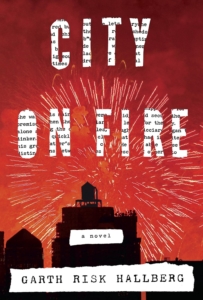

In this first novel set in the New York City of the late 1970s, a central artist character nails together a “four-by-four frame” and thinks “blame New York: he still had the conviction that American art should be Big.” City on Fire is big: 927 pages, a dozen substantial characters, numerous plots and subplots, all five boroughs represented, seven books and facsimile “interludes,” 94 chapters. And it has had big buildup: movie sale before publication, huge advance, pre-pub comparisons of Hallberg to world-class heavyweights.

A novelist in City on Fire has the Tristram Shandy problem: in the novelist’s “head, the book kept growing and growing in length and complexity, almost as if it had taken on the burden of supplanting real life, rather than evoking it. But how was it possible for a book to be as big as life? Such a book would have to allocate 30-odd pages for each hour spent living.” Regarding scale, Hallberg has mentioned his fondness for 19th-century triple-decker novels and for Bolaño’s 2666. He has eloquently defended DeLillo’s Underworld against James Wood. So I expect readers of Full Stop, especially those residing actually or notionally in NYC, will wonder if City on Fire is really “Big” like Underworld or other American novels of New York such as Gaddis’s J R or McElroy’s Women and Men or even Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge. Or if Hallberg’s novel is, in the famous words of Ed Sullivan, who hosted a TV variety program during the period the novel covers, a “really big show.”

At the core of City on Fire is a traditional dynastic plot: elderly plutocrat Stuart Hamilton-Sweeney owns a skyscraper with his name on it in Midtown. After the death of his wife, the gold-digger Felicia Gould and her crooked brother Amory worm their way into the failing patriarch’s firm and his family. The patriarch’s son William is a gay, drug-using, one-time punk musician, a painter and photographer who hasn’t spoken to his father or sister for years. In the present William is involved with a naïve African-American would-be novelist named Mercer Goodman just up from small-town Georgia. The patriarch’s daughter Regan, who does public relations for the firm, is married to money manager Keith Lamplighter, with whom she has two children. The Hamilton-Sweeney children’s lives cross at a squat in the Lower East Side, where William’s former band lives and where Keith begins an affair with a college-age groupie named Samantha. Will the Hamilton-Sweeney heirs accept responsibility and save the company from the Goulds and from an insider trading charge? And then can the building and family be saved from a bomb manufactured by the band that has, under the new leadership of Nietzsche-quoting Nicky Chaos, morphed into a radical anarchist group?

As an appetizer for the slow-cooking succession story, Hallberg early on introduces an attempted murder mystery when someone shoots Samantha in Central Park. Her weeks in a coma allow Hallberg to bring in her father, a fireworks contractor; her high school boyfriend from Long Island, Charlie Weisebarger; various misfits from the music and drug underworld; investigative journalist Richard Groskoph; his neighbor, the young gallery assistant Jenny Nguyen; and a crippled old police Inspector named Larry Pulaski. Eventually, the dynastic and murder plots come together and reach a literal cliff- (or skyscraper-) hanging climax on July 13, 1977, the night of the famous blackout.

The number of elements that Hallberg eventually unites is impressive, but City on Fire is essentially a traditional, even a formulaic work with a very long and high Freitag’s triangle. Compare the novel with one that Hallberg says he admires, Coover’s The Public Burning, which ends with Uncle Sam electrocuting the Rosenbergs in Times Square, and you will see the conventionality of City on Fire. Coover’s novel was an anthropological carnivalesque work with documentary features. Hallberg’s book presents itself as a sociological “documentary” with a moviesque ending. The interludes include handwritten pages by Stuart Hamilton-Sweeney, two typed sections of the journalist’s “Fireworkers” manuscript, too many illustrated pages of Samantha’s zine, a long letter from the patriarch’s grandson, and some photographs. The 96 short chapters usually focus on one or two characters and are heavily expository and narrative. As the stories move forward, the novel also moves backward with lengthy flashbacks to the earlier lives of the characters. They are sufficiently realistic (maybe too realistic, too familiar and recognizable) to support the documentary illusion, and the ‘70s mise en scene must have been heavily researched since Hallberg is only 39. But perhaps because his scale is so large, there is a paucity of dialogue and the drama it creates. In this regard, compare City on Fire with J R, which is almost all dialogue and trusts readers can follow complex relations without having their hands held by the author. J R seems more “documentary” — an oral history — than City on Fire, which is like an illustrated omniscient history. In his reviews and essays, Hallberg shows he knows modernist and postmodernist fiction, but in this novel’s plotting and character development, City on Fire could have been written by Dreiser had he lived long enough or Tom Wolfe had he damped down his style.

Hallberg’s “Note on Sources” mentions Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach and Gregory Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind. I was very surprised to find him crediting these two works that influenced my study of Big American novels of the 1970s and ‘80s entitled The Art of Excess. Surprised because the two works develop in great detail the importance of homology or analogy (form versus causality) as a means of creating conceptual systems and connecting disparate materials. Perhaps if I thought City on Fire mysterious enough to read again, I would find that Hallberg creates the kind of analogues that give, for example, Underworld, from its title onward, its original treatment of urban ecology, its inventive synecdoches and odd assemblages, crazed existential voices and potent abstractions. Hallberg knows DeLillo’s novel inside and out. But because Hallberg has chosen to commit himself to more accessible methods — old-fashioned character agency, plot causality, and documentary representation — City on Fire doesn’t provide a new and profound systemic understanding of the thick city that is its subject. Yes, Hallberg includes different meanings of fire — from fireworks in the sky to fire in the loins, from political arson to the fire of damnation — but for this kind of imagistic connectivity he didn’t need Hofstadter and Bateson — or DeLillo.

Given the number of pages Hallberg has written, it may be unfair to expect the kind of stylistic fire and variety we find in either McElroy’s Women and Men, which includes the voices of angels on high and of idiot savants on low city streets, or even the double-binding first-person banalities of Bob Slocum in Heller’s Something Happened. The sections of City on Fire that dip into the mind of Goodman the novelist are not so different stylistically from the sections about Regan the anxious mother or those that feature the teenage rebel Charlie. Different concerns, surely, but all expressed within a fairly narrow discursive range. McElroy and Heller, along with the other Big novelists of New York I’ve mentioned, felt, I believe, that the city as subject required some artistic deformation beyond mere supersizing — what I’ve called functional excess, formal and stylistic methods of defamiliarizing a place and people much depicted in every medium. Hallberg seems more interested in familiarizing his readers with the bad old days of New York City in the 1970s. Every year or two, the Times publishes a story about a person who has walked every street of Manhattan. In his prose, Hallberg is like that pedestrian until the final 120 pages when the blackout causes the pace to pick up and the style to rev up.

In 2011 I published an essay wondering why we didn’t have in the 21st century a New York novel that equaled those earlier works I’ve mentioned. The closest candidate was Colum McCann’s Let the Great World Spin. Since then Pynchon has released Bleeding Edge, but it was a long, sappy entertainment, no Gravity’s Rainbow of the Big Apple. The last few years have seen some ambitious and excellent novels set in New York — Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers, Atticus Lish’s Preparation for the Next Life, Siri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World — but none combine the comprehensive vision and artistic originality of the late 20th century works. So I was hoping for big things from City on Fire. It is certainly large and seems to this recent arrival in the city widely informed, but it’s that third dimension — depth — that I didn’t find. The novel has an ambitious (if ineffectual) novelist and an experimental artist, but the character who most closely approximates the sensibility of the author is a journalist.

City on Fire has numerous literary allusions and metafictional pointers, a reference to the Great American Novel, several mentions of that Great American Poet Whitman. The walls of the artist William’s studio represent the fiction that describes them. The walls are “covered in signs, the kind you saw on subway platforms, or taped to the bulletproof glass of a bodega. Something was slightly off about them . . . A stop-sign was skewed, its angles foreshortened. An Uncle Sam recruiting poster was taller than she [Jenny] was and missing an eye.” Observing this trompe l’oeil work, the gallerist Jenny “couldn’t tell if it was good, exactly, but no one could say it wasn’t ambitious.” The paintings are reminders, not inventions, facsimiles like the novel’s interludes. Hallberg’s characters and events are factsimiles.[sic] Like that part-time New York City resident Jonathan Franzen in Freedom and Purity, Hallberg offers reams of data about familiar people within a slightly fractured but eventually closed form. Unlike Franzen, Hallberg has at least attempted the Great New York Novel — “no one could say it wasn’t ambitious” — but Hallberg has placed too much trust in the throw-weight of his subject and his pages, so the “great” is less qualitative than quantitative, as in the phrase “the greater New York area.” A devotee of Excess, I’ve never used the phrase “less is more.” But fewer characters and plots might have given City on Fire more of the metaphoric density of The Flamethrowers or the emotional intensity of Preparation for the Next Life or the meta-artistic insight of The Blazing World. Now, take those three medium-length novels and jam them together, and you’d have a new Big Book of New York.

Tom LeClair is the author of three critical books, six novels, and hundreds of reviews and essays in national periodicals.

This post may contain affiliate links.