On May 17th, the second half of Mad Men’s final season came to an end. Titled “The End of an Era” this set of seven concluding episodes follows upon the ennui and turmoil put in motion during the first half of the season, which aired last Spring. While the dramatic social transformations that have come to define the 1960s provide the backdrop to the characters’ circumambulations, perhaps Mad Men’s greatest aesthetic contribution is its citation of the banal and quotidian — rather than the catastrophic or epiphanic — as the grounds for its characters philosophic ruminations on the nature of the American experience during a moment of crisis and promise.

Nowhere is this tendency more clearly on display than the episode that marked the midway point between the first and second halves of the seventh season. The events of the Apollo 11 mission in July 1969 frame the episode, which revolves around protagonist Don Draper’s ad agency’s preparations to pitch an advertising campaign to a fast food chain called Burger Chef. Scenes of the characters watching various television sets with rapt attention punctuate the real drama of the show: Peggy Olson will give the pitch to Burger Chef since Don remains unsure of his future with the agency. In its broadest terms, Peggy’s leadership in this instance nods towards the burgeoning feminist energies of the 1960s. More locally, though, Don’s voluntary abdication of his position as the pre-eminent creative and emotional force at the agency indicates his growing acceptance of Peggy as an equal. Despite the relatively high stakes of this détente for Don, the episode continually reminds viewers of the limited horizons of Peggy’s personal victory. The team had planned for her to voice the position of “the moms,” and while she takes over the leadership role at the eleventh hour, she does so with the images of the United States’ first space cowboys flashing on the television in the background. To date, no woman has walked on the moon though twelve men have left their imprint on its terrain.

The role of the television set, perhaps unexpectedly, takes on a prominent position in the episode. Peggy begins her presentation by recalling Neil Armstrong’s historic first steps on the lunar surface, which occurred just the night before. Yet rather than celebrate NASA’s achievement or testify to her own awed response to the lunar landing, Peggy focuses instead on the televisual aspects of the mission. She claims that the nation’s thrall evinces a need for actual human contact in a world increasingly mediated by the screen. TV, in her reading of it, facilitates an experience of communal emotion and interrupts it. Burger Chef’s appeal, she notes, lies in the fact that their restaurants lack any televisions, thereby allowing family members to enjoy each other’s company without distractions. Rather than providing comfort or connection, the home, for Peggy, is instead a site of turmoil. Television, as Peggy describes it, disrupts the intimate space, forcing families to move into the public sphere to seek solace.

On the one hand, the scene serves as one of Mad Men’s many meta-textual moments where the television show comments upon its own status as a television show. On the other, Peggy is right to note the explicitly televisual nature of the space race and the ways that the intrusion of TV technology into the domestic sphere altered its parameters. In fact, despite the space race’s heady aims, these apparently banal matters proved such a source of contention and anxiety that engineers, astronauts, and government officials constantly and repeatedly returned to and rethought the question of manned space exploration. These scientists and bureaucrats were well aware that few would care about the feats of ingenuity the Apollo program represented if humans themselves were not featured at its core.

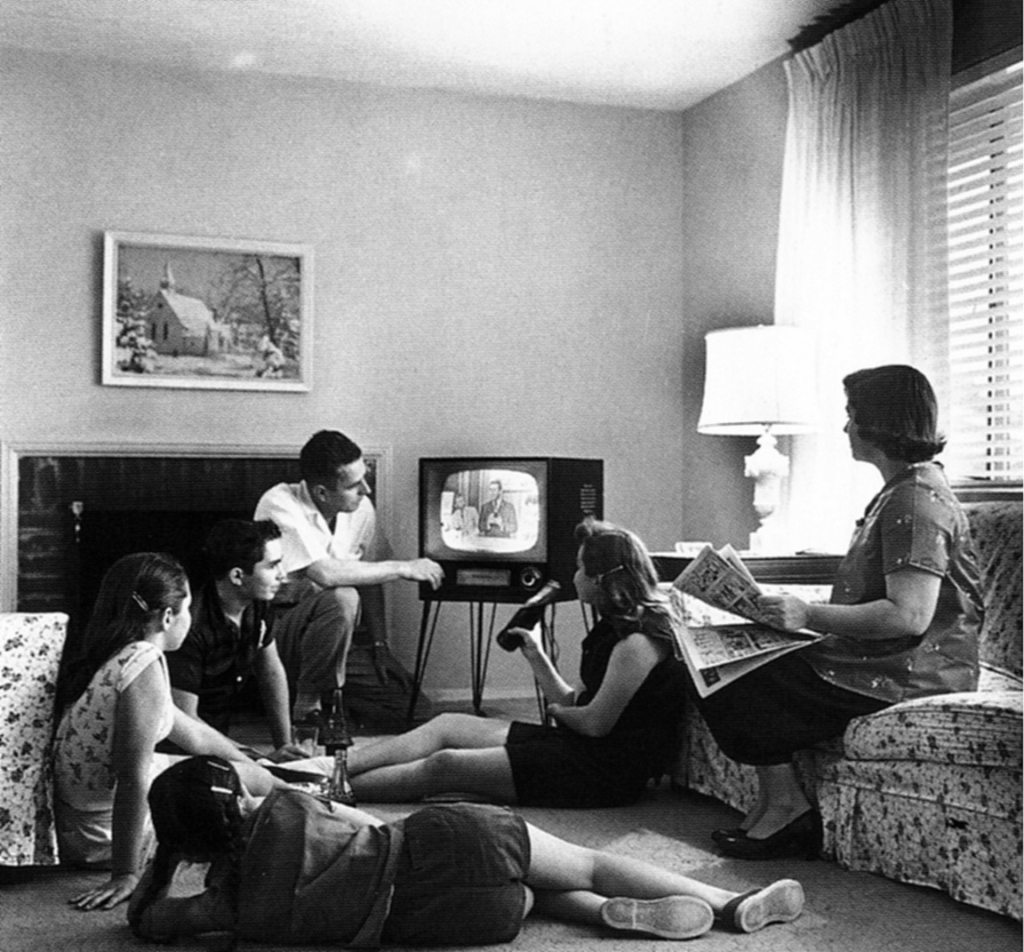

This tension is borne out in the ways that the footage of the Apollo 11 launch and landing were framed and in the response it solicited from audiences. If television provided viewers unparalleled access to the space race, then fluctuations in audiences’ viewing patterns always threatened to destabilize the sublime meanings NASA hoped to achieve. Largely due to the ubiquity of television, the 1960s saw a dramatic shift in the terms upon which the U.S. body politic participated in national affairs and in the image of nationhood the United States projected. Many audiences would have learned of the lunar landing, Stonewall riots, and later, the My Lai Massacre by watching the nightly news on their television sets. As J. Fred MacDonald notes in Who Shot the Sheriff?: The Rise and Fall of the Television Western, by 1960, 89.4% of U.S. homes had at least one TV, and by 1961 families watched an average of 5 hours and 22 minutes daily. In a supplement to radio technology, television viewers could see and hear events unfold in real time. This visual shift was also an experiential one. Audiences not only consumed interviews recounting recent events to them second-hand, they could also watch these events transpire before their very eyes. Even excessive violence was deemed an acceptable and necessary part of the integrity of television journalism: the Vietnam War was, after all, the first televised military conflict. Peggy alludes to just this ubiquity when she notes in her Burger Chef presentation that in the average U.S. home, the television set is located six feet or less from the dinner table.

This new media landscape reconfigured the options for interaction with national and international events as physical presence ceased being a barrier to participation. Unlike professional films — which until the advent of laser discs in the 1980s were mostly screened in cinemas or other public venues — sitcoms, news programs, and variety shows were developed with the home in mind. The presence of the television in the family living room thus transformed that space from a site of refuge or quiet — if it ever was one — to an information and entertainment center. If, as the scholar Benedict Anderson alleges, the newspaper unites a national body politic by joining them in a common endeavor, then watching television supplemented this sense of filial unity by furnishing it with moving images and sounds that could instantly transport viewers from their couches into the here and now experienced by their fellow country-members across the nation or globe. Audiences could “see” certain events transpire — rather than reading about them or hearing the broadcast on the radio — even if that “seeing” became necessarily hypertrophied. According to William D. Atwill in Fire and Power: The American Space Program as Postmodern Narrative, though thousands made the trek to Merritt Island to witness the Apollo 11 July 16th liftoff in person, over 500 million people around the world watched the live broadcast at home and in various viewing parties, repeating this ritual four days later as Armstrong descended from the lunar module and took his first steps on the moon’s surface. While the mission had a significant in-person component, the vast majority of viewers experienced the moon landing as a series of television broadcasts.

While television made the space race more broadly available than ever before, the domestic scene was also a potential barrier to its emotional salience. The footage of the liftoff on July 16th, 1969, was mediated even at the time by the ways that viewers were coached to watch their home televisions, and those programs in particular that dealt with the government and the military. Commercial endeavors, such as the many advertisements that instructed viewers on where to place televisions in their homes and how to arrange furniture around the new device, were supplemented by government bureaucrats’ own recognition of the enormous possibilities for national disciplining that television made available. Throughout the 1950s and 60s, the government aired dozens of public service announcements on the radio and television to prepare U.S. citizens for the prospect of a nuclear attack. These experiments with mass television broadcasting had a significant impact upon TV programming. In addition to the rampant militarization and surveillance the Cold War inaugurated, it also saw the birth of a federalized warning system, including sirens, tones, and standardized dictates for what to do in an emergency. The effectiveness of such systems depended upon citizens’ ability to distinguish certain sounds from others and internalize disaster precautions, a necessity that led to an aggressive education campaign on the part of the federal and state governments. These television and radio broadcasts coached citizens in what to do when under attack. Like Mad Men, the government cast these threats as catastrophic, but also quotidian: the price of doing business in the modern world. They demanded that citizens listen, learn, and then act upon the information presented in the public service announcements if they wished to remain safe.

Produced by various, often overlapping federal agencies, these TV segments, which aired on mainstream channels like CBS, NBC, and ABC, were part of a complex and detailed system of what Guy Oakes and Andrew Grossman call “emotion management”. These systems were designed to inculcate a palpable fear of nuclear attack in the U.S. populace, while convincing viewers of the real potential for survival if citizens abided by state suggestions for disaster preparations and procedures. These PSAs commonly maintain a lighthearted and family-friendly tone despite the dire nature of their message. Take, for instance, “Duck and Cover” a PSA from 1951 geared towards children that featured Bert, the Turtle. While Bert’s carefree stroll is interrupted by an explosion that annihilates the tree and monkey behind him, the soundtrack assures audiences that Bert “knew just what to do! He ducked and covered! Ducked! And covered!” The short film compares the risk of atomic war to other, more familiar disasters, like house fires or car accidents, catastrophes for which the state already had preparations in place. Though the announcer repeatedly raises his voice to convey the significant dangers the bomb poses, this narrative is paired visually with live action and cartoon recreations of nuclear attack and disaster preparations that make the threat of the atomic bomb seem continuous with the duties and pleasures of childhood, like school, play, and watching television.

But adults, too, were seen as in need of instruction and pacification. Those government broadcasts aimed at older generations fall into two main categories: simulations of nuclear attack that warn about the risks of ignoring disaster preparations, and controlled experiments that assure audiences of the potential chance, even if risibly slim, for survival. Like school drills where children cowered under their desks in anticipation of nuclear fallout, the irony and futility of these survival strategies were apparently not lost on Cold War producers, as evidenced by their frequently humorous tone and vague reassurances of success and safety. Indeed, after a cataclysmic opening, the shows follow a number of plotlines, such as tests of canned goods in simulated nuclear attacks, cartoon recreations of life after ballistic apocalypse, or housewife-journalists’ chipper descriptions of the obliteration of all that stood in the practice-blast’s path. The ideal viewer was thereby trained by these broadcasts to see explosions as awesome, yet routine; survivable through the careful, repeated, and systematic planning of which they were an integral part. There was a symmetry between these bomb safety videos and the July 16th Apollo launch. By the time of the Apollo 11 liftoff, viewers already knew how to watch television as a group, where to sit, what to say, and what to expect. Moreover, they expected the home to be a primary location for this kind of heady nationalist watching. Disaster and triumph became another set of eventualities, ones that television could help viewers practice, prepare for, and witness, at least through their screens. But these events depended upon television as much as it depended upon them: TV both created its audiences and informed them.

Such expectations have much to do with TV’s predictability, a predictability that was a standard part of PSAs about atomic attack. Despite the different aims of the various broadcasts, they almost all begin in the same way. The opening sequence displays the show’s title — which sometimes appears only gradually against a darkened screen, as though being assembled from the debris of nuclear fallout — while music plays in the background. These soundtracks are alternatively jaunty, similar to the themes from shows like Bewitched or I Love Lucy, or feature string instruments playing in an eerie minor key, related in effect, if not in kind, to the opening for the Twilight Zone and other shows about paranormal activity. The programs’ inaugural sequences are soon interrupted by the sound of an explosion as the screen goes entirely white. This practice occurs in almost every single one of the dozens of PSAs I’ve viewed. More so than any other element, then, the inclusion of this white-out screen followed by an image of a mushroom cloud defines the genre.

In this instance, the similarities between Cold War PSAs and the space race are about more than an implicit process of disciplining. The televised broadcast of the Apollo 11 launch duplicates many of the visual conventions of such programs, the white-out screen in particular. In Walter Cronkite’s famous coverage of the liftoff, as the ignition sequence begins, the camera cuts from a high-angle shot of the rocket to a view of the rocket’s underside. The perspectival shift allows television audiences to marvel at the force of ignition. As the rocket blasts off and debris from the bonds that formerly secured the shuttle to the earth fall towards the ground, the rocket’s flames consume the visual field, briefly turning the screen white. The letters “USA” flash past the camera as the rocket careens into space and astonished spectators, both at home and on the base, look on in awe. In mimicking the well-known iconography of ballistic explosions, the footage of the July 16th Apollo 11 launch refers to these very disaster preparation videos. Given TV viewership at the time, the iconography of nuclear attack would have been easily recognizable. Moreover, the fact that private and public footage of the liftoff make use of the convention of the screen white-out — CBS and NASA both displayed a whited-out screen in their July 16th footage — testifies to the ways producers and government agents represented the mission as deeply entrenched in Cold War nuclear culture. The parallels extend to the different broadcasts’ soundtracks as well. The sound of the rocket blast off is almost identical to that of bomb blasts in the government PSAs. While this alone may be unsurprising — the Mercury rocket was a military rocket after all — these parallels further solidify the resonance between the footage of the Apollo 11 liftoff and Cold War programs warning about the threat of nuclear attack.

By 1969 television served a purpose beyond “mere” entertainment. It was also a source of instruction and planning, evidence of technological advance, and a way to document feats that stretched the limits of human ingenuity. Yet these features — the ability to forestall disaster and destruction — were inevitably bound up in the production of the specter of disaster in the guise of nuclear war. When Peggy suggests that the family watching TV while they eat dinner engages in an exercise that alienates as much as it unifies, she gestures towards the very themes that populated both fictional and journalistic television programs at the time: war, paranoia, infiltration, and violence. To watch Neil Armstrong take his first steps on the lunar surface on July 20th, 1969 was to recognize that the very technologies that delivered him to the moon might also bring about, in the words of William Faulkner “the end of man.” Many citizens might have expected that they would have learned about such ends by watching their televisions, the very devices that had allowed them to bear witness to what Richard Nixon, a relative skeptic of the space race, called “the greatest week in the history of the world since Creation.”

The titles that Mad Men’s producers gave to the first and second halves of the seventh season (“The Beginning” and “The End of an Era”) seem particularly fitting. So, too, does their use of the Apollo 11 mission as the transition between beginnings and endings with Peggy referring to the dinner table as a battleground. If the television inaugurated a new media age, then it gave the lie to the home as the site and protector of American innocence, if anyone ever really believed that such innocence existed in the first place.

This post may contain affiliate links.