Less than three minutes into Top Gun (1986) rumbles “Danger Zone” by Kenny Loggins and with it, perhaps, the greatest montage of the American workperson since Flashdance (1983). Floating somewhere in the Indian Ocean is the USS Enterprise, the crew of which resembles a swarm of drosophila flies, covered as they are from head to toe in dark clothing and thick mitts and helmets with giant ear-buds. These men are seen through a shimmering lens — as if the camera itself is a fiery jet engine — pumping fists, jogging in slo-mo, rolling up tubing, dragging and yanking massive black hoses, crab-walking, saluting no one in particular, talking on phones like quarterbacks after the big throw, patting each other on the backs, twirling their fingers and pointing and jacking up peace signs.

Cut to a room aboard the Carrier. There are blinking red lights and super-sized computers and maybe seven people just standing around. In the background is Commander Tom Jordan (James Tolkan), call sign “Stinger.” Jordan has a prominent chin that seems to drag his entire face down, the most hairless thing I’ve ever seen. He is a tough character. “Who’s up there?” Jordan growls to a sweaty airman with a tiny headset.

“Cougar and Merlin — and Maverick and Goose,” replies the airman.

“Great,” says Stinger, mock-happily, standing with hands on hips: “Maverick and Goose.”

Enter Maverick, as though he’s heard his name spat from Jordan’s lips. Maverick is piloting an F-14, mouthpiece dangling like an ignored seat belt. His first words of the movie are spoken to his best friend and Radar Intercept Officer: “Talk to me, Goose.”

* * *

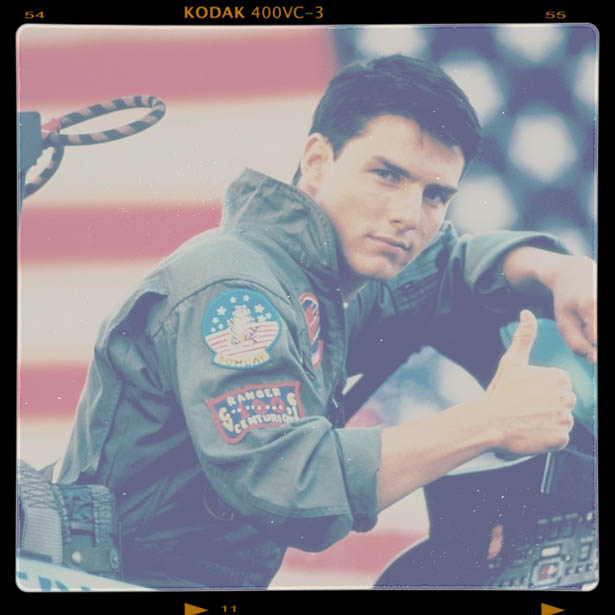

During one of the first combat exercises at Top Gun, Maverick (Tom Cruise) descends below 10,000 feet (something he is expressly told not to do) to “kill” Jester (Michael Ironside). Because of this infraction, Maverick and Goose (Anthony Edwards) are called into the commander’s office to be reprimanded. Their Top Gun commander Viper (Tom Skerritt) explains to Maverick — and also to Goose, but sometimes Goose has this beautiful way of drifting into the background, 80s porn star mustache and all — that he “broke a major rule of engagement.” Maverick and Goose are dismissed, and in their absence, Viper asks Jester’s opinion of Maverick: He’s a “wild card, unpredictable, flies by the seat of his pants,” says Jester. Presumably, this is what Viper was thinking as well or else he wouldn’t have asked for his second’s opinion. But still, Viper can’t help but be impressed by Maverick’s flying: “He got you, didn’t he?”

Once established in Miramar, Maverick becomes a sort of demi-god. By virtue of being the movie’s protagonist, he’s more developed, and thus, seemingly different from the other elite pilots, whose stories we know little about except how they intersect with Maverick’s. This creates the impression that Maverick is more like us, more developed, more human. In truth, however, he is no more like us than any other pilot at Top Gun, including de facto villain and Maverick’s rival Iceman (Val Kilmer).

Iceman “flies ice cold, no mistakes,” Goose tells Maverick over drinks and beer nuts. The bar, straight out of Miami Vice, is teeming with white jackets and buzz cuts. You can almost smell the tonic, sealing up nicks from tight shaves. Like Maverick’s, Iceman’s reputation precedes him; Iceman appears seconds after being discussed, his ears burning. “You figured it out yet?” Ice, chewing the hell out of a beer nut, asks Mav. “What’s that?” Mav says, taking a swig from his bottle and avoiding eye contact. “Who’s the best pilot,” Ice replies.

In the previous scene, the airmen are seated in a dark room (the blinds are drawn) being lectured on the importance of air combat maneuvering by Jester. The room resembles a cozy, independent movie theater except instead of a projector screen there’s a white board and instead of movie-loving patrons, the room is filled with slippery-faced, cigarette smoking airmen in beige suits. In the background, something is resembling the video game Counter Strike is playing on a monitor, and there are plaques, flags, and black and white photographs all over the walls. When the blinds are opened as Viper walks in, we get a better look at who we’re dealing with. Iceman wears a gargantuan blue-tinged ring and works a silver pen around in his fingers. He stares straight ahead, says nothing. Maverick’s head is on a swivel, on the other hand, which prompts Goose to ask what he’s doing. “Just wondering,” Maverick says, “who’s the best.” While this is going on, Viper explains about a particular plaque, which, coincidentally, lists the best pilot in his class from previous years. “Do you think your name’s gonna be on that plaque?” Viper addresses the room, rhetorically. “Yes, sir,” Maverick responds. Slider and Iceman grin like buffoons. “That’s pretty arrogant — considering the company you’re in,” Viper tells Maverick. “Yes, sir,” replies Maverick. Viper, his mustached face collapsing on itself, says, “I like that in a pilot.” Now Maverick and Goose grin like buffoons.

Entering Top Gun, Iceman is considered to be the best; Goose tells Maverick (and us) as much. Not only that, but Iceman appears unblemished: blonde hair, blue eyes, 6 feet, a feminine softness to his face and exceptional posture. Compared to Maverick — brown hair, 5’8” at the most, made Top Gun by the skin of his teeth — Iceman is clearly superior. Such a contrast is intended to further humanize Maverick. Both men are clearly arrogant, but Maverick, we’re supposed to believe, is justifiably so; he is arrogant only in order to compensate for whatever Iceman has that Maverick doesn’t. (In reality, there is nothing Iceman has that Maverick doesn’t). Regardless, we’re expected to give Maverick a pass, to applaud his bravado while condemning Iceman’s hubris.

By the next scene, at the bar, both Maverick’s and Iceman’s bulges have become more prominent. Their dicks are razor-sharp and preparing to sword fight. Wearing his aviator sunglasses (the only one wearing sunglasses in the dimly-lit bar), Iceman leans against a wall in the corner; a woman with a big blonde poof and strapless dress rubs against him. Iceman faces forward. No words are exchanged between the two, and Iceman’s face suggests such attention is business as usual. Meanwhile across the room, Maverick is attempting to woo Charlie (Kelly McGillis) by serenading her with “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” the 1965 Righteous Brothers hit single: evidently a popular song among the Navy boys because the fellas in white and beige and blue sing back-up vocals without any direction from the lead. By the end of the song, nearly the whole bar is in on the singing, and Charlie has no choice but to invite Maverick to sit beside her and have a drink. Forgive the pun when I say that the bar proves to be filled with wingmen.

Maverick’s fleeting insecurities giving way, as the scene calls for it, to his daredevil machismo is simply too obvious to be believable. We understand that Maverick has been constructed in such a way as to resemble a real person, like a much too perfect clone exhibiting only the black and white aspects of a human being. The truth is that we live much of our lives in the gray area, between fight and flight.

But Maverick doesn’t.

Maverick’s character, as it is, helps us experience the movie in the way we wish to experience it, satisfying whatever we were looking for when we chose a ‘high-octane’ flick like Top Gun from the shelf or at the box office rather than its contemporaries Gandhi or Driving Miss Daisy. The by-product of Maverick’s living his life at the extremes is that his character is never in danger of convincing us that he’s a real person with real feelings.

This is incredibly freeing for viewers like me.

Watching Maverick, I’m more selfish than empathetic. I don’t have to feel as he feels. When he’s high, I’m happy, and when he’s low, down in the dumps depressed, I can still be happy. I know his failures are not my own. Throughout the movie, I use him, guilt-free, to do whatever bidding I desire, whatever fantasy I wish fulfilled. What I’m saying is that Maverick is effective as Top Gun‘s centerpiece because he makes a better window than door.

* * *

My favorite scene in the movie, maybe one-third of the way in, is the beach volleyball scene, which takes place at what has to be the only spot in Southern California nowhere near a beach. This is the best part of the movie, hands down. Kenny Loggins’ “Playing with the Boys” humping and hipping and bleeping like an arcade game. What I love most about this scene is that it represents my idealized version of playing with my friends. Maverick and Goose and Iceman and Slider (Rick Rossovich) are really just like my buddies and me. Except, of course, they’re much, much cooler.

These Top Gun guys are cut and shirtless (besides Goose), oil slick and barefoot. At one point, Slider actually howls at the moon, though it can’t be more than a few hours past midday. Their pecs flicker to the beat of the music they aren’t supposed to be hearing. Iceman spins the volleyball on his index finger like a Harlem Globetrotter. On one side of the net, there is Maverick and Goose: on the other, Ice and Slider. It’s like the battle between my high school football and baseball team that I always prayed would take place, but it never did because the jocks hung out with each other.

The teams are well matched during the opening volleys. But that’s what’s expected and so has all the excitement of watching your friend play Pong in slow motion. What really excites me is when Maverick and Goose appear, suddenly, to be on the ropes, their backs against the wall, at the wrong side of ‘game point,’ it would seem. Iceman’s spike has just sent Maverick diving to the sand, who stands back up without a grain of sand on him. From this point on, Maverick and Goose are Misty May-Treanor and Kerri Walsh-Jennings, three-time Olympic Gold Medalists in beach volleyball and masters in the art of last name hyphenation. A spike here, an ace there, and the good guys have it. The win is then reinforced with the Top Gun High Five.

Albeit a romanticized representation, this is, we’d like to believe, how someone like Maverick (a romanticized figure himself) hangs out with his boys, and in a sort of call and response to this scene, I can’t help but imagine my best friends and me getting down on some beach volleyball a la Top Gun: Joe and I on the near side; J-Henn (our nickname for the other Joe) and Dan across the net. In this fictional scene, we’re all roughly 17 years old. Joe is the only one in good shape, the recent protein-smoothies putting him just north of scrawny. His shirt is already off, his chest and back virtually hairless. I’m peeling off my soggy shirt, which is sweat-logged and chafes my nipples. Unlike my friends, I’m at least ten pounds overweight and the only part of my body without hair is the inside of my mouth. J-Henn stands about 6’2”, four inches taller than me and Joe and six inches taller than Dan. J-Henn is sickly pale and of Irish-heritage (last name Hennessey) so he keeps his shirt on because otherwise he will burn to a crisp. It’s because of this, I like to think, that he spends so much time indoors. Dan’s real name is Thang; he’s Vietnamese. Besides appearing undernourished (he is not), Dan is light brown and has a concave chest. His nipples are dark-brown, which amuses us pink-nippled white boys. His black hair is tall and stiff — in fact, he has the best hair of the group. His shorts are baggy and slung-low, revealing boxers. Dan thought that when I called him up for a game of volleyball, I was joking. All of us have a good case of bacne.

Despite our looks and at least half of the group’s general distaste for athletics, I can imagine us being sick at volleyball. I think of Dan crouching low to the ground (channeling his old karate days, “hi-ya!”), dropping down for a perfect set to J-Henn, and J-Henn like a streak of white lightning leaping into the air and ripping a thunderous spike, the ball landing just between the outstretched hands of Joe and me, both in mid-dive, muscles flailing against our skin like kenneled dogs. I think of J-Henn, then, throwing back his head like he’s in a shampoo commercial, roaring at the sky, fists clenched. I think of Joe and me making an improbable comeback worthy of a documentary film, capped with our own special high-five. After the game, I can see our silhouettes marching into the sunset — or to wherever we parked our Kawasaki’s — to the beat of every hit single of the decade simultaneously. Instead of what we were, in other words, I think of four hard-bodies, covered in oil, moving in the sand like we were born in it: nowhere to go but full-speed ahead. Kicking ass and taking names.

* * *

Goose’s death is a reminder, although short-lived, that Top Gun is not all glitz and glamour, chicks, and slick, six-pack abs. Top Gun is not, in other words, outside the governance of the real universe. Nothing says that more matter of factly than the accidental death of a loved one. But it’s much too late in the movie for this sentiment to ring true, which I suppose is the point. Top Gun didn’t win the 1987 People’s Choice Award for its accurate representation of the fragility of human existence. The opposite, actually.

How Maverick responds to this tragedy is a pivotal aspect of the film. If death is the great equalizer, then it’s how a person responds to death — or the idea of death — that separates one from another. Maverick has every right to shut down, to feel sorry for himself, to binge drink or carb-load. Will he swallow antidepressants? Begin recording his innermost thoughts in a journal per advice from a new age, military-appointed therapist? Or will he bounce back as the same old Maverick, Goose’s death a temporary setback? How does someone like Maverick cope with loss, in other words?

Charlie, for one, pushes Maverick to move on. She finds Maverick sitting alone in a bar, presumably day-drinking. His hands cradle his head. Surprisingly — or not so surprisingly — Maverick’s glass contains only ice water. He’s both everything and nothing we expect; his unpredictability is what’s so predictable.

“It’s not your fault,” Charlie says, taking a seat beside him. She has seen the evidence from the flat spin that killed Goose; what happened has been ruled an accident. “You’re one of the best pilots in the Navy. What you do up there — it’s dangerous,” she says, leaning closer to him, trying to find a way in. “When I first met you, you were larger than life. Look at you. You’re not gonna be happy unless you’re going Mach 2 with your hair on fire, you know that.”

“It’s over. It’s just over,” says Maverick.

“To be the best of the best, it means you make mistakes and go on. It’s just like the rest of us,” Charlie explains.

But of course it isn’t like the rest of us at all. Not when you fly a jet plane for a living and your best friend has just died in your arms.

Regardless, Maverick responds as Charlie (and we) need him to. He doesn’t retreat or withdraw; he doesn’t journal or knit or crochet. Instead, he does something we could only ever dream of doing if somehow found in his situation: he saves the day. Responding to a surprise attack, Maverick flies brilliantly, shooting down several enemy planes and saving Iceman’s ass to boot. He brings the people to their proverbial feet, which is how I’ve been watching since the opening credits. Ready for takeoff.

Merrill Sunderland is an MFA candidate at George Mason University, where he serves as the editor of the literary journal Phoebe and works for the annual Fall for the Book Festival. Like a moth to a flame, he’s always been drawn to the big air, facial hair, and can-do attitude of the 80s.

This post may contain affiliate links.