnificent squalor has the power both to free the muse and to blind it. This emerging dialectic between artistic opportunity and contested space will be familiar to most readers of City by City.

***

By this stage in the book, urban theorist Richard Florida has become a constant presence; his name doesn’t need to be mentioned in order to be evoked, though it is mentioned often. In an essay on Boise’s unanticipated turnaround from a cultural backwater to a reasonably tolerable place, Ryann Liebenthal writes, “though I am somewhat loathe to admit it, the Boise renaissance owes at least part of its instantiation to Richard Florida.” In their interview with Gar Alperovitz, a workers’ co-op activist in Cleveland, n+1 asks Alperovitz what he thinks of Florida, a question for which Alperovitz requires only two words: “Not much.” The interviewer neatly reframes: “I mean, what function does he serve?”

In her essay on El Paso, Debbie Nathan writes: “According to Florida, struggling American cities could redeem themselves economically by attracting young gays, bohemians, and Silicon Valley types who seek diversity, tolerance, nightlife, and fun on the streets.” When this concept was first outlined in Florida’s Rise of the Creative Class (2002) it garnered much attention and endorsement. But a backlash ensued that extended beyond academic scrutiny of his data. In attempting to revitalize their cities by attracting wealthy out-of-towners, municipalities would be ignoring existent social concerns, preferring rather to simply uproot problem communities. Critics of Rise of the Creative Class (and of New Urbanism in general) argue that the text ignores persistent race and class struggles in pursuit of utopian cities designed for the privileged few, at the expense of the many.

But Florida’s ideas were never praised because they were revolutionary. They were praised because they were feasible. It is this very feasibility that makes them so attractive to some, and so dangerous to others. Even those of us who disapprove of Florida’s ideas (if not their core, then their scope) are bound to want to live in the kinds of urban spaces he envisions. And that’s fine: the problem is not bars, bike lanes and good coffee. The problem, rather, is that liberal impatience for urban amenities too often overrules our desire for better and more inclusive manifestations of good government.

The Floridian model is the spatial equivalent of trickle-down economics: the wealthy’s renewed interest in crumbling inner cities is said to result in the economic betterment of entire populations. And since the wealthy have the means, power and influence to get things built, the thinking goes, why not let them build? The offense of the creative class is that it believes its self-ascribed qualities of “diversity” and “tolerance” will naturally give way to more accessible and democratic cities for everyone. What’s obscured by this sunny narrative is that poor locals are often not financially capable of hanging in there long enough to see the end of the regeneration process, and where they end up tends not to matter very much — just so long as they’re gone.

In this respect, the most salient essay in the book is “Atlanta’s BeltLine Meets the Voters” by Alex Sayf Cummings. He describes a sprawling Atlanta, wherein a complex of walkable neighborhoods and downtown-like areas is circumscribed by the beltway of I-285. The suburbs outside the beltway span an area 10 counties strong, each of which is its own distinct municipality. Consequently, in the face of “a long-standing allergy to all things public,” Atlanta has suffered persistent and worsening traffic congestion for the past four decades. Cummings concludes, “If Atlanta is not America’s least walkable city, it is close.”

Things only began to change in the year 2000, when Georgia Tech student Ryan Gravel disseminated his master’s thesis to an unspecified bevy of “influential Atlantans.” The thesis outlined a proposal for a massive public works project called BeltLine, “an ambitious plan to build a ring of parks, bike paths, and ultimately light-rail around the city’s in-town neighborhoods.” The proposal immediately became the apple of Atlanta’s eye. Elected officials, banks and “private financiers” were all prepared to do their part. Save for the inevitable Tea Partiers, even the public approved.

The planning and early construction phases went off without a hitch. But in 2012, a one-cent sales tax referendum was proposed in hopes of raising $8 billion of public money for the project. This sparked a contentious debate and an increased level of scrutiny. Why were the poor being asked to pay for a rich-man’s playground? Why were funds previously earmarked for education now being put towards urban renewal? What other surprises were in store for the people? Cummings summarizes the liberal argument thus: “BeltLine will foster rising property values along its path, [accelerating] a process that has already transformed in-town neighborhoods [into] havens for the white middle class.”

He goes on to describe these concerns as “legitimate, albeit frustratingly complex. . . [the gentrification issue] emerges pretty much any time projects to improve quality of life in cities threaten to actually improve the quality of life.” For its part, the city’s response to growing dissent was to guarantee some degree of affordable housing where the BeltLine was predicted to raise property values (i.e. wherever it went). At-risk citizens are weary of promises though, having had such carrots dangled before them in the past: first in the 1950s when low-income neighborhoods were razed to make way for Eisenhower’s interstates, then again in the lead-up to the 1996 Olympics. Both times, promised reparations were completely insufficient. When the interstates led to the demolition of low-income neighborhoods, too few housing units were built to replace them, and the ones that were ended up being torn down for the games, “cleansing [Downtown] of its pesky black citizens (both housed and homeless).” Cummings cites Robert Bullard, a former professor at Atlanta University: “To have people who promote the BeltLine say, ‘Trust me, we’re going to do it right this time’ — I don’t see anything in past experiences that would somehow allow African Americans and people who are transit-dependent to say that we trust you to do the right thing this time.”

Cummings’ position is that doing something is better than doing nothing. BeltLine is the first major public works project to have any legs in Atlanta in over forty years; who knows when the next chance will be? His argument is studied and fair. It delves adeptly into the shameful history of American urban planning, and it is hard to disagree with his central premise that BeltLine will reduce traffic, and in the process make central Atlanta a greener and sprucer place. Still, he can’t escape from the “material realities” of New Urbanism: “Some will benefit more than others, and some may even be hurt.” The homeless in particular “will clearly not benefit.”

But then again, the BeltLine is not the cause of homelessness, and it did not create the insane American system of property taxation that makes safe neighborhoods with access to grocery stores, decent schools, and other “amenities” inaccessible to many of the urban poor and working class. Renters are subject to rising rents, and even working-class homeowners find themselves shuffled around according to the whims of people with greater means…To pin all these broader problems on the BeltLine seems wrongheaded if we really want to reduce traffic, increase density, and promote a future with fewer cars — for everyone.

In an otherwise parsing essay, Cummings underestimates the fact that our institutional neglect for minorities and the poor preceded our epiphany that fossil fuels are bad. In his defense he will say how “frustrating” it is that “environmentalists, civil rights activists, and advocates for the working poor cannot agree on an agenda for remaking Atlanta’s clogged, choked landscape.” And while this may be a frustration that is shared, he fails to recognize that racial, class and environmental agendas did not all arise from the same primordial soup of liberalism; he takes for granted the teleological, platonic togetherness of three highly distinct political constituencies.

We can’t fault him for speaking directly to Atlanta’s specific political climate, but his assertions have wider implications. They weigh the scales of utilitarianism, address postulated effects rather than root causes, and seek to persuade that projects such as the BeltLine are politically safe and ultimately good. Yet his equation glaringly lacks any further analysis of the culture of mistrust described by his own sources. Instead what it does is show that the working poor and African-Americans may have as much to fear from environmentalists as they do from fiscal conservatives. (“I didn’t go for Goldwater any more than Johnson” remarked Malcom X on more than one occasion “except that in a wolf’s den, I’d always known exactly where I stood.”)

Cummings does well to put “amenities” in quotation marks, highlighting the absurdity of our government’s interpretation of needs and wants. But when it comes to public housing, he suggests only that the promises to build (and ostensibly sustain) a sufficient number of units “ought to be monitored as vigilantly as possible.” This proposal is vague to the point of meaninglessness, particularly when his own research points to a systemic pattern of municipal refusal to commit to government subsidized housing in Atlanta.

Cummings’s breezy dismissal of the crucial housing question aside, this remains an essential essay, to both City by City and the broader conversation surrounding gentrification. The difficult balance we must strike between realpolitik and idealism is captured on every level — from the specifics and vagaries of policy to the ambivalence of the privileged liberal class — and in the context of n+1’s specific brand of double-consciousness, this is enlightening work.

***

I want to return to Gar Alperovitz now. “The Cleveland Model” is the 19th piece in the book — before “Atlanta’s Voters Meet the Beltline” — and the first interview. By this point we’ve seen financial collapse in Seattle, histories of the office and the interstate, immigration in El Paso and socialism in Milwaukee, to name a few. There have been a few laughs, and a lot of introspection. “Dallas and the Park Cities” is an exceptionally poignant recollection of growing up strange in the South. Some essays do miss the mark, though, and the book occasionally feels like a hodgepodge of lesser-known facts and learned noticing, rhetorically tempered by the economic and spiritual poverty of other people’s lives.

In terms of capturing anguish, one of the best is “The Kindness of Strangers in New Orleans” by Moira Donegan. The title is meant to be ironic: Donegan explores how post-Katrina volunteerism quickly became a pretext for moving in permanently. This tragic voyeurism creeps its way into her sentences, which have the capacity to incite repulsion and morbid fascination simultaneously. Because of the makeup of the Louisiana’s soil, we learn, when you bury a corpse in the city “it can eventually pop up again, like a beach ball pushed under the surface of a pool.” In a similar vein, Jordan Kisner writes that while San Diego is pleasant for most of the year, “when the Santa Ana winds come . . . the desert air sweeps back toward the coast, flooding the shoreline with air so dry and abrasive it feels as if it could light matches. You wake up in the morning, and the world feels thirsty and vaguely murderous. Your skin knows in a way your brain doesn’t that something isn’t right.”

Perhaps, we think, the best thing to do with our cities is drive through them, stock up on gas and rations if necessary, and continue on forever in a Mad Maxian mania, or at least until we reach a foreign country. Montreal sounds good. The Frenchness of abrupt social upheaval is encouraging, and besides, if it gets too lonely or too cold, it’s only 370 miles away from New York City.

“The Cleveland Model” gives the first hint that something might actually be done. Alperovitz reminds me a little of Raymond Williams in Politics and Letters: serious, declarative, not prepared to compromise ideologically or debate his fundamental premises. For most of us, if we were to draw a line graph that showed how the strength of our political convictions changed over time, we would start low, reach our peak in adolescence or early adulthood, then slowly drift towards moderation — or the line might just stop, disappear, signifying apathy until death. My guess is that Alperovitz, age 79, started where most people peak and just went straight, like a MiG at cruising altitude. He has the urgency of a young activist but treads like an elder statesman. Also like Williams, he’s a working-class bred intellectual, the socialist equivalent of a left-handed pitcher who can also hit.

Alperovitz’s political temperament is aggressively pragmatic, and in this way there is something effortlessly conciliatory about him. Alperovitz is like the IT guy who can tell you objectively which wires should connect and which ones are causing trouble. A recent interview with the New York Times is emblematic of this posture. In it, he notes the existence of programs in Texas and Alaska in which publicly owned oil and natural gas revenue is being used to subsidize the education and health sectors, and in some cases to put money directly into people’s pockets. On first glance it appears to be an ideological paradox, but one of the reasons these programs are viable is because they allow Republicans to keep taxes low. And while the more ecologically conscientious among us may be suspicious of fossil fuel extraction in general, the democratization of the energy industry (or any industry for that matter) is nothing to be sneezed at.

Neither is Alperovitz in favor of overnight proletarian revolution:

You know in the radical revolution context, collapse would probably go to the Right, not the Left. I spend a lot of time thinking about the emerging context. The emerging stagnating context of “neither collapse nor reform” allows for time to learn something new. You wouldn’t know how to run the system today if you were to take it over.

He advocates urban reconstruction instead. The areas where he sees the most opportunity are communities with existing and successful “anchor institutions” such as museums, government buildings, hospitals and universities. These are heavily used and publicly financed, meaning they can’t easily relocate, as private institutions so often do. In the course of the interview, he elaborates on his ideas about forming worker co-ops, which can feed off and contribute back to anchor institutions, thereby creating new, wholly democratic institutions in which the worker and the means of production are reunited and entrenched.

Alperovitz rejects the notion that workers’ co-ops are a panacea. “Elements, not solutions,” he emphasizes, adding “In highly gentrified cities this is not going to happen. . .in cities where the gentry is moving in, young people, people without families, you just don’t have the political economic preconditions to attempt something like this.”

(It is significant, also odd, that such a formulation would occur only five essays before Cummings’ critique of the anti-gentrification bloc. As a result, about halfway through the book we begin to sense a conflict between the editors’ political leanings and their desire to entertain a broad-ish spectrum of opinion. It is a legitimate break in the Left, but a less desirable one in a collection loosely collated around the idea that we are in need of some kind of substantive reform.)

For Alperovitz, workers’ co-ops can be culturally transformative as well. As feasible initiatives that produce tangible results, they are capable of reintroducing social-democratic thought into a society which has long been conditioned to believe that Marxism, socialism and Stalinism are not only interchangeable, but uniformly antithetical to Western ideals of democracy and pluralism. A co-op, he writes,

“introduces the democratization of wealth, and it introduces a planning model…And that’s very interesting, because you could do essentially the same thing at scale with, say, national mass-transit production when the next General Motors goes down.”

It is one of the ironies of the free market that when a manufacturing plant shuts down, a sufficiently organized and financed group of workers can buy it right back, taking for the people that which the market abandoned. They don’t have to be socialists, either; all they require is an understanding that when one door has closed, others have opened.

n+1: What happened in Youngstown?

GA: Youngstown was fortuitous. It was the first major plant closing in modern American history. Or at least the first one that got major publicity. Five thousand people lost their jobs. It was national news. September 1977. Big news, national. Now it happens all the time; it’s not news.

[The steelworkers] were saying “Let’s take over this mill,” and “Why can’t we run it?” And a deeply concerned ecumenical coalition got together and also said, “What are we going to do?” This was a really big crisis in the community.

…I helped them shape the idea that they could go forward with a worker-community ownership model. Just buy the plant and run it as a community. And second, I urged that if we dramatized it nationally —politically dramatized it, get the national religious coalitions and so forth behind it — it could be a big enough story that they might well pull it off. And even if you didn’t pull it off — this is what I liked about them — you would at least spread the idea. Which they did.

At the time political fortunes were good: the community even succeeded in obtaining a pledge from the Carter administration for somewhere between $100-200 million in loan guarantees. But then Reagan happened, and “the money disappeared.”

Although the plan ultimately failed, Youngstown turned out to be a model for others. Today, Cleveland has three such co-ops: Evergreen Cooperative Laundry [ECL], Evergreen Energy and Green City Growers. The environmental bent is unmistakable. ECL “capitalizes on the expanding demand for laundry services from the health-care sector, something like 18 percent of the national GDP” and uses only 8/10ths of a gallon of water per pound of laundry (far below the industry standard); Evergreen Energy installs solar panels on publicly owned buildings; and Green City Growers is a year-round hydroponic greenhouse.

What is striking here is focus and scope. These are attempts to lift up rather than relocate vulnerable communities, to stabilize rather than remind them they have no voice in political or economic society, never have and never will. These initiatives also work to set an important precedent: it will be the poor and the perennially disenfranchised who set this century’s environmental agenda — not the wealthy, not the ones who have created and contributed the most to the problem, nor those who continue to profit from the problem.

Co-ops may not be the definitive answer, but they are representative of what the answer should look like. Whereas projects like the BeltLine offer the upper and middle classes an opportunity to stop driving, a workers’ co-op offers the working class the opportunity to start thriving, and to become politically active. Whereas BeltLine has proven itself capable of alienating substantial segments of the population, workers’ co-ops have proven themselves capable of uniting social conservatives with unionized labor, and blue-collar workers with the communities they provide for.

***

Reading City by City, I was often reminded of the Frenchman Guy Debord, filmmaker, writer, theorist, founder of Situationist International (SI). The Situationists believed that by transecting Paris at night, on foot and drunk on wine, they were staging a radical protest against the capitalist order. The city had been built, they said, to keep the rich from the poor and the poor from the rich. There were places to work and places to consume, and then there was home. All life was a pale gray monotony. Geography mattered. To understand it outside of its relation to capital was to build the foundations of a new world order. A fusion of art and life was necessary.

In an essay for the London Review of Books, Hal Foster describes the “New Babylon” project by Constant Nieuwenhuys, an early inductee into SI. It modeled a post-revolutionary society that set “the future city of automation as a stage for nomadic movement and mass play, with high-tech elements refitted by residents like giant toys.” Nieuwenhuys envisioned this technologically advanced society as one liberated from work, for which the “fixed abode” had become a relic of the pre-revolutionary past. He called the citizen of New Babylon Homo Ludens, or “Man at Play.”

Or take Alexander Pasternak of OSA group, an avant-garde architectural association in the 1920s. In his brilliant book Militant Modernism, Owen Hatherley describes the group’s aesthetic shift from “induced” communalism to mobile cities. During the latter period, Pasternak wrote in OSA’s journal that the “fixed house was ‘an anachronism, apathetic and out of place, no longer an active participant in an active and fast moving life.’” Hatherley says the new designs illustrated houses that “were prefabricated, both easy for people to assemble and dismantle . . . to be provided by the state to individuals who could do whatever they liked with them.”

The unifying notion here seems to be that, since every individual harbors a latent artistic impulse, and the essence of the artistic impulse is the defiance of any kind of convention, then the city itself ought to defy convention. Hatherley comically illustrates this point when he cites the theorist Mikhail Okhitovich for his belief that “the right-angle was a remnant of the capitalist allocation of land.”

The Constructivist sheen of the prose belies a certain, prophetic reality. Today, neoliberalism seeks to imitate the left’s utopia — to pseudo-realize it by offering the creative class everything it has always wanted: the chance to thrive off its own ingenuity; for fun and work to become one (Google HQ instantly comes to mind); and to live in cities that never stop moving, or growing, or changing, or assembling, or disassembling. If radical communities have been swept into the dustbin, then radical mobility is much of what remains. Except it is not the radical mobility of the people that was once envisioned. Rather, it is the radical mobility of corporations, wages, housing, employment and ecological responsibility. For most, “nomadic wandering” is a symptom of disaster capitalism — whether economic or environmental — not the realization of a utopian schematic. We have only to look at the dubious demographic shifts behind “resurgences” in New Orleans and Detroit to know this.

The great prognosticator of The Possible, Richard Florida, encapsulates this new effort. In an interview with Jacobin, Florida says his decision to operate within the capitalist framework is merely a strategic maneuver, and that he comes at things “pretty much from a Marxist or neo-Marxian point of view”:

If Marx saw the working class as the universal class, I think the creative class — the notion that every human being is creative — is an even broader class. . .

When I talk about quality of place, I talk about quality of place for everyone. My critics can shape and twist this. But I’m talking about parks for everyone, green space for everyone, cities for everyone, cities that are diverse and open without regard to race and ethnicity, and how those things actually, ironically, propel development.

First, we note the old leftist conviction that everybody’s an artist, but refurbished to fit the new paradigm. Then we note the defensive posturing, in response to critics who have (erroneously, he insists) disparaged him as a neoliberal. So we resist the impulse to shape and twist. But we can’t help but note the details, the subtle but all-important emphases. This is a conception of a city where only parks and “space” are public: empty space, limitless space, policed space, space that — since Occupy — is not legally recognized as being politically available, and for which we have been provided with no real alternative. Meanwhile, “development” remains private, and therefore subject to the ideals of the market. Housing, work, goods, services: these remain tenuous, disconnected, deliberately apolitical. Development may very well occur, but for whom?

Indeed, in other forums Florida has recognized the need for affordable housing in America. But there is no escaping that, in the haste to be conciliatory, he has stepped into the same mire as Cummings, in which the moral quandary posed by market housing is addressed, but repudiated on the grounds of political expediency. When Jacobin presses Florida on his plan’s gentrifying effects, he says that he “cautioned city leaders and the creative class to be well aware over [the] contestation over space.” The phrase “cautioned to be well aware” is entirely in keeping with Florida’s decision to make his ideas palatable to politicians, but it is also, again, virtually meaningless. How does one caution a “broader than universal” class, anyway?

The assumption here is that all we need to make the morally coherent decision on this subject is more awareness, and things will work themselves out. This is in no way unique to Florida. It seems that every time the topic of American cities is raised, gentrification is recognized, lamented, and summarily dismissed. I would contend that this is due to a commonly held belief that gentrification, while inexcusable, is an incorrigible symptom of a greater and more sinister system of disenfranchisement. What results is a nimbyism of the soul: disbelief in the responsibility of the individual when the forces at work are so great. Even if the larger system of disenfranchisement exists — and it most certainly does — to view it from the other end of the telescope is now more vital than ever.

As it stands, Florida’s vision is an illusory one. In it, liberty precedes equality and fraternity. The latter two are said to follow close behind, but the logic of the lie has been exposed time and time again. Like an obedient but clever child, left to its own devices unqualified liberty can only transgress. This is the moral of the story of neoliberal economics. At the present we are still tempted by its shimmer. Like a sensuous dream, though, the imagination has finally gone too far. The kiss was too long. Consciousness beckons. We can no longer accept that privately owned space will foment or allow to foment the political organization required to defeat the negative feedback loop imposed by climate change, greed, and institutional poverty.

This starts with ending support for projects and policies that encourage the undemocratic displacement of low-income people, including low wages, no wages, expensive housing, no housing, market sensitive housing and inequities in the quality of education. Direct actions like workers’ co-ops are auspicious beginnings. But in the interest of momentum, one would like to see publications like n+1 — culturally relevant, with an above average level of discourse, not only concerned with gentrification in their pages but geographically near to it as well — cease asking questions and begin the far more difficult work of articulating solutions.

City by City might best be read as a precursor of such a moment. Throughout, its contributors display an uncommon capacity to grasp and elucidate on the ambivalent role they play in their respective locales. However, only occasionally do they take on the task of deciding what to do about it. Given this is no simple achievement, particularly for any one individual or in any one essay (I myself have struggled wildly with it here), but in the course of these thirty-seven essays, behind all the wonderful storytelling, accompanying historicity and useful tidbits, one senses that an opportunity was missed. This book is a song for the American city — always entertaining, sometimes sad — but it is too infrequently a resolution. Its best moments occur when it provides glimmers of a genre that combines the two.

If the creative class is to get serious about ensuring that our cities are sources of liberty, organization and progress, that they should not only be green but also fair, then it must first account for basic human needs and basic human dignities. Far from setting back the environmental agenda, prioritizing these reforms will offer the left the coalition it wants and needs but doesn’t yet deserve.

As Florida points out, in the post-industrial economy “place itself has become the key social and economic organizing unit . . . it is place itself that supplants.” So let it be ours.

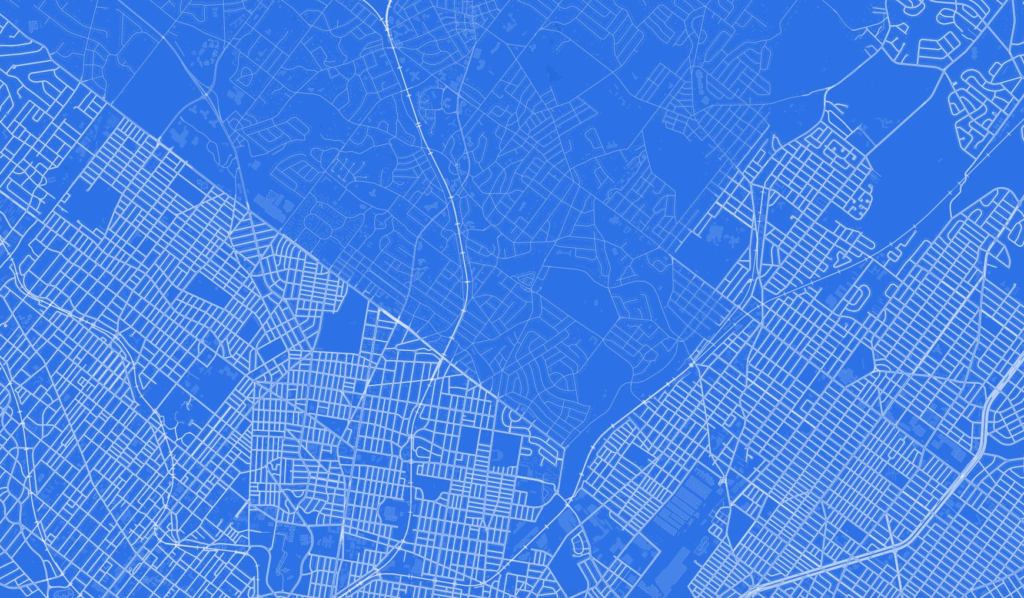

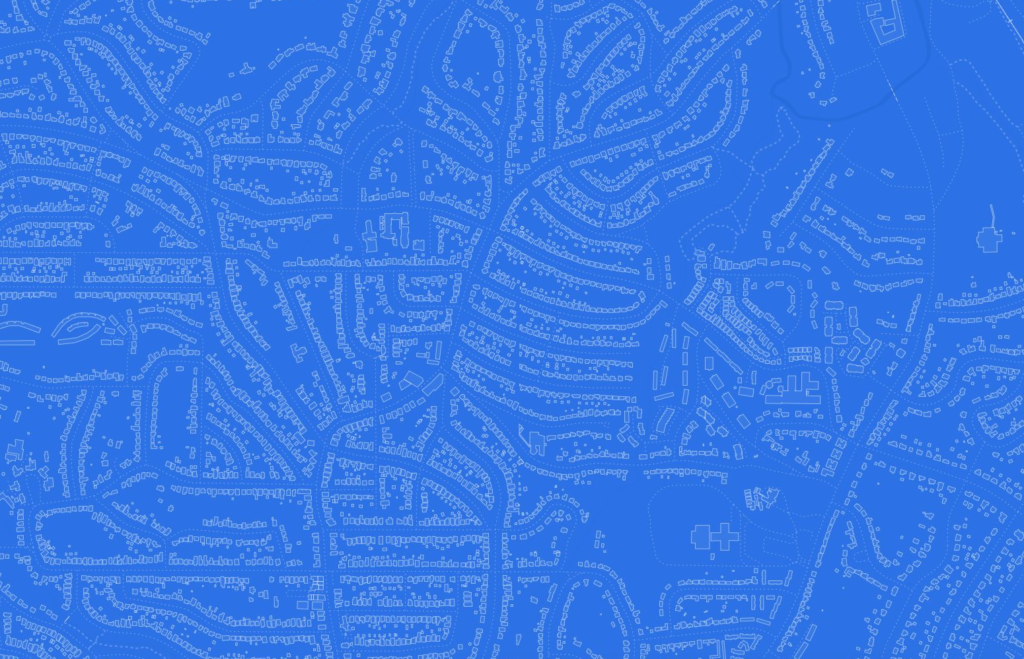

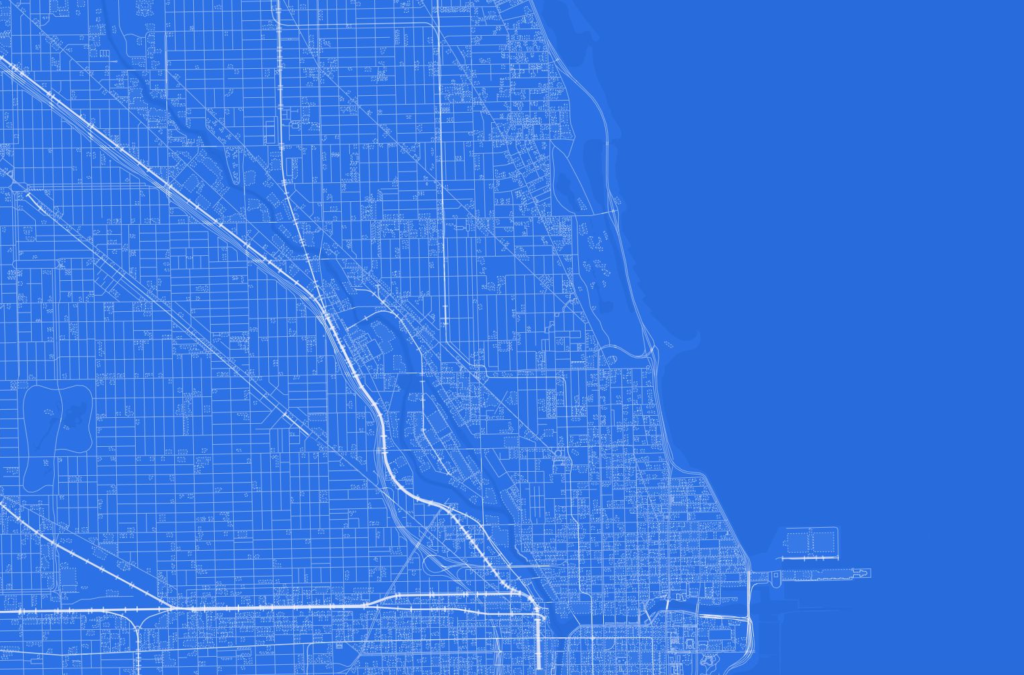

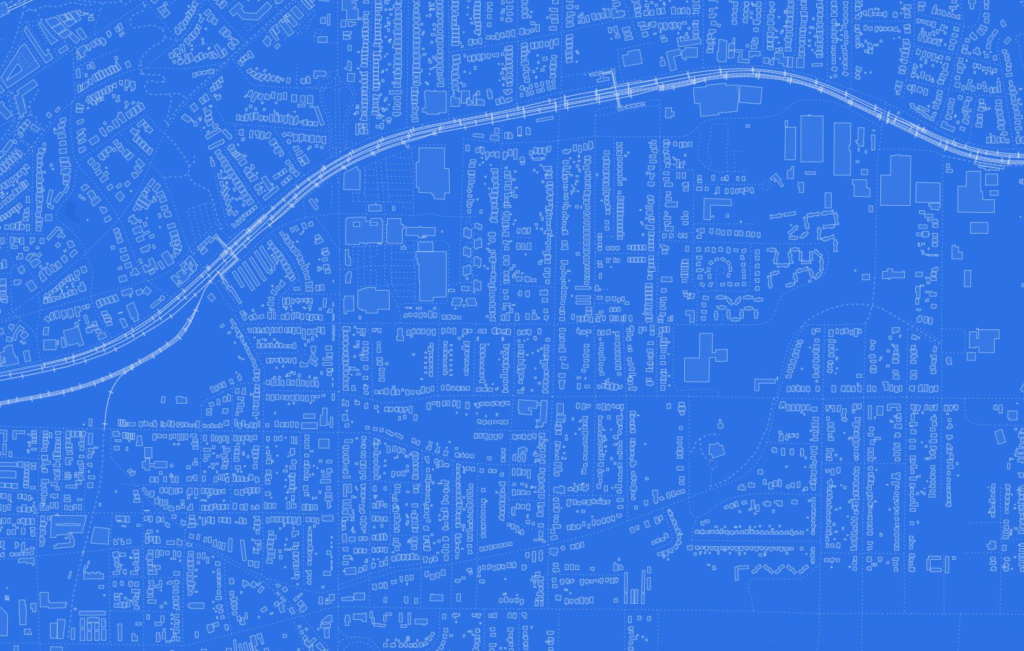

Images by Lauren Ancona (c) OpenStreetMap.

This post may contain affiliate links.