“You don’t tell a story only to yourself. There’s always someone else.

Even when there is no one.”“By telling you anything at all I’m at least believing in you, I believe you’re there, I believe you into being. . . . I tell, therefore you are.”

—Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

When I’m feeling melodramatic about my fear of eco-apocalypse, I insert phrases such as “If the world still exists then” into casual conversations regarding our impending future. While I understand that climate change poses many real and serious threats to our near future — to say nothing of the related problems we’ve already faced — my realistic side asserts that the question should be more along the lines of what the world will look like then. Which is all to say that I was quite struck when I first read the news of Katie Paterson’s Future Library Project.

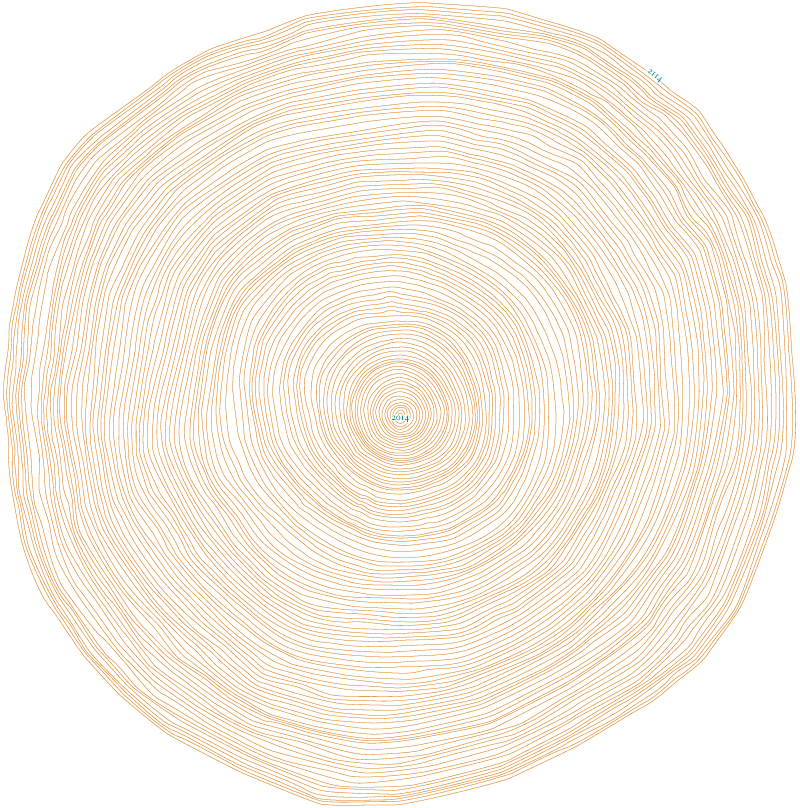

The Future Library Project will, for the next hundred years, choose an author each year to contribute a work to the library, which will publish a final anthology for the first time in 2114. This is a clever piece of concept art. To me, however, the most thought-provoking element of Paterson’s plan is the way in which she initiated the project, by planting a forest of trees in Norway in 2014. Over the next hundred years, they will record in their growth rings a record of climatic changes in the fragile North, and ultimately they will die to give birth to the printed anthology. Margaret Atwood has already agreed to be the first contributor to the project, offering an unpublished novel of hers to remain unread for a hundred years.

How many people will be on Earth in a hundred years? How many of them will be reading? Will any of them read print literature? And how will they receive Margaret Atwood’s until-then sealed-away and unread novel?

These future readers and their future world seem so out of grasp, so tragically distant. Yet that’s only relative to the average human lifetime, or to the duration of an individual human consciousness. Perhaps some of today’s infants will live to read the Atwood novel that we’re all being denied; those of us aware of it right now will not. But on a geologic time scale, a historical time scale, even in relation to the lifetime of a tree, those 100 years are nothing.

It reminds us of the resources that go into making the books we know and love, buy and sell, recycle and leave to crumble on bookshelves. The amount of time that goes into making a book extends beyond the writing and publication of the story; it starts with the trees — and the plastics and inks and animal hides and e-book components I don’t know the names of. In the event of any major catastrophes, a printing press has been placed in the Future Library to ensure that these books, no matter the technologies of 2114, can and will be printed on paper.

Before 2114, only the names of the authors participating in the project and the titles of their works will be displayed in a section of Oslo’s Deichmanske public library, although the manuscripts will be sealed away in boxes and stored in the very same room. It remains a mystery what exactly Atwood — and the as-yet-unannounced authors — will write for these future readers. Paterson has stipulated only that the works deal with the themes of “imagination and time,” with the hope of conveying something about our moment in history to their distant audiences. The very secrecy of the project is intriguing, and Atwood fans certainly feel cheated. I’ve had conversations with friends about how desperately we wish we could read her novel, or at least know what it’s about, and I’ve heard some lament what a terrible idea this withholding is.

After getting over the initial shock of being denied a book by a favorite author, I realized that the cleverness of Paterson’s concept is that we will never know. What makes Atwood’s writing so incisive — and entertaining — is her ability to take our current problems and anxieties (including, but by no means limited to, war, corporatization, climate change, genetic engineering; in sum, the power humans wield and are subjugated by) and project them onto a dystopian future. Her visions are frightening, but seem frighteningly possible. I imagine that the readers of the 22nd century will still have access to Atwood’s “classics,” already read by a century of bookworms. Her long-published work will provide evidence of the zeitgeist of our era. But the works anthologized in the Future Library, those will be written for the future readers, as a message to them. We know Atwood as an author who speaks to the contemporary reader in a prescient voice from an imagined future. We should trust her especially to communicate honest truths of our present to the unknown readers of the future.

As much suspense as I’m in right now fantasizing about what Atwood will write, I am also excited about the moments in which hot-off-the-press manuscripts will be opened, long sealed-away words read for the first time, secrets revealed, stories passed on. I must also remind myself of the ever-lengthening list of books I want to read, an uncountable number of them never to be checked off. This forthcoming Atwood novel is just another to add to my personal collection of unread literature. Many already-published Atwood works remain on that list of mine; getting to them seems infinitely more possible than making it to the year 2114. I even start to doubt my claim that I’m an Atwood fan, considering that I’ve only read four of her novels. We all live for stories — some we’ve known by heart since childhood, others we’ll begrudgingly remain ignorant about. We are fated not to know our ever-unstable future; time continues ever onward; stories have longer lifespans than we do.

Beyond the 100 anthologized works, the Future Library Project tells a different story that we will be able to follow, even if we don’t make it to the end. Paterson, Atwood, and even we have believed its audience into being, and as each contributing author is announced, yet another chapter will unfold.

This post may contain affiliate links.