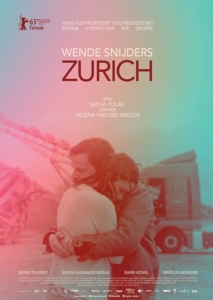

With her sophomore feature, Zurich, which premiered at this year’s Berlinale, Dutch filmmaker Sacha Polak nurtures an auteurist bent. In its fierce portrayal of sexuality, and almost obsessive filmic portraiture of a tormented female protagonist, Zurich is strongly reminiscent of Polak’s debut film, Hemel (2012). After Hemel was honoured with the FIPRESCI award at the 2012 Berlinale, Polak reprised her collaboration with writer Helena van der Muelin for Zurich. The script of the film was picked up for the four-month Berlinale residency in 2013. Even though the two films share obvious qualities, stylistically and thematically, Muelin clarified at the festival that Zurich was not a follow-up to Hemel. Regardless, Zurich asserts Polak’s predilection for knotty narratives of grief and elusive love.

With her sophomore feature, Zurich, which premiered at this year’s Berlinale, Dutch filmmaker Sacha Polak nurtures an auteurist bent. In its fierce portrayal of sexuality, and almost obsessive filmic portraiture of a tormented female protagonist, Zurich is strongly reminiscent of Polak’s debut film, Hemel (2012). After Hemel was honoured with the FIPRESCI award at the 2012 Berlinale, Polak reprised her collaboration with writer Helena van der Muelin for Zurich. The script of the film was picked up for the four-month Berlinale residency in 2013. Even though the two films share obvious qualities, stylistically and thematically, Muelin clarified at the festival that Zurich was not a follow-up to Hemel. Regardless, Zurich asserts Polak’s predilection for knotty narratives of grief and elusive love.

The director’s next, more ambitious project, a film adaptation of Eileen Atkins’s play Vita and Virginia — a dramatic interpretation of the romance between Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West through their epistolary exchange — might be served well by her work so far.

Zurich regards the indignity of a woman’s bereavement when her greatest loss is also her darkest secret. In her acting debut, Dutch singer Wende Snijders plays the protagonist, Nina. As Nina grieves the death of her lover, Boris, her process of mourning is implosive, tested by the revelation of his betrayal — a marriage and family unbeknownst to her. Most disturbing of all, however, is the depiction of Nina’s self-inflicted degradation.

The film is narrated in two chapters, “Hund” (“Dog”) and “Boris,” that are chronologically reversed but in “emotional order.” The first chapter nosedives into Nina’s unravelling and studies her unmoored disposition, posing questions about her backstory, with only suggestive glimpses — of Boris as an apparition, and a missing daughter — into her past.

In Kelly Reichardt-ian fashion, the caustic meld — coalescing anger and contrition — of grief is accentuated in the placidity of vistas and wide roads. The visual document supersedes dialogue (written in Dutch, German, and English), which is sparse. Boris, a truck driver, died in a road accident, and Nina’s acute sense of displacement finds illusory redemption on Boris’s route. In her attempt to retrace his path, Nina drives and hitches rides through the film — which has been described as a “musical road movie.” Although labelled a musical, Zurich doesn’t make this aspect very obvious. The film samples a couple of country and pop songs — played at a festival and roadside bar Nina visits — and the score alternates between lachrymose string sections and choir hymns. The few times Nina is mildly jolted out of her stupor is when she listens to music. A former professional choir singer, she reflexively starts to sing along, but it’s always an awkward act. In one such scene, as she joins a live band covering “These Boots Are Made for Walking,” even in the few moments that she barely forgets, she is still tethered to the tension.

Zurich was written keeping Snijders in mind, and Polak does a great job of mining the pop singer’s intense stage persona for the dark, conflicted character. For a first-time actor, Snijders delivers an impressive performance — effectively conveying the volatility and complexity of emotions, coupled with a bestial physicality. Her countenance moves effortlessly from a flicker of remembered joy to severe impassivity. Nina’s vulnerability, child-like naïveté, and stone-cold savagery, are all beautifully manifested by Snijders.

Casting her relationship’s legitimacy in a dire, unforgiving light, Nina’s search for belonging is a tempestuous one. In the first chapter she steals a dog — which is later revealed as being Paco’s (Aäron Roggeman), Boris’s son from his marriage to the other woman — and in her hapless search for intimacy, she encounters another truck driver, Matthias (Sacha Alexander Gersak), whose compassion offers transient refuge. Her insistence on obscuring her past eventually pushes Matthias away. The chapter closes with the dog being run over on the road, in some way rehashing the tragedy.

The film’s unique engagement with grief is occasionally broken by Polak’s use of cinematic tropes, like a recurring, morbid dreamscape showing Nina — the weightless billowing of a flowy chiffon dress trailing her — diving into the sea to rescue Boris. In another similar scene Nina is shown making love to a faceless monstrosity, his sentient features mummified in speckled skin, evocative of a stifling memory.

In the second chapter the pieces fall in place, with a cursory observance of the fast-disintegrating remnants of Nina’s life heretofore — her daughter, Pien, her role in the choir, the semblance of a woman well put together. Nina is rather distant towards Pien in the immediate aftermath of Boris’s death. Her disregard for the child compounds her angst, and in the final act of the film, she drops Pien off in the fenced porch of Boris’s other family while they are away at his funeral. Polak has referred to Nina’s character as a “childless mother” and sought to challenge the social stigma and greater moral burden borne by a woman abandoning her child over a man doing the same.

Polak glazes over the mourning of the others, who experience the same physical loss as Nina, but their grief is familiar, monotonic, the kind that will be reconciled with the passing of time. The wife crying inconsolably is shown in a quick frame. Paco is seen angry, defiant, walking away from his father’s grave, he eventually gives in to his teenaged friends bantering about if Boris willed his own death, allowing for the prescribed measure of levity to deal with the hurt. But Nina realises and charts the emotional abyss in a physical landscape, making it her reality. In all of this her process of grieving is difficult, nebulous, humiliating, and dehumanising.

Although Vita and Virginia will reportedly stray from the darker portrayals of Woolf we are accustomed to seeing, and channel the author’s wittier side, Polak’s engagement with complex female characters should lend to an intelligent and layered adaptation of the storied love affair.

Neha is a freelance writer, and was formerly an assistant editor at the Indian edition of Rolling Stone Magazine. She holds a Masters in Cultural Reporting and Criticism from New York University. Her work has appeared in Kirkus Reviews, Los Angeles Review of Books, Rolling Stone India, the New York Observer, Virgin Music, Vulture, and the Daily Beast.

This post may contain affiliate links.