On YouTube you can watch Jonathan Franzen, born in Illinois, say he can’t decide whether or not the Midwest exists, a question he goes on to explain by way of a paradox. When someone, who could be from anywhere, remarks on the essence of the Midwest — its innocence, or friendliness, or preservation of values — he returns that the Midwest does not exist. But on the occasion when others, now it seems to me more likely to be themselves lapsed Midwesterners, suggest the Midwest is an invention, or a set of ideas that no longer apply, he counters with precisely the opposite. “Have you ever watched a Midwesterner get on the subway in New York City?”

Lately I’ve been getting on the subway in Shanghai, where I seem to face even greater obstacles than my status as a Midwestern provincial. Expatriation has brought me closer to understanding a trope among exiles, like Joyce, who move abroad and have their thoughts colonized by home, their distant host cities providing only minor background detail — I’m thinking of the line in Ulysses about Paris’s “lemon streets.” We often argue the exile’s intention is to gain perspective, but surely that doesn’t always hold true. I came to Shanghai thinking I would spend much of my time paying close attention to the city around me, but instead my thoughts have turned with stubborn consistency to America, the Midwest, and my hometown, in Iowa, of 10,000 people. I’ve begun, for example, to read Willa Cather’s epics of the prairie in cabs, as the city slides by outside the windows, and on the subway, squeezed among a crowd, in a curious attempt to broadcast that my gawking, my bumbling, and my confusion are located not only in my foreignness, but also in my provincialism.

I’ve noticed that we don’t call each other “provincials” anymore. At one time provincials populated the world of the Bildungsroman, where the rural hero would eventually conquer the metropolis while also, and more quietly, resigning to its demands. I’m in part paraphrasing Fredric Jameson: “Once upon a time, when provinces still existed, an ambitious young provincial would now and again attempt to take the capital by storm.” Provinces, Jameson claims, no longer exist, and whether or not we agree, things have certainly changed. Franzen’s thoughts are rooted in a shifting historical experience that’s not the same as Willa Cather’s.

Part of Cather’s appeal is how she documents that changing Midwestern history in space. Her 1918 masterpiece My Ántonia is split into five books, and in each book the narrator has moved: from the prairie to the small town to Boston and to New York. But Boston and New York are only alluded to in passing through exposition; even after the narrator has moved away, the novel’s set pieces remain in Nebraska. These late sections detail a summer vacation and a visit after a long absence, and as he returns to the Midwest he feels the difference with a worldly nostalgia, unburdened by illusion. The highway has come, washing away some of the markers of his childhood, but he can still remember “the rumbling of the wagons in the dark,” and feel again the boredom and repression of Blackhawk, Nebraska. “On starlight nights I used to pace up and down those long, cold streets, scowling at the little, sleeping houses on either side,” he recalls, and his youthful frustration’s mature parallel comes when he stops by town again, years later, on a business trip. After an afternoon, he thinks: “I scarcely knew how to put in the time until the night express was due.”

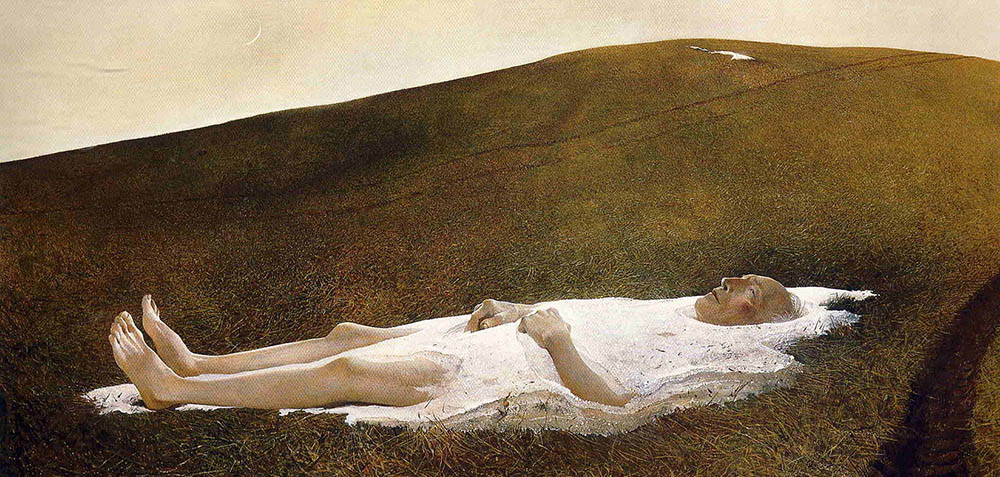

It’s this last thought — the small oppressiveness — that I often associate with my hometown. But reading Cather, whose writing is attuned to prairie life’s dull, restricted quality, but equally to its beauty, and always to its seriousness, has helped me better know my home. To live in the prairie, or in the small-town Midwest, is for Cather to give something up, but also to be able to notice how “along the cattle-paths the plumes of goldenrod were already fading into sun-warmed velvet, grey with gold threads in it.” In her novels, as in history, growing up in the Midwest is an accident of necessity, a place you stumble to from Bohemia, decide to put up with after a sad departure from Sweden, or hopelessly wind up in after a stint picking oranges in Florida. And yet it’s an accident that immediately becomes worthy of sustained thought.

Cather was born in Virginia in 1873. At age nine she moved to Nebraska, where her father was a terrible farmer. By age 23 she had left. She lived first in Pittsburgh and then in New York, and though she would return to the Midwest, she would never again live there. I’m getting this from two introductions to old Bantam classic editions, one of which, by Stephanie Vaughn, contains the following Cather quote: “As everyone knows, Nebraska is distinctly déclassé as a literary background; its very name throws the attuned critic into a clammy shiver of embarrassment. Kansas is almost as unpromising. Colorado, on the contrary, is considered quite possible. Wyoming really has some class, of its own kind, like well-cut riding breeches. But a New York critic voiced a general opinion when he said: ‘I don’t care a damn what happens in Nebraska, no matter who writes it.’” I don’t think to laugh at the joke is to neglect the anxiety.

By the time she wrote My Ántonia, her voice had developed into one of American literature’s most mature and sophisticated. The novel looks back on a Midwestern childhood without condescension and with a special novelistic clarity, but what stands out is not Cather’s intimacy with the Midwest, nor her acquired urban knowingness, but something in between, an estrangement from both New York and the Midwest matched by an attachment to both. Edward Said observed how Conrad’s writing, for him typifying literary exile, has about it “the aura of dislocation, instability, and strangeness.” In Conrad’s fiction the idea of the exile is mysterious, anguished, and unresolved, and in Cather’s stories of partial exile distance and melancholy spread throughout. But finally in Cather, like a coda, arrives a sense of contentment.

* * *

Not so for the Midwest, where existential doubt still lingers. Do the provinces no longer exist? And is Franzen’s uncertainty explained away by history? Such questions obliquely restate Franzen’s own. The key, I think, is not only in history, or in the flattening of history and homogenization of culture. Yes, people in the Midwest now consume the same media as people on the coasts — indeed around the world — receive it with ever-decreasing delay, and are under equally complex governmental and commercial management. But the problem of the midwest involves not just history but space, with the at times indistinguishable difference between the transformative effects of space and time. This is where Cather’s “ability to read time in space,” as Bakhtin said of Walter Scott, is indispensable. Families move from the far-flung prairie to the neatly arrayed small town, and as they move you get a sense of historical development, of the prairie being tamed and routinized.

It’s the taming that’s distinctively Midwestern, as opposed to the vast adventures of the West, and this modest process brings us closer to understanding the Midwest’s essence by allowing us to glimpse it as part of history. In the beginning of Cather’s 1913 O Pioneers!, a family of immigrants, just having moved to the prairie, convey the anxiety that “the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness.” Today, on the contrary, certain agriculture zones in the Midwest should be counted among the most industrial places in America. The Midwest has transformed, whether or not it contains an essence we’re still familiar with.

For Franzen the essence of the Midwest seems to be a prolonged innocence. I would also suggest that it involves an open-minded moral seriousness, along with a good-natured happiness distinct from humor, or at least comedy. (Comedy in Cather’s prairie novels is nonexistent—people “laugh immoderately,” but you don’t.) Still, Franzen’s skepticism is correct. To try to name the essence of the Midwest, as I’ve just done, is to summon shades of doubt — and just as we’re encountering that doubt new aspects are being added to the Midwest’s regional identity. It wouldn’t be hard to list changes happening to the Midwest today: immigration and demographic shifts, the decline of industry in the north and the total spread of agribusiness in the plains, the receding importance of Chicago and other cities as financial centers, and so on. Looming above all of these, however, is climate change, with its odd mix of obvious influence and apparent unfathomability.

Cather, yet again, is useful here. Even to someone like me, who has spent nearly his whole life in the Midwest, Cather’s writing can seem exotic and uncanny, a revealing impression about the Midwest and its transformations. Familiar place names billow out lush, foreign-sounding natural taxonomies, mixed with things I’ve long experienced, like the “stimulating extremes of climate.” This is a personal and contemporary reading, but it’s also one that tempts me to go further. Perhaps the profusions of nature in Cather hint at her escape from the prairie and move to New York, her mind muddled and excited by the slips and inventions that disturb and delight those who reflect on home after leaving. You can imagine this subdued kind of exile to have about it a sense of enormity or its opposite, but either way it led to a looking back. Did the prairie become exaggerated along the way? Did it attain a higher brilliance of color?

This is mostly a matter of style and adjective; today the rich Midwestern plant life that once existed is relegated to obscure corners, or perhaps extinct. But Cather’s descriptions don’t only conjure up the replacement of the plains by the agriculture industry. Reading these nature passages, or noticing how Cather records the Midwest’s transformations, I’m brought to mind of the advance of climate change and the way it promises to preside over a new series of changes, both conspicuous and obscure, social and psychological. Doubtless soon many of the remaining species of Cather’s childhood will be resigned to the fate of the prairie, disappeared long ago.

The prairie novel unsurprisingly vanished shortly after, collapsed into a sub-branch of the historical novel; before long, new types of literature and forms of imagination will be necessitated or exhausted by climate change. I’ve begun to wonder if trying to make out the extent of the environmental crisis, of its varied and fainter effects, almost demands an ironic circuitry: you have to begin somewhere unexpected or minor and then bring yourself back to the existential urgency of today’s environment.

The indirectness of my thinking here at least seems to say as much: first life as a Midwesterner in China, then Cather, then climate change. At once everything leads to climate change, and yet, at least for many of us from the northern hemisphere, seemingly nothing does. There is a flood here, we notice, and a drought there, and while these phenomena are clearly related to climate change, it’s hard to draw a straight line between the two, and easy for many to ignore. Meanwhile, during these last few winters Midwesterners have grown hilarious, very unlike their prairie-taming ancestors captured by Cather, and tell climate change jokes: climate change will just mean that we can all finally stop shoveling our driveways.

People in Shanghai tell jokes too: my Chinese tutor offers consolation: the pollution will strengthen my lungs. The environment here is awful in an obvious way, and while it’s not a direct result of rising temperatures it does come in large part from burning fossil fuels. Waves of smog come in bursts, hanging like stationary mist, and certain days it’s all anyone talks about, sometimes with outright anxiety and sometimes with a levity that has something more disquieting lagging behind it. People wear cheap surgical masks that don’t do anything and that they know don’t do anything. They monitor the air quality on their phones like it’s their email. I occasionally check it, too, though I have no idea what the numbers mean. 300 I know is bad, but I get the impression it’s more or less the norm.

It’s clarifying to live in a place where the effects of carbon emissions are this visible, if only to see how people go about their days living alongside it. The rich and middle class buy air purifiers; the poor are forced to put their hands over their mouths. This is a version of what we’re all beginning to do: living with a level of environmental degradation that will at this rate eventually become unlivable. The novelist Norman Rush has said that that the novel’s real problem is not its declining number of readers but the “environmental crisis, a mosaic of threats to human flourishing that grows more complex by the day,” which makes “the social struggles traditionally addressed by political novels seem parochial.” He was writing as part of a symposium on politics and the novel, but to me the mysterious work of the novel in regard to climate change seems less about politics and more about calm, diverse reflection, though ideally they might be hard to separate. My parents tell me in Iowa it continues to snow.

William Harris is a writer living in Shanghai.

This post may contain affiliate links.