Two weeks after Elliot Rodger killed six people in Santa Barbara, four days after a student at Seattle Pacific University shot and killed another student, and two days after an anti-government Bonnie and Clyde killed two Las Vegas police officers, President Obama conducted a question-and-answer session with David Karp, the CEO of Tumblr, who posed questions to Obama that were sent in by people online. A UC Santa Barbara student asked what the president was going to do about the country’s endless backdrop of high profile massacres.

Obama expressed a frustrated but earnest remorse that is seen somewhat rarely in Washington — the psychological grip the NRA holds over the capital often has made legislators cower away even from gestures of plain sorrow. He called his failure to enact legislation after the Newtown massacre “my biggest frustration so far.” It was a remarkable statement if only because the idea that gun control would have a top legislative priority has come to feel like the waste of a top legislative priority. Michael Bloomberg and his merry band of mayors may still be roaming the countryside on a quixotic quest to stymie the flow of domestic arms, but everyone else knows the NRA has won.

“We’re the only developed country on Earth where this happens,” Obama said. As a rhetorical tool, this-only-happens-in-America has proven to be ineffective, even creating blowback against the snooty liberal notion that we should be like everyone else. Obama has largely focused his tenure on attempting to shift uniquely American ways of doing business — our uniquely expensive and inefficient health care system, our unique denial of global warming, our unique apathy for railroads — towards the industry standards of modern developed nations. Pointing out that these systems are particularly ineffective in our country spurs opponents to double down on American exceptionalism: We are, the sentiment tends to go, the only country that has fully realized the Enlightenment born ideal of the individual, and we curtail unique rules to our unique individualistic destiny.

Considerations of the Enlightenment today seem like anachronism. Today’s popular conception of American individualism owes little debt to John Locke or Immanuel Kant or even Thomas Jefferson, no matter how many mentions of feeding the tree of liberty with tyrants’ blood. Tea Party-style hyperindividualism’s apologist du jour is now officially Ayn Rand, who, although long admired by a backwoods bohemian libertarian core, has seen a popular resurgence as her work has become the intellectual touchstone of the new conservative era. David Brat, who unseated the previously unassailable House Majority seat held by Eric Cantor, authored the paper “An Analysis of the Moral Foundation of Ayn Rand” while an economics professor at Randolph-Macon College, and is arguably the most explicitly Randian acolyte set to hold a Congressional seat. Rep. Ron Paul, during a campaign stop in the 2008 primaries, discussed with supporters how Atlas Shrugged had been an early fosterer of his libertarianism. Rep. Paul Ryan is known to hand out copies of the book to staffers.

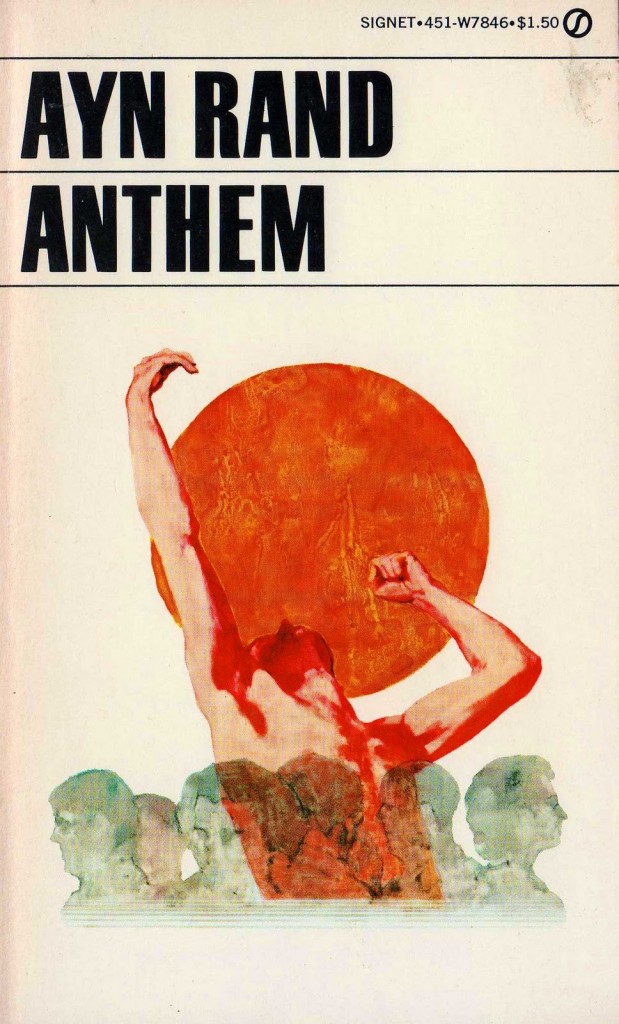

Rand wore the clothes of philosophy (she dubbed her constellation of ideas Objectivism, referring to it as “the philosophy I invented”) but never really mastered its nuance. For Rand and her adherents in the electorate, collectivism is life’s archnemesis, roll credits. Calling her position “individualism” seems too flaccid to describe the abhorrence the Russian-born writer had for water safety departments and the pooling of resources for public goods. Although The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged remain her two-piece canon, her loathing of collectivism was most succinctly novelized in Anthem, her dystopian novella about Equality 7-2521, the numerically named protagonist who rejects the despotic collectivism of his USSR-style state circa The Distant Future and transforms his identity into that of the free-willed Prometheus. The book ends with a singular word, “EGO,” which a fully individuated Prometheus hangs over his door. “EGO” foreshadowed the same intellectual corner cutting of modern conservatism and its rallying cries like “Free Markets, Free People” that turns economic liberalism into a catchy dictum, no further explanations required, slogans which have been unleashed like an invasive species of some new kind of oxygen. “EGO” floats in the sky over America in giant bubble letters made of clouds.

Nowhere has hyperindividualism (or neo-individualism, or uberindividualism, or EGOindividualism — whatever we call it, it’s more virulent than it was before) reached more of an apogee than in the NRA. The once regulator-friendly organization threw its weight behind large-scale gun control frameworks in the 1960s and, since its managerial sea change in the 1970s, has worked tirelessly to chip away at the very legislation it helped to create. The current NRA shares little more than a name with its earlier incarnation, and it has earned a reputation of not only being one of the most intimidating lobbying groups in Washington, but also one of the most fundamentalist, opposing everything from additional serial numbers on guns to one-a-month handgun purchase limits.

Gun control advocates argue that the entire logical foundation of New NRA rests on the organization re-ratifying its own version of the Second Amendment — “A well regulated Militia” is now written in strikethrough. Discerning whether the Founders intended individuals to have unfettered gun access is a quicksand of constitutional law, but regardless, the new interpretation is a seismic shift from its predecessors. DC v. Heller, the landmark case that stuck down the District’s regulations on the possession and owning of handguns, inspired the same baffled result by gun control advocates as Citizens United did for opponents of over-moneyed elections. The notion that the right of gun ownership, in whatever quantity, firmly adheres to the individual, cued jaw-dropping among scholars, a landmark case not only in Second Amendment law, but also in the legal evolution of hyperindividualism.

The EGOists, however, face the irony of rationalizing the military, an entity whose funding dollars have long been considered sacrosanct by the right and which depends on subverting individuals into members of a uniformed collective. This irony was not lost on the military itself. By the beginning of the millennium, the military was trying to shed the dehumanizing reputation it had developed since Vietnam. In 2001, after twenty years of “Be All You Can Be,” the US Army changed its slogan to “Army of One” and rolled out its debut commercial during a Thursday night episode of Friends. The New York Times described the ad:

The commercial features a lone corporal running across the barren terrain of the Mojave Desert at dawn. At one point, a squad of soldiers runs past in the opposite direction; later, a Blackhawk helicopter flies by overhead. But the corporal never veers from his solitary path, panting under the weight of his 35-pound pack as his polished dog tags glint brilliantly in the rising sun. “Even though there are 1,045,690 soldiers just like me, I am my own force,” the corporal, Richard P. Lovett, says.

Irony solved. No longer did a soldier feel he had to suppress his EGO in order to serve his nation. Individualism wasn’t given up in the military, it was actualized.

But Richard P. Lovett’s rank was still judged by superiors in a standard protocol, his arms were standard issue paid for with public dollars, his adversaries were a faceless mass targeted by teams of government and military bureaucrats, those abominable storm troopers themselves militarized against the EGO. He can walk against the flow of combat-zone traffic all he wants, but Richard P. Lovett still sounds a lot like Equality 7-2521.

One no longer had to just think they were their own force, as Corp. Lovett put it — they had to become their own force. They had to draw up their own declarations of war, stock their own arsenals, choose their own enemies. Just barely submerged beneath the NRA’s spoken positions is the idea that the government should not have a monopoly on violence, a repudiation of the very idea of a functioning state — that instead, the ownership of violence is to be dispersed by those who choose to hold it, for whom violence is a sating of the EGO.

Of the mass public shootings of the past decade, Elliot Rodger’s was, in many ways, the most scintillating, like a violent, sexually charged piece of clickbait to his own YouTube videos. Rodger left behind a Mein Kampf-esque manifesto that detailed the tyranny of sexless life and, in his final YouTube video, launched a personal declaration of war against “sluts” that refused to have sex with him. Even his dubbing of the incident as his “day of retribution” sounded like an operation code name. The Las Vegas shooters had a vague yet explicit antigovernment bent, but Rodger’s shooting was, in many ways, the most traditionally warlike.

Rodger’s rampage shared the same nihilism as every other Great American Massacre in recent history, a selfishness turned into solipsism, forced to process throughout life that satisfying that selfishness is humanity’s highest virtue, that it is its own army, and that there is absolutely nothing preventing it from loading up on handguns and assault rifles and extended clips to retaliate against some group it feels has attacked it. This is more than the diagnoses of white male privilege that portray a spoiled shooter jilted by unfed entitlement. More than that, the shooters are coaxed by a sense of post-national duty to their own individual micronations. By the time the message has been digested and laws removed to potentiate individual army-building, it is too late for caveats that all the allowances to buy unlimited arms and exist in an cocoon of the self does not mean you can kill people. The killing is already too well scaffolded.

“It happens now once a week, and it’s a one-day story. There’s no place like this,” Obama said at the question-and-answer session. By the time of the Seattle shooting, I had already become exhausted by studying the details of Rodger’s rampage and only browsed the circumstances of the Seattle killings. And by the time of killings in Las Vegas, I only read the headline and the lead. I may have thrown up a link to the story on Facebook without comment, and I didn’t read about it much further until writing this piece. At the time, I was apathetic, as if trying to keep up with every bombing in Iraq, and I skipped ahead in the paper for another story about something else happening in the world, as I imagine others did as well. A conflict can only go on for so long before the readership of every newspaper is collectively weighed down and a little bored from war fatigue.

This post may contain affiliate links.