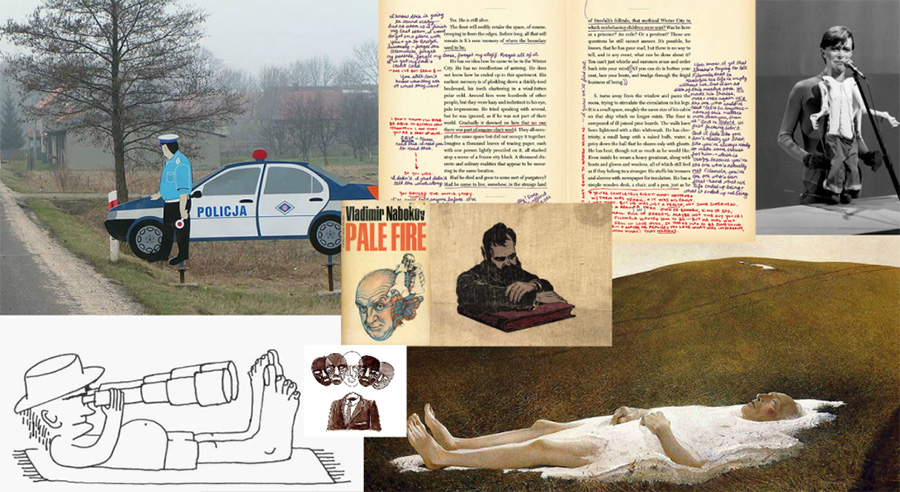

2014 has been a fruitful year for the features section of Full Stop. We’ve had the pleasure of editing and publishing some incredible essays, and have collected ten of our favorites below. This year our features writers have tackled topics ranging from police ontology to Bowie fandom, and from the Midwest in the literary imaginary to the pitiful lack of diversity in contemporary publishing. Feature essays are often personal, like Andrew Mitchell Davenport’s reflection on mixed-race identity in America, and Rebecca Sacks’ exploration of her late grandfather’s marginalia in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. Full Stop features are also incisively critical, like Jesse Miller’s essay on language, virality, and an ethics of care, and David Burr Gerrard’s critique of Geoff Dyer and the hunger for purpose. Some of the best pieces are both, like Aaron Braun’s dispatch from his job at an artisanal popcorn store which develops into a critique of boutique employment practices, and Rachel Luban’s assessment of three postmodern novels which begins anecdotally with a fleeting relationship built on literary exchange.

The features section of Full Stop is where we publish our longest, most in-depth and most labor-intensive pieces. We pay our writers for these pieces, well above the industry standard. We do this because we believe in cultivating literary and critical voices — our mission as an organization is to engage in and foster an earnest, rigorous, and expansive literary conversation. But we’re also a non-profit and we operate on a shoestring budget, so in order to continue this important work we ask you to donate a few bucks. If this list of features from the past year moves or excites you, please consider making a contribution. We look forward to bringing you another great year of features at Full Stop.

Reading with Louis by Rebecca Sacks

My grandfather wrote almost without exception in a soft pencil. His handwriting is to me like a human voice. I recognize it in all its varieties: here he was rushed, here adamant, here his hand shook . . . I could provide a sample page, but I will not. I am too jealous, too insecure. If another reader were to see Louis’s page and understand a reference I had failed to grasp, or sense better than I the point he wished to emphasize in his underlining, that reader would have found my grandfather. This is our last vestige of intimacy. I would not allow you to read his book any more than I would let you smell a sweater that still had his scent, if such a sweater still existed.

Notes on Not Passing by Andrew Mitchell Davenport

Today a housing project stands in memoriam to Johnson. As I walked by the building, a woman yelled “Cracker!” at me as she passed. My girlfriend laughed, saying that old black witch was too stupid to know any different. The woman seemed sane, unlike the aging militant who yelled after me last year to get out of Harlem. My identity had taken a socking, but perhaps my assailant hadn’t heard of John Ruskin. He said colors aren’t fixed. They pass into one another. Identity runs like colors subtly multiple on skin. I’m El Salvadoran to an Oaxacan, mulatto to a Haitian squinting her eyes, black to the negro curious about America’s slave past, and white to any Anglo too busy finding what they want to see there. But I have staked my claim as a man with both European and black blood in me. I will not be one who hides, nor should I ever have to. I’m one of Murray’s Omni-Americans, one of Walcott’s red niggers. Either I am nobody, or I am a nation.

Police Unreality by Sam Kriss

The most obvious fact about the police is also the most unsettling, which might be why it’s rarely mentioned: cops aren’t real. This isn’t to say that they’re some kind of figment of the collective imagination; they’re plainly here, but theirs is a presence that doesn’t seem to have the same kind of existential rootedness as more usual objects: tables and chairs and criminals and so on. Cops seem to hover just on the wrong side of any sensible ontology; for all the direct physicality of their violence, there’s also a lingering sense of the unearthly and the spectral. This might be why people tend to get so spooked by them: approval ratings for the police tend to fall after any kind of encounter. It doesn’t matter if they’re baton-charging your picket line or returning your lost cat: there’s something about cops that produces a kind of queasy, crawling revulsion. The sense of a ghost at the feast. It comes out in the names we find for them: scum, filth, pigs. Cops induce abjection; they’re neither subject nor object but disturbingly liminal.

Dyer’s Straits by David Burr Gerrard

Writers are workers, or at least we can be. We can examine official language and expose its evasions; one thing that is so disappointing about Geoff Dyer’s Another Great Day At Sea is that, writing about an endless war that continues to produce appalling abuses of language, the only instance that Dyer can muster the energy to complain about is a trivial misusage of the word “engulfed.” Perhaps more importantly than our duty to language, but inextricable from it, is our duty to tell stories, not only our own stories but those of other people. But in order to tell anyone else’s story — or to tell our own in a way that will have relevance to others — we must have belief in our ability to do so. To avoid solipsism, we must have self-respect.

Change in the Land: Willa Cather’s Midwest by William Harris

Even to someone like me, who has spent nearly his whole life in the Midwest, Willa Cather’s writing can seem exotic and uncanny, a revealing impression about the Midwest and its transformations. Familiar place names billow out lush, foreign-sounding natural taxonomies, mixed with things I’ve long experienced, like the “stimulating extremes of climate.” This is a personal and contemporary reading, but it’s also one that tempts me to go further. Perhaps the profusions of nature in Cather hint at her escape from the prairie and move to New York, her mind muddled and excited by the slips and inventions that disturb and delight those who reflect on home after leaving. You can imagine this subdued kind of exile to have about it a sense of enormity or its opposite, but either way it led to a looking back. Did the prairie become exaggerated along the way? Did it attain a higher brilliance of color?

Going Viral by Jesse Miller

Alena Graedon’s The Word Exchange and Ben Marcus’ The Flame Alphabet treat language as a virus not merely to acknowledge that language is as much in control of us as we are in control of it, or that ideas spread through networks of communication at exponential rates, but to suggest that there is something lacking in the way people engage with language. Call it empathy, call it care, call it love — the problem of its absence requires an imagined epidemic to articulate the path to cure. These books challenge the commonplace distinction between the seductive ignorance-as-bliss and the democratic knowledge-as-power. Through figuring and taking seriously the potentially traumatic capacities of language, these novels confront a set of ethical dilemmas regarding who speaks, how, and at what cost.

The Meaning in the Margins by Rachel Luban

What’s the purpose of the authorial mystery story, not the whodunit but the whoisit? Books of this form necessarily suggest questions about reader involvement, the importance of the author, and the limits of fiction: why do we care which fictional character “really” wrote something when we know that the name of the true author is always printed on the front cover? How many layers deep does suspension of disbelief penetrate? Why should, and how does, the attribution of a work of art change our experience of it? The commentary format further emphasizes the act of reading. Interpretation, usually something that unfolds outside the book, is itself the subject of the book. In all three novels — Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, and S. by J.J. Abrams — we watch as our readers-cum-writers are taken over by what they read. These books are formally designed to address reading — but to what end?

David, What Shall I Do? by Lauren Friedlander

Even into college, I preferred to be quiet and chameleonic, “I can’t get a read on her” registering as a compliment of the highest caliber. I wanted to be unknown, but questioned — assumed agonizingly mysterious for my muteness, rather than dumb. Such was the height of my vanity. My Bowie fandom made me voyeur to a life grittier than mine, dirtier and harder and sweatier. Simon Critchley says, “There is a world of people for whom Bowie was the being who permitted a powerful emotional connection and fed them to become some other kind of self, something freer, more queer, more honest, more open, and more exciting.” My college boyfriend said I walked like I thought I was a glam rock wolf in an Old Navy fleece. In an effort to show him who I was, or at least who I thought I was, I made him listen to the whole of Station to Station by way of explanation, lying in utter silence on the twin bed in my freshman dorm room, childhood Beatrix Potter quilt underneath. (When the same boy discovered cocaine, he tried to convince me of all the good it had done for Bowie in the late ‘70s, when the man subsisted entirely on a diet of milk, coke, and peppers, confident that witches were trying to steal his semen. Surely I would understand!)

Dispatches from the Labor Market by Aaron Braun

Confused college grads, therefore, may be living by a different but related dictum: “do whatever,” an awkward purgatory between doing what you love and surviving. Like its more positive counterpart “do what you love,” this avoidance of “bad work” is concerned with ideals of personal autonomy and individuality. For freelance workers, serial interns, and frantically scheduled busboys and baristas, a state of precarity may seem like a best option, or even a selling point and a source of pride, when the options available for steady work appear increasingly daunting. Employers play on this desire, promising an ad-hoc schedule and a playful work environment.

Hatred of Publishing: A Conversation Between Industry Dropouts by Jennifer Pan & Sarah McCarry

In my politics, I’m not really a “let’s pack up and move to a hippie commune if we don’t like society” type, but I do think that spirit transfers pretty well to a lot of cultural production. Tons of people who quit traditional publishing (or never even got their foot in the door) go on to start incredible independent publications, or found small presses, or write books, or any combination of the aforementioned. And it goes without saying that a lot of those people have radical inclinations! But the question then becomes how to make these DIY projects sustainable, in the absence of the kind of capital that traditional publishing commands. There’s obviously a lot of volunteer labor that goes into these side projects, and people have rightly pointed out that the idea of “labors of love” often becomes a justification for exploitation. Dropping out of publishing is definitely not a perfect solution, but I don’t know of a better one at the moment.

This post may contain affiliate links.