Despite the increasing reciprocity of global culture and its transformative effect on American identity, the pursuit of the Great American Novel has continued unabated since its 19th century heyday. If it is something of a literary grail, it also comprises a latent dream of American creative enterprise: surmounting time, class, and race in order to capture the national Zeitgeist, while bridging the imagined American promise with the more sordid American reality in the process. It springs from a generous impulse, a kind of national yearning forged from the unique alchemy of a democratic mythos, vast landscapes, and fealty to a vision of populist potential. Yet the Great American Novel has proven maddeningly elusive to even our greatest writers — and with good reason. After all, where does the heart of American narrative beat loudest and truest? The arcadian promise of Hawthorne’s wilderness? The picaresque urbanity of Bellow’s Chicago? The weight and horror of Melville’s seas?

As we comb through the divergent strata of American experience and realize the impossibility of its summation — while also taking sober inventory of the cultural framework of late capitalism — it seems fair to ask a vertiginous question: what if the Great American Novel isn’t a novel at all? What if the garbled images, advertisements, slogans, celebrities, and spectacles of the American cultural experience are its most lasting testament? If this is so, the novel’s very intelligibility might disqualify it as the ideal mode for a pancultural statement. Perhaps we should look, rather, to the glut of popular surfaces and sounds: the disconnected (but not incoherent) realm of Pop Art. Put another way: in depicting the primacy of mass culture, the ascension of brand and the technological reproducibility of the image — that is, the crass materialist backdrop of American life — was it in fact Warhol who wrote the Great American Novel?

Dustin Illingworth writes a monthly column for Full Stop on the intersections of technology and literary culture. Based in southern California, he is currently at work on a debut novel and a collection of literary and cultural criticism.

From Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin to Dos Passos’ USA Trilogy, from Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby to DeLillo’s Underworld, the enigmas of our national character have been continuously shaped, combined, destroyed, and resurrected within the cauldron of a self-consciously national literature. From our first faltering steps toward a new American consciousness (so apparent in Whitman’s egalitarian sprawl and Emerson’s transcendental mysticism), literature has played a profound role in the establishment of a particularly American identity — in a sense, America didn’t exist until it was written. And though this construction of a social imaginary has historically underrepresented women and peoples of color, it nevertheless continues to serve as a powerful wellspring of personal and collective myth. We write to know who were, who we are, who we will be, and there remains an almost magical belief in the ability of the Great American Novel to tease out a satisfactory answer to the permanent question of American life.

But within the 20th century’s farrago of teeming mass culture and industrial capitalism, the purview of the American novel seemed to shift away from an idealized democratic vision, becoming instead a way of cataloguing the schizophrenic niches of modern consciousness. It would be difficult to argue that the work of Barthelme, Gaddis, Barth, or Coover was shooting for anything approaching a moral consummation of American character. Rather, in its metafictional gamesmanship and ironic detachment, the novel became a kind of study of the variety of American cultural neuroses. And with the advent of mass entertainment — television, film, and the cheap glitz of the celebrity cult — the reading of serious novels became the practice of a sophisticated minority rather than a communal form of infinite potential. By virtue of their very ubiquity, modernity’s cacophonous symbols and sounds displaced the novel’s textual authority, at least in the lives of the uncultured masses (whom the Great American Novel once strove to embody and ennoble). With everyday life increasingly drenched in the aesthetic experience of advertisements, disembodied voices, music, and moving images, it seems fair to conclude that the real revolution of 20th century art occurred not by way of avant-garde literature but rather within what the late, great Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm called the combined logic of technology and the mass market — that is, “the democratisation of aesthetic consumption”.

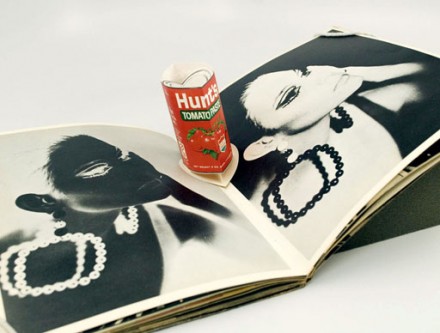

Enter Andy Warhol. Working under the presumption that media saturation had become our most recognizable shared experience, Warhol played with Walter Benjamin’s conception of artistic authenticity in the age of technological reproduction, intuiting that everything seeks its highest reality in print or on film — what DeLillo has called “floating an image free of history.” The iconography of Warhol’s Pop Art — Mao, Marilyn, Elvis, the endless cans of Campbell’s soup — is immediately grasped by anyone living through consumer society as a new kind of image-alphabet. Rather than a single representative work, it is Warhol’s oeuvre taken together that becomes a kind of surrogate text, a surrogate novel. If the aim of the Great American Novel is to seize on a particular feeling, a sensation of life that condenses the American experience, Warhol’s images — somewhere between art and acknowledgement — capture a reality extant from Chicago project to Orange County bubble, from rural farmland to urban neighborhood, from migrant family to upwardly mobile technocrat. Using the visual language of an entrenched, sprawling popular culture, Warhol peered beneath the American subconscious and found it garish, narcissistic, hyper-imaged, technologized, and repetitive. In a sense, he sold us to ourselves.

With globalization reaching its fullest realization, mass culture has become broader if not deeper. We live in a time of selfie sticks, virality, surveillance (and its attendant imagery), data as commodity, terrorism, ad exhaustion, device envy, memes, freemium apps, productivity solutions, and “content” rather than text. Warhol’s intuition proved prophetic. His novel grows with every Coke can, cronut, and Kardashian cover, a ponderous and self-replicating tome. Still, it isn’t so much that the traditional novel is dead or dying — hell, I’m writing one (and you probably are, too); rather, it’s the concept of the Great American Novel that, I feel, requires refinement, maybe even dismissal. The moral crises of the global village, the effect of technology on inwardness, the social cost of our app-mediated relationships — these (and countless other issues) are neither uniquely American nor exclusively earmarked for novelistic treatment. The novel, as always, must fight for purchase and relevance in the clamor of our techno-cultural babel; as such, perhaps we need fewer Great American Novels and more great novels — that is, books more concerned with glorious, horrifying contemporaneity than outmoded, self-conscious myth baiting.

To wax Warholian, the Great American Novel’s fifteen minutes may be up.

This post may contain affiliate links.