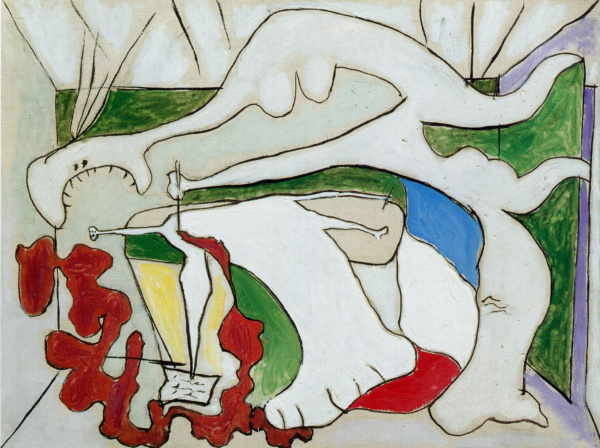

Woman with stiletto (Death of Marat), Picasso, 1931

Edward St. Aubyn’s Patrick Melrose novels received tremendous acclaim. They tell the saga of an affluent and abusive family, and the bildungsroman of Patrick Melrose growing at this hearth. The artful elegy was deserving of the rapture it received. Thus, it is no surprise that Picador is re-pressing St. Aubyn’s A Clue to the Exit (first released in Great Britain in 2000) for American audiences. But the novel’s decade and a half long hibernation speaks to a longer dormancy — namely, the seventy years since the death of the existentialist novel.

Like a thistledown caught in the winds of time, A Clue to the Exit’s premise seems to have floated to earth from the post-WWII era of Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. St. Aubyn’s titular allusion to Sartre’s 1944 play No Exit is not happenstance. The novel begins with the protagonist Charles Fairburn, a successful screenwriter, who discovers that he has six months to live. The rest of the novel is structured around how he handles his imminent demise — a decidedly existential framework.

But unlike the three hapless protagonists in Sartre’s No Exit — who spend the whole play confusedly discussing where they are — St. Aubyn’s protagonist knows exactly what he’s doing: After considering suicide for a brief moment, he decides on a more Dionysian path. “In a self-service world where you have to fill your own petrol tank, assess your own taxes, and help yourself to self-help, the one thing you don’t have to do for yourself is end your own life.” Selling off his possessions and heading casino, Charles is caustic and self-deprecating narrator, who mocks depression, suicide and redemption alike.

A Clue to the Exit’s most direct forbear is Leo Tolstoy’s 1886 The Death of Ivan Ilyich. Tolstoy’s novella, like St. Aubyn’s one hundred and thirty years later, opens with Ivan learning that his death is imminent. Ivan struggles to accept the news, attempting to reason with higher powers and growing furious with his destiny. Yet Ivan’s fate is one that we all ultimately share: death. Ivan’s premature end is fodder for a novella full of philosophical, emotional and religious contemplation.

Charles is has little interest in such reflection. He accepts his death sentence with a poker-faced determination: “the luxury of knowing when I was going to die, unknown to the athlete and the health-store freak, was surprisingly hard to give up.” He decides to move into a fancy hotel and squander his remaining assets at a casino. Crystal, his newly acquired lover, helps him to gamble away twenty-five million francs a day while sharing prurient adventures in their suite.

Antithetical to the existentialist rumination of yesteryear, Charles’s reckless abandon is further supplemented by his savvy agent, Arnie, who asks to be his executor upon hearing Charles’s diagnosis. A death sentence is no longer a reason to reflect upon one’s essence but a moneymaking opportunity. Parodying the existential novel in a contemporary post-capitalist context, St. Aubyn jibes that the death of an artist is often worth more, both fiscally and aesthetically, than their life, as if anticipating today’s Absolute Basquiat.

This becomes one of the more trenchant points of the novel: the author has become a commercial mechanism. Perhaps now more than ever, there is no longer any need for the author to reflect upon the existence or the nature of the world. In fact, any such rumination is foolish. The author must only produce: his or her writing is their product. Accordingly, the author need not have memory or awareness of the world, just ephemeral reactions that are linguistic commodities. Take, for example, the designs of artist and social activist Keith Haring, who tragically died of AIDS, which can now be seen on t-shirt and sneakers proliferating New York.

St. Aubyn makes an interesting deviation from the traditional existential novel in Charles’s use of drugs. “I have to own up and admit that I’ve experimented with the Prozac. I know I said I wouldn’t and I suppose that makes me an unreliable narrator.” Unlike our childhood favorite unreliable narrator in Charlotte Perkin’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” or Raoul Duke in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Charles’s unreliability is far less hallucinatory. He does, however, share qualities with both of these classics: he has a psychological disorder and is using drugs, but instead of symbolic visions, Charles’s prescription lampoons emotional disorders rather than innovating literary perspective.

An unavoidable point of comparison is Soren Aabya Kierkegaard’s Either/Or. It is one of the most intricate and Gordian of the classical existentialist novels. The novel juxtaposes two spheres of existence: the aesthetic and the ethical. The aesthetic being is obsessed with making life interesting — whether it be by means of erotocism or the art, hedonism is the underlying motivation and limitation of aesthete’s existence. Boredom becomes the root of evil. Kierkegaard poses the ethical being, who pursue moral question, as teleologically superior, insofar as he or she is unified in their stewardship of the good.

Putting Aubyn’s protagonist in conversation with Kierkegaard’s, Charles never elevates himself beyond the realm of eroticism. For Charles, even the existential novel which he writes is a product of his cultural hedonism. He consumes and produces trivialities without attenuation or regard for the greater powers around him. For example, Charles speed-reads twenty-six books on the nature of consciousness on the subway, but a few hours later can’t recall anything he has read. He is clever in the moment, but ultimately craven and inconsequential.

St. Aubyn’s novel ultimately becomes infected with much of the existentialist gloom that it mocks. The novel Charles writes, which occupies a sizable geography in A Clue to the Exit, is tedious and saturnine. The novel within the novel does little to illuminate Charles’s character or excavate the devices of fiction. Its primary benefit is to make Charles’s gambling and timidly masochistic sex seem more titillating by comparison. Ultimately, even with his raffish flares, Charles becomes a hackneyed trope.

St. Aubyn battering the existentialist novel produces a droll parody: morbidly ironic, A Clue to the Exit puts to rest to possibility of any novelistic consideration of existence as provincial and outdated. However, St. Aubyn’s novel becomes infected with the same tediousness of which it makes fun. It is purely reactionary, and offers nothing more than pastiche. Blighted by its own method, A Clue to the Exit has little to add to Tolstoy’s 1886 work besides a few witty barbs. While there are plenty of contemporary novels — too many to list here — that continue and expand the historic of social critique, St. Aubyn successfully inters the existentialist novel. I am reminded of Mary Jo Bang’s poem, “Except for Being, It Was Relatively Painless,” where she describes a world made of very pleasant dinners: anything more would be a dimwitted pretense.

This post may contain affiliate links.