The photographer Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub on the day of his suicide.

Suspicions have been aroused by rising sales of the digital edition of Mein Kampf. Readers must have something to hide. We are being warned that our reading habits are under surveillance, with covert purchases of Hitler’s book provoking comparison to popular e-reader sales of the soft-core melodrama porn Fifty Shades of Grey. But the average consumer downloading Mein Kampf in 2014 hardly functions under the same threat as the poet Robert Lowell did in concealing his copy inside a dust jacket of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mals in World War II Paris.

In an era of frenetically dispersed political techno-messaging, something old-fashioned attends the thought that Hitler’s master plan is summarized in one book. But no one really reads Mein Kampf. And, in picking up Hilter’s profane manifesto, one would find little insight into the psychological complexity of the twentieth-century’s most notorious villain.

Journalists trying to understand the rise in popularity have cited explanations like the one offered by a Jewish leader who asserted, “The spike in e-book sales likely comes from neo-Nazis and skinheads idolizing the greatest monster in history.” But Mein Kampf has long been available for free download at such sites as hitler.org or archive.org.

Neo-Nazi factions very well may be determined to access Mein Kampf on their e-readers; but how concerned are extremist groups with dissembling their interest in fascist propaganda? It’s easier to imagine an unpremeditated purchase of Mein Kampf than an inquisitive skinhead reassured that the anonymity of gaining covert access to the book has obviated the need to furtively thumb though its pages. That brisk sales of Hitler’s polemic on Amazon ranking number one in the propaganda and political psychology section)and iTunes have drawn such wide media attention speaks to the publishing industry’s frothing obsession with revenue, best seller lists, the market, big ticket authors, and so on. Purchasing Nazi memorabilia on eBay or costly first editions of Mein Kampf — one sold for $42,000 in a 2005 auction — reveal a more distilled fascination with the Third Reich than do sales of Hitler’s polemic for less than one dollar.

Not surprisingly, sales skyrocketed when The National Socialist Party achieved electoral victory in 1933. But few members of the Nazi elite actually took the trouble to read it. One British statesman of the period dismissed any notion that the “rantings of Mein Kampf were a practical manual” of Hitler’s conduct; a German industrialist remarked, “Not even the most rightist circles in Germany ever took such hysterical ideas seriously.”

That technology affords new avenues of exposure to inflammatory material raises the predictable debates about censorship. And, arguably, the ephemerality of e-reader editions may indicate less dedication to the book being purchased. Books are no longer thrown on a pyre, pulped, or bowdlerized; they are simply made unavailable for download or deleted. E-book readers are less collectors than consumers. The intimacies of book possession — provenance, scribbled marginalia, signs of dedicated attention, dog-ears, tears, worn covers — are nonexistent in the downloaded book. The digital download allows books to be effortlessly “searched.” Mein Kampf is most likely searched for its most incendiary anti-Semitic passages — not to read with social conscience but to scrutinize specific passages that affirm reactionary political positions. The uncritical reader is well served by technology.

One can only read Mein Kampf with the agonizing knowledge of Hitler’s Final Solution. Ready access to hate speech of all categories is a quintessential modern reality. The robust industry of cinematic representations of Hitler and the Holocaust is received with far greater ease than the notion that anonymous readers are out there consuming Nazism unstylized or devoid of comforting theatrical effects. Mein Kampf strikes a rare balance of being at once tedious and inflammatory, with boggling excesses of paranoia and hate. No fascist aesthetic serves to make Mein Kampf palatable. Mein Kampf does and should provoke many different conversations, whether as a first edition complete with a poster of upcoming Nazi events, a pulp “people’s version,” or a digital download. It is either cynical or hopeful to believe that readers are unlikely to read Mein Kampf cover to cover.

To purchase Mein Kampf at all is a moral event — whether in seeking to understand how an event so piteous and heinous in the extreme ever occurred or in pursuing pseudo-scientific evidence to justify prevailing racial hatreds. The morally correct reason for reading Mein Kampf in the 21st century is to make the incomprehensible comprehensible. To “never forget.” To awaken conscience. Few readers have the appetite for such a well-intentioned undertaking.

Thus Mein Kampf, filled as it is with statistics, allegorical exaggeration, and undigested paroxysms of hate, is not a book anyone really reads. The recent rise in digital sales of the book does not mean that people are actually getting through the some 700 pages of Hitler’s reflections on the “leering grimace of Marxism” or “the Jewish peril.” Since its first publication in 1925, critics have roundly dismissed the book as grotesquely verbose, riddled with lies, fantasies, and the projections of a megalomaniac. Questions of authorship even plague the book. The heavy revisions and rewriting required just to get Mein Kampf into readable condition were met with deep disapproval by Hitler. He had one of the book’s editors, who had eliminated “the more flagrant inaccuracies and the excessively childish platitudes,” executed by a “special death squad.”

Mein Kampf lacks all of the conventional justifications for reading an autobiography: the rawness of the revelations, the encounter with the ego behind the mask of a man, the hope for a degree of intimacy. There is very little here to gratify the insatiable modern preoccupation with biographies containing confessions, “reality,” psychology, and “the true story.” Mein Kampf can only be taken as a crude, rambling diatribe by the man responsible for the supreme tragic event of modern times. It is much less policy manual than autobiographical fever. And, indeed, Hitler presents very few unique ideas. Wagner, Nietzsche, Darwin, and even Henry Ford set many of the ideological precedents, but his pathology and fury are unrivaled.

Traditionally, many critics have rather single-mindedly positioned Mein Kampf as a book one is either for or against. Representing extremes of inhumane behavior and a program of brutal action, Mein Kampf of 1925 is a calculation of viciousness to come. Mein Kampf of 1945 is a prophecy fulfilled, a mass of ideologies instrumentally enacted; Mein Kampf of today, as some see it, offers the menacing possibility of future duplication. There is a tenacious fear that reading Mein Kampf will enlist or embolden a significant body of readers to embrace Neo-Nazi convictions. But even Hitler lacked faith that the average reader could appreciate the book, as he explained in Mein Kampf: “Their brain is unable to organize and register the material they have taken in. They lack the art of sifting what is valuable for them in a book from that which is without value.”

Mein Kampf is a vitriolic narrative as well as an artifact, a piece of its unholy author. Having Mein Kampf on the shelf sends a message about one’s readerly commitments. A quick Google image search locates several photographs of people with Mein Kampf held in a firm grasp. Many of these images frame the “reader” in an implied state of irony. Posing for photographs while mockingly engrossed in Mein Kampf points to the very absurdity and unlikelihood of such attentiveness. One cartoon has Donald Duck in Nazi regalia studying Mein Kampf.

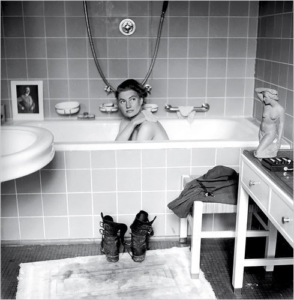

In May 1945, while billeted in Hitler’s Munich apartment on assignment for Vogue magazine, the American photographer Lee Miller photographed an American sergeant simultaneously reading Mein Kampf — one of Hitler’s own copies — and using the Führer’s “hotline” to Berchtesgaden while lounging on Hitler’s shabby couch. The soldier’s very presence in the apartment broadcasts the supreme failure of the plans mapped out in the book he is reading. His insouciant air drains the book’s talismanic power.

The vicissitudes of Mein Kampf’s sales history have irrefutably reflected interest in Hitler as a leader and legislator of atrocities. The earliest clothbound editions included posters; two volumes were eventually combined into one; publishers distributed the books as school primers on racial science; civil servants were instructed to read it; a Reich Minister suggested that all newlyweds receive a copy. The book also appeared in special editions and dozens of languages (including Braille). A deluxe Mein Kampf was bound in blue leather with gold flourishes and the blade of the sword gracing its cover.

Very little of the original published text changed, excepting necessary diplomatic deletions of references to a “French hydra” and plans to “wipe out France” made to avoid antagonizing France’s Vichy government. Copies in 1930s France were impossible to obtain anyway, although some questionable editions could be purchased from pornographic book dealers. The story of its American publication and reception is complex and problematic in its own way, with various disputes over copyright, battles over the authority of unabridged editions, and debates about inciting hatred versus serving the pubic interest.

Houghton, Mifflin & Co secured the American copyright, which it maintains to this day. The South German state of Bavaria holds the European copyright until 2015, and printing Mein Kampf there is illegal — but owning or distributing extant copies is not. Citing that it “sent the wrong signal,” Bavaria recently scrapped plans to produce an annotated critical edition of Mein Kampf ahead of the book’s entry into public domain. Bavaria’s decision not to fund an annotated version suggests that an explicated Mein Kampf is a more threatening Mein Kampf. That an edition full of historians’ interpretations, scrupulous research, and instructive commentary would energize Germany’s far-right activists is questionable, although anxieties in Europe seem much more legitimate given its more politically represented racist extremism.

Between the two poles of scholars reading Mein Kampf for material about National Socialism and the neo-Nazi contingent seeking a manifesto to incite hate and implement new plans for Aryan domination, lies a mass of readers downloading the book out of casual interest. In 1930s Germany, Hitler’s readership was vast. That, in its historical moment, the book served as a lethal source of invigoration and validation is without question. That an e-book version will convert readers to neo-Nazism seems much less likely.

Hitler would have admired the e-book. Enthralled by the power of technological innovation to promote National Socialism, Hitler embraced all tools to mediatize and disseminate his work. As he explains in Mein Kampf, he had much greater faith in the seductive power of the visual than in the written word.

Ultimately, the intentions of the Mein Kampf reader cannot be divined. But to assume that increased sales portend an approaching storm front of racial hatred is too simple. Public attention is easily steered by media frenzies. Reports that Mein Kampf sales bespeak an upsurge in the corruption of our sensibilities are producing considerable handwringing. This phenomenon, however, should also be part of the conversation about how reading itself is undergoing radical change.

Annalisa Zox-Weaver is a freelance writer and editor. She is the author of Women Modernists and Fascism: Female Modernists and the Allure of the Dictator from Cambridge University Press. Her recent publications include “Gertrude Stein Facing Both Ways,” in Women, Femininity, and Public Space, Ashgate, forthcoming; co-author with Wendy Martin, “Adrienne Rich: Poetry of Witness,” in The Cambridge Companion to American Poetry, Cambridge University Press, forthcoming; “The Photo Album as Reconciliation: The Books of Albion,” in The Photograph and the Album: Histories, Practices, Futures, Museumsetc., 2013.

This post may contain affiliate links.