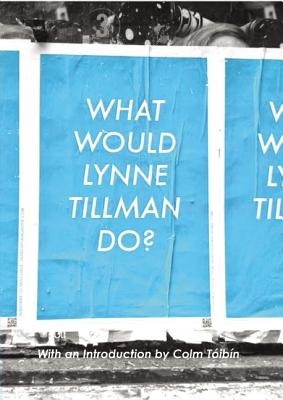

[Red Lemonade; 2014]

[Red Lemonade; 2014]

Fiction writers’ opinions on current events have a basic, ironic appeal: Credentials, qualifications — they have none. Have they ever been “on the ground”? Oh, here and there, perhaps. Granted special access to a subject? Are you talking about the self? No? Then no.

This is not to diminish the worldliness of Lynne Tillman. It is to say that she has in common with all good writers a singular mastery of rhetoric. The times are drunk on expertise: the newsperson, the academic, the IT guy. The first thing I should like a talking head to do is fumble with a mic and ask, Can anyone hear me? On which follows the idea of the writer as pro skeptic: should anyone hear me? In an interview with Paula Fox, in lieu of a question, Tillman assures her that she’s a great writer. Tillman is aghast that anyone, especially Fox herself, didn’t know that. The same thing is obvious with Tillman, and it doesn’t take more than a few sentences in order to tell. Her quality as a writer is some function of what is and what is not obvious to Lynne Tillman. “I don’t trust experience, even if it has shaped me.” Which is one of the most trustworthy things I’ve read in a while.

The essays in Lynne Tillman’s What Would Lynne Tillman Do? come in sections alphabetically ordered, inscrutably, by subject or tone (“M is for Mordant”). In the end, WWLTD? seems serendipitously structured as a quest to find fans of Two Serious Ladies, the would-be classic by Jane Bowles. Tillman professes her love for it, pushes it on people, notes parallels. In the essay “Nothing is Lost or Found,” Tillman sets out to include Paul Bowles in an anthology of American ex-pats. She’ll tell you a secret: an interested editor, after talking a little shop, shows her his tasteful nudes. What follows concerns copyright law, a deathbed swindle, and the FBI reading the mail. The essay is palpably excellent. It demonstrates a good ear and a knack for skipping to the good part of the story (sex, poison). It’s a work of literary criticism that emphasizes enthusiasm, though she’s hardly incapable of playing straight: “Though the whole has never existed and the Real is not available, these illusions nourish fiction.” And it’s written with quickness, intelligence, and presence; after reading her observe the shy, handsome laugh of Paul Bowles, I had the feeling, perhaps strange and dumb, that I knew with a critical certainty that a person was writing.

I would be remiss not to point out the collection’s perspicacity. In WWLTD? there are outtakes from her book on Warhol; a consideration of Ryan Gosling “acting real” (watch him pin up matchbooks in a retirement home in Blue Valentine); essays on the futurists, Nan Goldin, and she is told that Osama bin Laden is dead. She is ambivalent about the label “Downtown”, that it means something to you. “You — I — never see yourself or your contribution that way.” A 1995 internet piece avoids hilarity. She notes the overuse of quotations in memoirs of Multiple Personality Disorder. She imagines the genre “unpopular culture.” John Waters writes “Cult Filmmaker” on his income tax forms.

The interviews included in WWLTD? feature Tillman as questioner rather than subject. The most striking conversations are with two, actual, serious ladies. The first is the poet Etel Adnan, born and raised in Lebanon, telling of the origins of her pacifism in an incident “as bad and worse” than the Sabra and Shatila massacre:

Tel al-Zaatar is a neighborhood in Beirut, where 20,000 people, not all Palestinian but mostly Palestinian, lived basically underground. The Phalangists and their allies attacked in ’76. Maybe the fighters in the camp had some advance notice and left . . . There was only one well, so women would go there for water. Maybe 20 to make sure one got back; they were surrounded by snipers.

The second serious lady is Paula Fox. Tillman talks to Fox about researching a new novel. It will have something to do with the Cathars, a Christian sect of way-sub-Templar contemporary interest. A Cathar, unlike an extant Christian, did not pick and choose holiness from sin: the whole physical world is fallen. It belongs to Satan. Nothing is supposed to be here. It was a belief that had them hunted down and massacred. They made last stands in hillcrest castles in the south of France. Where, Fox says, some of the novel will go:

. . . back to 1321, when heretics occupied some small villages in the Pyrenees. They were the Cathars, and they were, like the Albigensians, completely wiped out by the Dominican priests. I’ll tell you one story that I use: A Dominican priest was describing a village late at night to some horsemen, a gang, and one of the crusaders tells him there were only 20 heretics left in the village. The total population was 200. The Dominican priest said, “Kill them all. God will know his own.”

Maybe you’ve faintly heard of Lynne Tillman. But of course you can hear of her. “At the Microphone” is Tillman trying her hand at a micro-essay: two paragraphs on the 1975 “Schizo-Culture” conference, often credited with opening America to French theory. The day had brought lectures by William Burroughs and R.D. Laing. Then John Cage goes to the stage and begins to speak, unamplified. The crowd tells him to use the microphone, that they can’t hear him. To which Cage says, “You can, if you listen.”

M.C. Mah is a critic and novelist with work in The Nervous Breakdown, KGB Lit Mag, and The Rumpus. He lives in Brooklyn.

This post may contain affiliate links.