In 1997, I was the eight-year-old kid sister to my then nineteen-year-old big sister. I loved her clothes, I loved her lipstick, I loved the nail polish she lined across her dresser, and I definitely loved the stack of comic books she kept on a shelf in her room. So when she handed me a Supergirl issue, the first of its series, I learned to love that too. The cover framed the front view of a pouty-lipped girl, holding a skateboard across her chest. It was so cool. I knew the crush on Linda Danvers had taken full fruition, once I plastered a collage of the series on the front cover of my high school agenda. Her parents fought with each other every night, while she in turn fought their disappointment with her. This was a perfect sad girl story for my 90s sad girl tween heart. The mark of true fandom, after all, is relatability. The only problem, then, was that Linda Danvers was white.

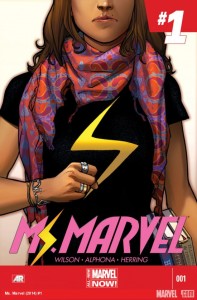

In 2013, Marvel introduced its first female Pakistani super heroine: Kamala Khan as Ms. Marvel. It’s a comic book about a sad girl, with a mother who fears for her sexual temptations and a father who pushes discipline on her. In the first issue of this series, Kamala is taunted by her white peers at school, who either knowingly (or possibly worse yet, unknowingly) scrutinize her “otherness” to the point of triggering an identity crisis, wherein she imposes a type of self-hate on herself. Kamala, frustrated at this disconnect from her peers (her inability to drink alcohol, to go out to late parties, etc.), runs away in the middle of the night. A sad brown girl questioning her identity after being made to feel less than; because a bunch of white kids and a bunch of older Pakistani adults needed her to be more of one of the halves she was composed of. Suddenly, I realized I did not want to relate.

In 2013, Marvel introduced its first female Pakistani super heroine: Kamala Khan as Ms. Marvel. It’s a comic book about a sad girl, with a mother who fears for her sexual temptations and a father who pushes discipline on her. In the first issue of this series, Kamala is taunted by her white peers at school, who either knowingly (or possibly worse yet, unknowingly) scrutinize her “otherness” to the point of triggering an identity crisis, wherein she imposes a type of self-hate on herself. Kamala, frustrated at this disconnect from her peers (her inability to drink alcohol, to go out to late parties, etc.), runs away in the middle of the night. A sad brown girl questioning her identity after being made to feel less than; because a bunch of white kids and a bunch of older Pakistani adults needed her to be more of one of the halves she was composed of. Suddenly, I realized I did not want to relate.

I don’t know if children who were born into their parents’ country understand the visceral reaction westernized, second- or third-generation children of immigrant parents have when put in proximity with their parents’ foreign, native territory. There are colored people all over the world who were born and raised in a western culture and thus are dubbed “basically white” despite the obvious contrasts in the color of their skin. White-washed is the more colloquial term for this, tinged with a horror one associates with the self-denial involved in the actual bleaching of skin. Much has been written about how such conceptual washing occurs, really, to comfort white people, and colors us a shade of pale familiar and subdued and safe. You are ethnic when deciding where the best Indian for dinner tonight is. You are ethnic when your potential marriage is up for discussion.

You are white and safe in high-waisted denim jeans and an American Apparel bodysuit.

Hilariously enough, you will be qualified as most suitably ethnic in the same singular moment your whiteness is challenged. When a friend notices a book perched on a shelf in your home. A travel guide to whatever foreign land your mother or father was born in. There are those who laugh at you, because “you are that, why would you need a book?” Your response, a sheepish grin, an unavoidable feeling of embarrassment, followed by a non-committal or explanatory “yeah.”

Thing is, while this moment is supposed to be a testament to the bi in your bicultural identity, I wonder if those looking at you, whoever, not necessarily white, but whose gazes other you all the same, understand the gut-wrenching feelings banked somewhere deep in your seemingly indifferent “yeah.” Skin colors aren’t equipped with a genetically predisposed, expert-like understanding of religion, politics, history, or anything else happening in the part of the world you were explicitly and decidedly removed from — the information that’s the stuff of tourist books. But your environment was coded from the second your parents didn’t speak or look or smell like those of your friends on your first day of school. Your relationship to that land started there, at home around the dinner table, in your broken use and understanding of the vocabulary shared fluently between your blood relatives. It’s not that these aspects were necessarily generous, things of beauty — families never are, let alone history. It wasn’t a relationship founded on love, but on a more powerful experience; a visceral, naturalized, gut-like understanding.

Suddenly by way of an inquiry regarding a book on a shelf, this understanding, your lived reality, is challenged. While a handful of white friends have photos of them standing in front of the five must-see monuments in the capital of your mom’s native country, you’ve still never even read that book on your shelf. The name of this country barely evokes the slightest sense of nationality in you, and yet all the same, it carries a possessive intonation. You already know you are nothing like your family back home, but they are your family. “Back home.” Glide your fingers to trace the letters of the title on your guidebook, and somehow it feels like it belongs to you.

It’s in the specific oils your mom used to wash your hair, or the cheesy foreign pop songs you made fun of with your siblings and cousins, and the family dinners when aunties didn’t say “how’s school?” but really casually said “you got fat.” In the cupboard full of ethnic grocery staples, and in an inability to read foreign text on the signs of stores, but the recognition of the letters all the same. On the weeknights where adventurous dinners constituted of drive-through McDonald’s or delivered pizza. In the way your white friends invited their first girlfriends or boyfriends over for dinner, while you tried to avoid telling your parents that you even knew someone of the opposite sex.

Even those who insist on denying any relationship to a culture other than their Western upbringing still recognize familiarity in shades of brown. Denial and self-hate are still rooted in recognition, after all. I have an Indian friend, and when he was younger, people would inquire about his ethnicity and he would shake his head and say “I’m black,” and frankly it was a more than fair statement to make. His brown was of an especially dark shade, and all of us who knew him associated him with his drawn out “Shieeeeeeeeets.” Of course these elements themselves do not make for a black person, and of course he went home to a mom in a Sari, but as far he was concerned, born and raised in Canada, his first words were hip hop, because here in the West, at least that was a language he could explain. Sure, yes, he was black, but his last name was still Patel.

And what of privilege? What does white privilege mean to a poor brown kid surrounded by rich Indian friends? The answer lies somewhere within the parameters of both classism and relativism. Poor in the West, but in possession of technologies foreign and admired to your cousins “back home.” Home, where they manufactured multiple copies of your pleather skirt or skinny jeans. Apparently the middle class collapsed a while ago, which makes me poor. The kind of poor that’s wearing a $90 Zara dress, anyway. The rich kind of poor. A decent closet for the latter half of a life, and one plane trip across the ocean on the whole. A girl with a MacBook, and a last name that raises eyebrows.

Years ago — and if you ever read something from me again, this will be a recurring fact — I visited Bangladesh, my parents’ country and my country, for the first time in my whole twenty years of existence. I packed a suitcase with a collared sleeveless shirt, skinny jeans, a couple of sweaters, a Zara top, and one maxi skirt for conservative care. This means that when I first planted my feet on Bangladesh soil, I visibly stood out. I have a dramatic and wonderful photo captured by my dad, wherein I am sitting on top of a camel and its instructor in the middle of Jaipur, India, looking like a fucking hipster. I packed the clothes I wore to shows and cafes back home. “Back home.” And on this trip, a couple native Bengalis worked for us. They looked at me and saw a modern girl. On the second day of our trip, we attended a bridal party. One of these workers, a sort of personal assistant for my father, sat on the couch in our home waiting for my mother and I to get ready. When I walked out of my room in a long, white, lahenga, my father looked at me, raised an eyebrow, reached his arm out in my direction with his palm up, turned to the assistant and said, “Meet my Bengali daughter.”

To be a human existing seems complicated enough as is. However, if you fit into one of the many labels of oppression, a different type of complication develops. It’s one that doesn’t seem like it ought to be inherent to being alive. Upon closer inspection, in fact, it would seem unlike a complication, and more so a kind of worldly beauty, akin to the wacky mechanics of science, or the illogical consequences of love. It becomes better than complicated; it becomes non-linear, circumstantial, different, complex. I suspect this will be the overarching lesson the Kamala Khan’s of the world come to learn; to live not one half of two, but two halves of one.

There is nothing more infuriating than being denied of or asked to prove your lived experience, and it is in my experience that I have lived in both these lands. It is a quiet kind of oppression to have the world constantly demand an explanation for your complexity. The truest truth is that the root of all racism comes from a fear of the unknown. I spent my teenage years alienated just like everyone else, but with the specific belief that I was the only person in the whole world (teenagers!) who occupied multiple spaces in this simultaneous way. My white friends thought it was weird that my parents were so overprotective. I had no brown friends because I listened to Belle & Sebastian, and that meant I was too white to relate to. So what was I really? What am I now? I guess, I’m a girl who understands that there is no consistent and inherent qualitative experience to being who you are. Because “you are that.”

Photo thanks to Sruti Islam. Sruti Islam tweets at @weirdera

This post may contain affiliate links.