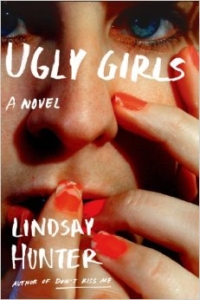

Ugly Girls is the story two girls in late high school. Perry and Baby Girl spend their nights somewhere near a highway in America, jumping out of trailer park bedroom windows, stealing cars, talking back to gas station servers, and daring each other to ever more brazen feats of not giving a fuck. The narrative follows the girls, and those close to them, over the course of the days leading up to their eventual meeting with an internet predator “Jamey” who, before we meet them, has been contacting both via Facebook. His misspelt messages punctuate the story; he is characterised (and flagged as a risk, an older person faking being a kid) by his use of “corny-ass text speak that no one she knew used except for him”.

Perry and Baby Girl are introduced in an opening sequence spanning one night’s rampages and two chapters, in which they stake their claim to the ugliness referred to by the title. The first chapter is in Baby Girl’s voice, the second in Perry’s, and each of them offers the reader functional yet complex introductions to the other. Baby Girl, we learn from Perry, has a half shaved head and dresses like a boy since her badass small time gangster brother Charles suffered a brain injury after a motorcycle accident that left him changed: soft, childlike, and vulnerable. She’s sacrificed her prettinesses, ditched her femininity to channel his former self, keeping the old Charles alive by going out ‘thugging’ with Perry, though alone with her brother she’s soft and tender, even caring. Perry is less clearly harbouring secret fucks to give, and whether she does what they do out of support for Baby Girl or for her own satisfaction is not obvious to the reader. Her favourite comeback is ‘oh well’, she wants them to steal an SUV so she can sit ‘up high’ and, in contrast to her friend, she is described as pretty, perhaps beautiful. Baby Girl on the other hand “wanted her outside to look like how she felt on the inside. Which was Fuck you.” This contrast and Baby Girl’s self-analysis — she “wasn’t as pretty as Perry but she was meaner” — establishes a certain beauty and the beast vibe.

FSG, the book’s publisher, describes their dynamic interplay of ugliness as something of a dialectic, “Ugliness is something they trade between themselves, one ugly on the outside and one on the inside.” The girls certainly share the strategy of ugliness, the way kids might trade tricks on how to illegally download movies, but to me it seemed that what is portrayed here is more complex than a comparison of inner versus outer ugliness. To define the inside and outside of close friendships between teenagers seems to me to be a fool’s errand and a trap Lindsay Hunter is too smart to fall into. It might be more accurate to say it is not quite clear where Perry ends and Baby Girl begins. Their friendship is also a partnership in crime, in that their co-dependence is both business-like and criminal. On the first page Hunter writes: “Sometimes it seemed mean thoughts were all she [Perry] had for Baby Girl, but when she caught sight of herself in the side mirror she saw she was doing all the same shit.” What the girls have abandoned in their rejection of prettiness is made clear when they argue with a gas station cashier. Riled by Baby Girl’s taunts he says to Perry, “You are a pretty girl. You should be at home asleep in your bed with curlers in your hair” and then when they walk away from him he yells “Ain’t nothing open past one a.m. but legs!”

The first time I read Ugly Girls I read it at speed, under twenty-four hours from cover to cover. Pre-internet speed — like I used to read as a twelve-year-old. Twelve-year-old me would have downed Ugly Girls like a glass of freshly squeezed orange juice. I would have read it on the coach to school, in the corridors at school, blocked out taunts with Lindsay Hunter’s words while waiting for a lesson to start. In 1995 twelve-year-old me had never heard of the internet. To twelve-year-old me Ugly Girls would have been Science Fiction. Twelve-year-old me wouldn’t have known that in just a year’s time, I too would be able to chat with strangers online.

I am less comfortable with the book than twelve-year-old me was. I am keenly aware of the problems with trying to protect anyone other than myself from “the wrong kind” of representation. I read Ugly Girls with my heart in my mouth, just waiting as I read for it to fuck up, for the moral of the story to materialise, for the lines to be drawn and for its subjects to be judged. I don’t trust adults to write about youth as much as I did before I became an adult myself. I’m rooting for Lindsay Hunter. I desperately want a book about poor working class girls who choose ugliness as a means to seize the will to power to work.

I like the idea of something that’s less comfortable for an older person to read than it is for a younger person.

The principal adult characters in Ugly Girls — Perry’s pain- and beer-ridden mother Myra, Myra’s partner Jim who works nights in a prison, and Pete, their enigmatic baby-faced trailer park neighbour — are not comfortable people. Hunter renders them, their pain, their fatigue, and their hard-earned wisdom with tenderness, understanding, and almost total moral restraint. Jim and Myra, though they struggle, are given, in the chapters written from their point of view, great emotional insights, and their love for each other, and Perry, is clear. Both know she goes out at night but neither say anything, Myra because she inherently trusts her daughter and “Well, she had decided long ago she wouldn’t be two-faced with her own daughter like her Momma had been,” Jim because he, when Perry tells him she was asleep in bed, wants her to think he believes her, wants her to trust him, and is too tired from work to do anything about it anyway. Pete’s slightly menacing friendliness — he thinks Myra should worry about where Perry is, “What if she’s out doing wrong? Or tied up in some maniac’s closet” — is given heart-curdling sweetness by Myra’s observation of his cleft palate, “His Momma hadn’t cared for that scar right. It bubbled up like a grub worm.” It is Myra’s interior monologue, her nostalgic reminiscences of her own youth and her thoughts on her relationship with Perry, which offers the clearest way into the deeper resonances of this story, the tenderness that is, despite the ugliness, never far away in this text. The characters’ relationship to each other in time, their ages, their relative innocence or experience, what they have learned, these are the great strengths of this work.

I’ve been trying to figure out why Hunter chose The Internet Predator as the dramatic trope around which Ugly Girls’ narrative is structured. It’s the aspect of the novel that I am least comfortable with and I associate this kind of subject matter more with advertisements for parental control apps and the conservative UK government’s arguments for internet censorship. I don’t agree with those that believe it’s the job of literature or art to provide role models or moral guidance for young people. I suspect those younger than me might know better how to deal with such problems than I, after all, they’ve been working that harder faster broadband connection from a much younger age. Hunter’s intention to subvert weakly reasoned assumptions about the safety of young people online is clear, but I still wonder if the baggage on this particular cliché is worth it. Hunter has written that the book is about “The Internet as predator” which sounds great, but again I wonder if internet predators — adult men who pursue sexual relationships with minors via online channels — are, post NSA revelations, even the most predatory thing about the internet. I’m coming to the conclusion that it’s meant to be like a Reefer Madness kind of thing, the issues-hung narratives of young adult literature dealt with the blasé nonchalance of cult fiction. We’re somewhere on a continuum here between Judy Blume and JT Leroy, and I can’t help but feel that the kitsch of the plot clashes somewhat with the beautiful neon realism of Hunter’s characterisation and prose in a way that works against it. When the big climax of the story hits I’d anticipated violence, ugliness, possibly horror, maybe even triumph, but what transpires is, though dramatic, in contrast to the defiant opening of the story, overwhelmingly bleak. Lost somewhere in the drama is the subtlety of feeling found earlier on in the novel. There is a sense of disappointment and a settling with horrid inevitability into the defeat and violence and sadness of the everyday.

The girls’ friendship falters into antagonism; they do not save each other. They can handle the bad man from the internet but they can’t handle each other or the way adults respond to the power they’ve seized. Hope is crushed by the consequences facing them as a result of taking their lives in to their own hands. Their revolt is nipped in its ugly bud without a chance to be recognised as enduring in possibility. There is less victory in this coming-of-age drama than in any I’ve read before. Perhaps this is a bold move by Hunter, an honesty, but I am left, as many have been, shocked by its cynicism. “It” does not get better though, and Hunter is probably right to avoid saying so. When the moral comes in Ugly Girls, it is not on the heads of the young protagonists that it falls but on those of the most desperate and miserable adults around them, though the consequences are borne (as perhaps they must always be, while adults continue to believe in protecting innocence) disproportionately by the younger characters. I hope that for those younger than I to read the very bleak honesty of this revelation might in itself be enough of a shock, a jolt to the mind, to be liberating. I, in my weariness feel denied the satisfaction that would have been provided by fantasies of triumph, I feel my age. The beauty of an image on the first page of the book, “The rising sun the colour of a pineapple candy, no more than a fingernail on the horizon” haunts me. I had hoped, I guess for a happy ending, but ultimately I hope that the fate of this book, unlike the fate of most things, will depend on the way that it is read by people younger than myself.

Hestia Peppe is an artist, writer and sometime governess; a line tamer, a fire starter and a keeper of connections. She lives in London.

This post may contain affiliate links.