India and Pakistan turned 67 on August 15 and 14, respectively. In 1947, both countries were born as independent republics, their surgical boundaries defined by religious demographics. Pakistan (“the land of the pure”) was claimed in the name of Islam, to be governed by the Muslim League under the leadership of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and India was deemed secular — albeit an implicit haven for Hindus and Sikhs — under the Indian National Congress led by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi. The treacherous and craven decision of the then-imperialist Britain to not reveal the official boundaries until August 14, and hastening the process of partitioning the subcontinent, exacerbated the communal violence, which claimed over one million lives. Resorting to guesswork, Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus frantically tried to assess if they fell on the right side of the religious divide right up until independence day.

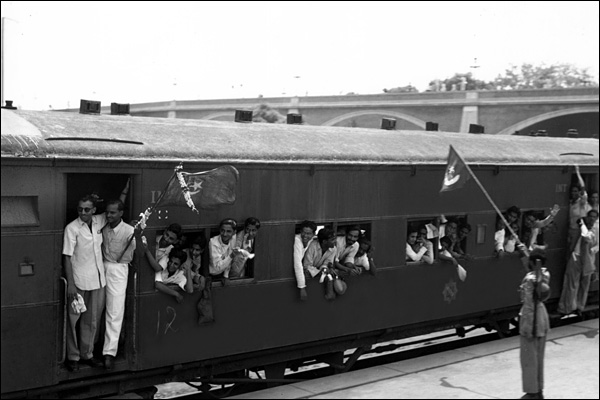

When the English left India, the exit was swift and severely uncharitable. After presiding over a century of oppression, the British did little to safely mobilize the over 14 million that were displaced because of the segregation.

As is the case with most dramatic movements of ethnic cleansing and massacres in the name of religion, the impetus was largely political. The partition of India has been astutely analyzed in the political context, engaging the aspirations of the national power players — like Jinnah and Nehru — and Britain’s strategic moves to evade accountability. But the way in which it eviscerated the people of their humanity and morality, political strife relaying an inconceivable degree of malevolence in an otherwise harmonious society, is not as easily graspable.

***

Saleem Sinai, Salman Rushdie’s protagonist in Midnight’s Children (1981), would also be 67 years old on August 15. Midnight’s Children, the winner of the Booker of Bookers, grappled with the idea of the uniquely dysfunctional independence granted to the Indian subcontinent. The novel accounted for the tectonic implications of the partition on India and Pakistan’s future through political events — taking place over 31 years post-independence — that reasserted the communal fault lines. Rushdie’s masterpiece is probably the most widely-read novel that deals with the partition.

But there are two other, not-as-celebrated novels written in the English language that offer trenchant commentary on and are essential to understanding the tragedy — Bapsi Sidhwa’s Ice-Candy Man (1992, retitled Cracking India in the US) and Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan (1956).

Both writers were born in British India and, post-independence, they wore different nationalities. Sidhwa is a Pakistani-Parsee — Parsees are Zoroastrian Persians who migrated to South Asia — and Singh, who passed away in March this year, was an Indian-Sikh.

These novels differ from Midnight’s Children as they are situated in the thick of the partition. The temporal span limits itself to three acts. These include: an Indian society where indigeneity takes strong precedence over theocracy; the sudden fear of un-belonging being co-opted by radical elements and the civilian-turned-marauder participating in the decimation of the other; the immediate aftermath of the reckoning.

The main characters in Ice-Candy Man and Train to Pakistan possess unique strains of morality, each self-serving and peculiar to their personal situation. How each moral vagary is manipulated and absorbed into a larger, unrelated conflagration fueled by geopolitical motivations, partially addresses what haunts some of the survivors of the partition today.

Singh’s story is set in Mano Majra, a fictional village in Punjab, while Sidhwa plots hers in the city of Lahore — one of the major cities of Pakistan post-independence — in Punjab. (Bengal and Punjab were the two provinces that were cut across and were consequently most susceptible to riots.) In both novels, the vibrant tapestry of both urban and rural India from within Punjab is highlighted by the inclusive diversity.

The writers draw from the quirks of their own ethnicities — Khushwant Singh employs the ribaldry that is characteristic of the Sikh community and is mostly channeled through the novel’s hero, Juggut Singh, while Sidhwa’s comedic elements are borrowed from the idiosyncrasies that define Parsees. Sidhwa also explains the neutral attitude of her people during the partition, suggesting it behooved them to be invisible (the Parsee community is also rapidly dwindling in India) as historically, that’s the promise they made to a ruler when seeking refuge in the Indian subcontinent. Thus, like the Christians, the Parsees were, in a way, immune to the communal violence. While Khushwant Singh doesn’t bring this up in his novel, Sidhwa also suggests that the Sikhs were manipulated, and incited by the Hindus against the Muslims.

***

Sidhwa’s narrator is Lenny, an 8-year-old girl who belongs to a privileged Parsee family and spends most of her time with her ayah (nanny). At home, Lenny is privy to the discussions of the elite. In one definitive scene Lenny’s parents are farcically convivial — entertaining their guests over dinner with inoffensive racist jokes — while trying to evade serious talk of the socio-political tumult that’s building up around them. But the guests, a Sikh called Mr. Singh and an Englishman, who is an Inspector General of Police, spark the friction, as they debate India’s sovereignty.

“Rivers of blood will flow all right!” [the Englishman] shouts, almost as loudly as Mr. Singh. “Nehru and the Congress will not have everything their way! They will have to reckon with the Muslim League and Jinnah. If we quit India today, old chap, you’ll bloody fall at each other’s throats.”

Mr. Singh retorts: “Hindu, Muslim, Sikh: we all want the same thing! We want independence.”

Outside home, Lenny accesses another reality, that of the less-privileged working class, mostly represented by her ayah’s various admirers which includes the “Ice-Candy Man,” a seller of ice popsicles. The religious and racial differences are less pronounced amongst these men. In the first act of Sidhwa’s novel, the backdrop of the partition is identified in Lenny’s home, and less by her interactions with ayah’s friends.

Initially, Sidhwa chooses not to name — as it would give away their inherited faith — some of these characters, using the child’s simple, occupational characterizations — “ayah,” “ice-candy man,” “masseur” — to refer to them, thus keeping their religious identities hidden. In this period, their more individualistic qualities endear the reader to them. But when the politically-charged conflict starts to permeate the lower classes, these characters begin to speak in terms of religion, revealing that the ayah is Hindu and Ice-Candy Man is Muslim.

***

Khushwant Singh’s study of morality engages a host of characters that help explicate the social construct in the village: a bureaucrat, a communist social activist, a petty thief, and a murderous pack of bandits.

Juggut Singh is a Sikh rogue who is in love with the Muslim cleric’s daughter in the village. He is at loggerheads with another prominent gang known to terrorize the village. Juggut is wrongly accused of a crime — looting and killing a wealthy businessman — that the other bandits committed.

Educated in London and a comrade, Iqbal Singh is antithetical to Juggut. He comes to Mano Majra looking to allay any Hindu-Muslim conflict that might have surfaced. But Iqbal is not needed in the village where Hindus and Muslims coexist very peacefully, and their problems have more to do with the burglaries and gangsters. Mano Majra’s status quo is telling of certain parts of the country that didn’t recognise the religious divide in the same way that the political intelligentsia did.

In Train to Pakistan, Khushwant Singh also takes a subtle swipe at some of the leaders of the freedom movement, and the frequent hunger strikes and imprisonment, as they were key to acquiring political clout. When Iqbal, as an outsider, is arrested on suspicion of having killed the businessman, the activist appreciates the political currency he might earn by being put behind bars.

“But he was not a leader. He lacked the qualifications. He had not fasted. He had never been in jail. He had made none of the ‘necessary’ sacrifices. So, naturally, nobody would listen to him. He should have started his political career by finding an excuse to court imprisonment.”

Much like Sidhwa, Khushwant Singh highlights the distinction between the motivations of the political class and the proletariat during the partition.

In the Ice-Candy Man and Train to Pakistan, the violence is essentially triggered by the “ghost” trains that pull up at the station with dead bodies of migrants. In Sidhwa’s book the train is full of slaughtered Muslims, whereas in Singh’s the train carries butchered Hindus and Sikhs.

In both villages an engorged river is described, made turgid not only by the monsoons but also by innumerable human carcasses.

The bandits in Khushwant Singh’s village join the radical forces, not because they are driven by religious sentiment but because they see it as an opportunity to raid and plunder Muslim homes with impunity. Hukum Chand — the magistrate and deputy commissioner of the village — chooses not to interfere and lets the vengeful hysteria take over, while Iqbal Singh is seen assessing the situation and realising the futility of trying to break up the furor, as he would simply become one of many casualties. Khushwant Singh’s hero, Juggut Singh, is the only one who goes against the tide and dies while trying to foil the bandits’ plan of butchering the Muslim passengers, including his Muslim lover, on a train leaving from Mano Majra for Pakistan.

Sidhwa navigates more complex terrain with her story. As Lahore goes up in flames, many of Sidhwa’s characters, particularly from the lower classes, become active participants in the conflict. Sidhwa’s anti-hero, Ice-Candy Man, who is in love with ayah, comes to Lenny’s house searching for her with a mob of Muslim fanatics. When Lenny’s mother insists that ayah is not home, Ice-Candy Man tricks Lenny into telling him where she might be, exploiting Lenny’s trust by suggesting that he had come to protect ayah. Lenny’s unwitting betrayal is deeply subtextual. The child’s gullibility is metaphoric of the susceptibility of working-class civilians like the Ice-Candy Man, who became easy targets, blinded and herded by the religious bigots. This sentiment is best expressed by Lenny’s soliloquy when she realizes the gravity of what she has done:

“I am the monkey-man’s performing monkey, the trained circus elephant, the snake-man’s charmed cobra, an animal with conditioned reflexes that cannot lie…”

Ice-Candy Man ends up marrying ayah and affirms his deepest devotion to her, after she has endured rape at the hands of men from his community and has been pimped out in the red-light district of Lahore. At this point, the Ice-Candy Man inspires revulsion and compassion in equal measure. He lives in denial about his bestiality during the partition, while helplessly hoping his pleading will make amends, and ayah would see that he truly loves her.

Both books explore this flawed humanity, the fabric of which easily came undone with the slightest tug at its frayed ends. And throughout, Sidhwa and Singh acknowledge the complicity of “both sides” — subtle nationalistic biases only weigh in when the political power players (Jinnah, Nehru, Louis Mountbatten) come up — as Singh establishes the naked truth in the first few paragraphs of Train to Pakistan:

“The fact is, both sides killed. Both shot and stabbed and speared and clubbed. Both tortured. Both raped.”

This post may contain affiliate links.