Tr. by Mitchell Abidor

La chair est triste, hélas! et j’ai lu tous les livres.

—Stephane Mallarmé

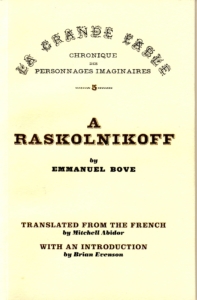

Unlike Mallarmé, I haven’t read all the books. Happily, this affords the occasional opportunity to encounter one like A Raskolnikoff and, with it, a writer like Emmanuel Bove (born the same year Mallarmé died, 1889), whom I’d somehow heard nothing of before stumbling onto a copy of the pocket-sized novella at the Small Press Book Fair at the Brooklyn Library in August. While there are obvious drawbacks to being ignorant, not having heard of Emmanuel Bove does afford one the opportunity to come into contact with writing quite unlike what one has hitherto read (granted of course one has opportunity to hear of and read Emmanuel Bove, for which I express gratitude to Mitchell Abidor for his wondrously estranged-English translation, Brian Evenson for his perceptive introduction, and Red Dust Books for publishing). To discover for oneself that such writing exists is, or was for me, to discover that there is at least one drastically different way to present narrative, and to be reminded that to alter the presentation is to alter the content. And so the story, the same story maybe, whether it be a story read or one that one tells oneself one is living, becomes not at all the same. The flesh, in other words, suddenly doesn’t seem so much sad as strange.

***

Although conceived in 1932 as an installment in a publisher’s series featuring contemporary authors resurrecting classical fictional characters, A Raskolnikoff isn’t just a newly-clad repetition of Crime and Punishment, at least no more so than your story or mine — the being born, the living, the dying — is a repetition of our mother’s or father’s. The eponymous Raskolnikoff of A Raskolnikoff — or one of them anyway — is named Changarnier and probably hasn’t killed anyone. If his angst mirrors that of Dostoevsky’s antihero, Bove renders it odd again. “He wasn’t thirsty and wanted to drink,” we’re told on page one. “He wasn’t hungry and wanted to eat.” A distorted mirror, neither quite parody nor homage to the opening paragraphs of Crime and Punishment, wherein Raskolnikoff has incurred an impossible debt with his landlord “not because he was cowardly or abject, quite the contrary; but for some time past he had been in an overstrained irritable condition, verging on hypochondria.” In a similar roundabout fashion, Changarnier reflects the erratic way Raskolnikoff interacts with others — one minute contemplating the murder of Alyona Ivanova, for instance, the next remarking, “how degrading this all is!” With comparable, albeit less lethal, fickleness, Changarnier welcomes Violette, his lover, into his home with a two-page-long harangue in which he brutally lays bear the already barely hidden sordid trappings of his worn and hapless commiserator:

“You’re not ashamed to be so wretchedly poor?” he said. “You’re not ashamed to inspire pity in all who know you? Don’t you have a shred of dignity in your heart? You live like an animal.”

To which Violette listens sadly, nods, cries, and agrees, because, as Bove rather brutally puts it, “When she took the trouble to reflect, what he had just said was also what she thought of herself. But normally, she preferred not to think.” At which point “something unexpected” occurs: Changarnier flip-flops:

On the contrary, you’re an angel. You pass through suffering and ugliness while keeping your heart intact. There is nothing more beautiful in all the world.

No, this is neither parody nor homage. The relation of A Raskolnikoff to Crime and Punishment is maybe most like that of a dream to waking life, or waking life to a dream. Some elements of one speak profoundly to elements of the latter, but these are different worlds.

***

In the pages that follow, we find dialogue equally grandiose and lachrymose, prose eerily deprived of the mundanity upon which our modern notions of mimesis and verisimilitude depend. This writing is deceptively simple, disquietingly precise, seemingly effortless, yet nearly, I’d imagine, impossible to replicate or imitate, for there are crucial realities here the writing is doing its utmost to convey, realities our realisms can’t confront, realities that require other aesthetics.

He understood that there was an immensity which he was not a part of, that no one was part of, and since no one was part of it, he understood that beneath the magnificent sky, on this overpopulated earth, it belonged to whoever knew how to get by.

Here is Bove getting by, navigating an immensity no one, himself included, can get a grip on, trying to say what is so damned difficult to say there’s no time for subtlety or verisimilitude. Translated and newly introduced into our show-don’t-tell aesthetic regime, Bove’s directness functions like an earthquake, reminding us of the fault-lines we’d forgotten we built our cities over, revealing the historicity and impermanence of our aesthetic ideals. We only thought we’d read every book.

***

“There are moments that are particularly beloved by the dissatisfied,” writes Bove, “transitory moments.” Violette and Changarnier flee from their unhappiness, and pursue an aimless path. “That’s it, walk,” Changarnier directs. “We have to go forward, we have to walk towards fortune and happiness since they aren’t coming to meet us.” Instead, the couple encounters only more turbulence. A “little man” accosts them outside a café they’ve been thrown out of, and insists on remaining with them. As a second and perhaps more literal Raskolnikoff, the little man is again, neither quite a satire nor a sympathetic reprisal of the figure of the tortured European Existentialist. As with the nature of Bove’s grappling with Dostoevsky in general, this appropriation remains entirely ambiguous, and yet seems startlingly consequential: “It was clear that this individual aspired to an air of dignity,” he says of the little man, “which made him somewhat ridiculous.” Despite Changarnier’s violent attempts to separate, the little man remains undeterred and manages to impart his story, a story which accounts for about a fifth of the novella’s pages, and features, however briefly, the book’s only attempts at narrating anything resembling happiness, an attempt the little man quickly qualifies with:

There’s nothing in the world that makes people as skeptical and is as difficult to revive for others as lost happiness . . . And yet I have to tell you that I have fallen short of reality, precisely so as not to fall into this trap, and if I wanted to depict it as it was I would be accused of exaggeration.

The precision and perceptivity here might make a reader suspect a similar sort of strategy at play in the novella’s aesthetics. Perhaps what’s at stake for this realism, like any realism, I suppose, isn’t the disclosure of any reality, but a connection maintained with the reader. The connection in this case, however, doesn’t seem to pertain to the suspension of the reader’s belief, but to our continuous surprise and sense of almost gleeful groundlessness. Like Changarnier and Violette, we have no choice but to continue on, walking through this alarming landscape.

It’s snowing, but the snow is white, light, and happy, like me. It’s falling harder, but instead of hiding the other world from us it’s announcing it.

Even if our path gets cold and bleak — adultery, abuse, murder, suffering, ugliness, etc. — it’s a bleakness all its own, a new book, different flesh, a heart intact. And, to echo Changarnier, there’s nothing more beautiful in all the world.

Jesse Kohn‘s fiction has appeared in Spork Press, Sleepingfish, The Atlas Review, Everyday Genius, SAND Journal, and elsewhere. He has contributed essays and interviews to 3:AM, The Rumpus, Quarterly Conversation, BOMB, Bookslut, HTMLGiant, and more. Links can be found here: http://jessekohn.weebly.com.

This post may contain affiliate links.