In 1997, my father rented an office north of downtown San Antonio on Broadway Street. As he prepared to transition out of the rural ranching business, he adorned his office walls with Ansel Adams photographs. Adams produced few images of the Texas landscape, preferring the ostentatious vistas of Yosemite and the grimaced trunks of Joshua Tree. Even so, Ansel Adams’ photographs speak to the sensibilities of certain Texans, those who treasure their state for its tremendous size, its dynamic history, and the devastating grandeur of its landscape, its characters, and its mythos.

My father shared this office building with a man named T.R. Fehrenbach. Mr. Fehrenbach, who passed away on Sunday, December 1st at the age of 88, was a widely read Texas historian, an apostle of grandiose Texas mythmaking and one of its last public intellectual holdouts. Most notably, Fehrenbach contributed the 1968 classic Lone Star: A History of Texas and The Texans, which clocked in at over seven hundred pages, to the state’s historical canon. Up until August of 2013 he was also a regular columnist for the San Antonio Express News, where he acted as resident dreamweaver and champion of the mavericky tough-love conservative ethos harnessed by George W. Bush and Rick Perry, and emulated by a subsequent generation of the pseudo-libertarian right.

Fehrenbach and my dad shared a love for Texas’ scale, but they had their differences. My dad had spent his early life in the suburbs of Austin and, an heir to many generations of open range reveries, started his own ranching operation in the nineties. Eventually, he grew weary of the crushing heat, of the anxious dependence on rain.

So he moved to the Alamo City and hung his Ansel Adams prints in T.R. Fehrenbach’s building. And when Fehrenbach wrote a column decrying the laziness of Mexican ranch hands (it speaks to the perseverance of the white Texan establishment that one could read such things in the late nineties, and indeed today, in a city with one of the largest and most politically active Latino populations in the country) my dad felt obliged to reply. He wrote a letter to the editor in which he called Fehrenbach’s racism uninformed, accusing the latter of “ranching from his desk” only a few dozen feet away.

The next day, as my dad tells it, he was headed to his office when he heard a stern, gravelly voice call out, “Day.” He turned to see Fehrenbach gnawing on a cigar.

“Yes, sir,” my father answered, frozen at the entrance to Fehrenbach’s office.

“Point noted,” Fehrenbach said.

“Yes, sir,” my father replied, and the matter was never mentioned again.

In the stories they tell about themselves, white Texan men are reliably laconic. It’s an indispensable trait, integral to their legendary charismatic masculinity, balancing out their otherwise sheer flamboyance. No doubt that as my dad told me this story, on the occasion of Fehrenbach’s death, he was embellishing a bit to this effect.

***

The New York Times’ obituary section quotes T.R. Fehrenbach as having said, “Rangers, cattle drives, Injuns, and gunfights may be mythology, but it’s our mythology.” He declared this in an interview with Texas Monthly in 1998, the same year my father took him to task in the city paper, but the specifics of the instance hardly matter — Fehrenbach expressed this sort of opinion all the time. When he wasn’t growling tersely with a cigar clenched between his teeth he was given to smart-alecky provocation.

“The great difference between Texas and every other American state in the twentieth century,” he wrote in Lone Star, “was that Texas had a history.” Fehrenbach’s sense of humor is one strongly associated with Texans of his ilk; to the extent that one can generalize, this consists of bragging, stretching the truth, and bragging about one’s ability to artfully stretch the truth. “It ain’t braggin’ if it’s true,” my dad says to me in a mock twang much thicker than his own, “and it ain’t lyin’ if it spices things up.” The basic message of this comedic mode is that reality is subordinate to a colorful and usually self-aggrandizing story.

Thus, unperturbed by accusations of fabrication, Fehrenbach confessed to a level of untruth in his writing, even referring to his own work as “political science fiction” on one occasion. Evidently Lone Star grew out of notes sketched in preparation for “the great Texan novel,” which Fehrenbach set out to write after serving in the Korean War and graduating magna cum laude from Princeton.

Fehrenbach was a folklorist at heart. Even when he drew upon historical and anthropological work, and used them accurately and effectively, these were but threads in his grandiloquent yarn. He was interested less in traditional scholarship than in origin myths: cowboys and Indians, sheriffs and outlaws, cattle kings and crude oil and the splendid, providential bounty of Texan soil and civilization. The Southwestern Historical Quarterly put Fehrenbach’s flavorful anecdotalism nicely: “Fehrenbach is a highly interpretive and original writer, whose work rests on solid scholarship. His book ranges grandly across the disciplines from folklore to anthropology to history.” Highly interpretive. Rests upon. Ranges grandly.

Time has seen Fehrenbach’s abandonment by the academic establishment, but his work remains popular among connoisseurs of Texas epics. Fehrenbach’s 1974 book Comanches: The Destruction of a People was republished in 2003 as Comanches: The History of a People. A new round of editors dropped the “destruction” bit, judging it to be inaccurate and offensive to the fifteen thousand Comanche Nation tribal members living in the United States today. The newer, more politically correct edition of Comanches features a blurb by Larry McMurtry, author of Lonesome Dove and other Westerns, who emphasizes Fehrenbach’s talents as a writer and storyteller, if not quite as a scholar. McMurtry declares Comanches “a very good book. Like virtually all good books about the American Indian, it tells a tragic story, but unlike many of them, it tells it well.”

Indeed, Fehrenbach’s writing seems to have more in common with McMurtry’s fiction, in both method and disposition, than with the academic yield of the last two decades. The New York Times quotes a few contemporary Texas historians whose opinion of Fehrenbach appears ambiguous at best, probably restrained in the wake of his passing. They seem to regard Fehrenbach’s worship of white frontiersmen and his yen for hegemonic folklore as outmoded:

Professor Cummins, who teaches at Austin College in Sherman, Tex., acknowledged that “Lone Star” had come to be seen as a period piece written in “the context of his times.” He said, for instance, that Mr. Fehrenbach placed far greater emphasis on white frontiersmen than do today’s historians, who give considerable weight to the roles and contributions of women, Mexicans, American Indians and blacks…

[The] historical view has changed, said Paula Mitchell Marks, a historian as St. Edward’s University in Austin. A new generation of historians is marshaling modern analytical methods to move the study of Texas history “out of the 19th century into the 21st,” she said.

“We are certainly much more aware of race, class and gender issues and how they affected people in history,” she added.

While Fehrenbach’s prose is undeniably captivating, there’s something insidious about the way it naturalizes European dominance. For evidence of this impact, look no further than the first customer review of Comanches on Amazon, which commends the book for “describing the clash of cultures that occurred between red men and white and [bringing] home the inevitableness of this clash and the hopelessness of accommodating the Indian’s way of life.” The takeaway from Fehrenbach’s political science fiction, beyond the impression that Texans are eminently dashing and distinctive, is that the status quo is inevitable, that white frontiersmen were innately suited for positions of power.

With early Texas history unevenly documented and consequently somewhat up for grabs, many regional historical volumes flirt with heavy embellishment. The narrative cutting through most of this historiography is one of foreordained white male domination over the land and other people. Fehrenbach occasionally lamented this domination, but he ultimately saw it as an organic outcome of a war between tribes rather than the result of a systematic colonial program. His spellbinding semi-fictionalizations of Texas history have an air of Manifest Destiny about them, Texas envisioned as a promised land for an exceptional people. The state’s “closest 20th-century counterpart is the State of Israel,” he wrote in Lone Star, “born in blood in a primordial land.”

Make no mistake: Fehrenbach’s worldview was a hyper-racialized and fundamentally racist one. In Seven Keys to Texas he endeavored to distill the essence of the Texan consciousness, by which he unquestionably meant the white Texan consciousness. One of his central theories was that the frontier in Texas was more complex than elsewhere in America, because by the time white settlers arrived they had to deal with an unusual number of adversaries, and for much longer. In his estimation, this protracted frontier era generated the grit and tenacity we associate with white Texan stock characters, from the cowboy to the oilman to the faux-populist right wing politician (all men, de facto). He wrote:

The majority of true Texans… stem by blood or tradition from that vast trans-Appalachian trek that resulted in the wresting of North America from the wilderness, the Indians, and the Mexicans.

And it was this very struggle against pre-existing non-white populations that produced what Fehrenbach understood as essential or genuine Texanness:

Here Americans had to battle for predominance with a different nation and culture (the Mexicans), [and] face a far more dangerous type of warlike aborigine… Here the frontier lasted long enough to imprint itself thoroughly in the people’s consciousness, to fashion song and story, create a literature, affect folkways, and give birth to a culture.

Much of Fehrenbach’s work was an effort to exalt this narrowly defined Texan culture, to celebrate its song and story, its customs and folkways, its triumphs and setbacks. Unfortunately, this exaltation came at the expense of other Texan subjectivities, which remain in his work merely the backdrop against which authentic Texan consciousness was forged.

***

I come from a line of Texan fabulists and folklorists, of both the professional and kitchen table variety. My grandfather was a fellow of the Texas State Historical Association contemporaneously with Fehrenbach, and they knew and respected each other. My grandfather was also the director of the Texas State Archives throughout the sixties, and served as President of the Texas Folklore Society for a while. He wrote books with titles like Black Beans and Goosequills: Literature of the Texan Mier Expedition and Mines, Mules and Me in Mexico.

I value the narrative traditions I grew up with, and I mean to dance on neither my grandfather’s grave nor Fehrenbach’s. But the stories we tell, the rudimentary fantasies we entertain, beg reevaluation. The Texas history-cum-folklore traditionalists were engaged in two projects at once: the preservation of a genuinely interesting archive of white male history and the exclusion, the disavowal, of all other histories. Though these origin stories themselves are rich, the historical archive is poorer for their discernible allegiance.

I had the pleasure recently of drinking a few Shiner Bocks alone in a room full of my grandfather’s collected volumes of Texas history, and I can’t tell you how much delight I took in leafing through titles like Tall Talk from Texas by Boyce House, More Cowpokes by Ace Reid, West is West by Eugene Manlove Rhodes, Flaming Feuds of Colorado County by John Walter Reese, Famous Sheriffs and Western Outlaws by William MacLeod Raine and Texas: A World in Itself by George Sessions Perry. But these authors’ names are entirely reflective of the experiences elaborated within these books’ pages. What about the defeated and exploited, the footnotes in the Texas foundation saga?

A richer, livelier, more complex, more honest and fundamentally better regional historiography will compile their music and literature, and will document their tales of courage and loss. It will try to understand the consciousness their descendants have inherited from centuries of prosperity and, more often, struggle. It will — and indeed, as Fehrenbach’s New York Times obituary suggests, has already begun to — commit their stories to record alongside those Fehrenbach told with such charisma.

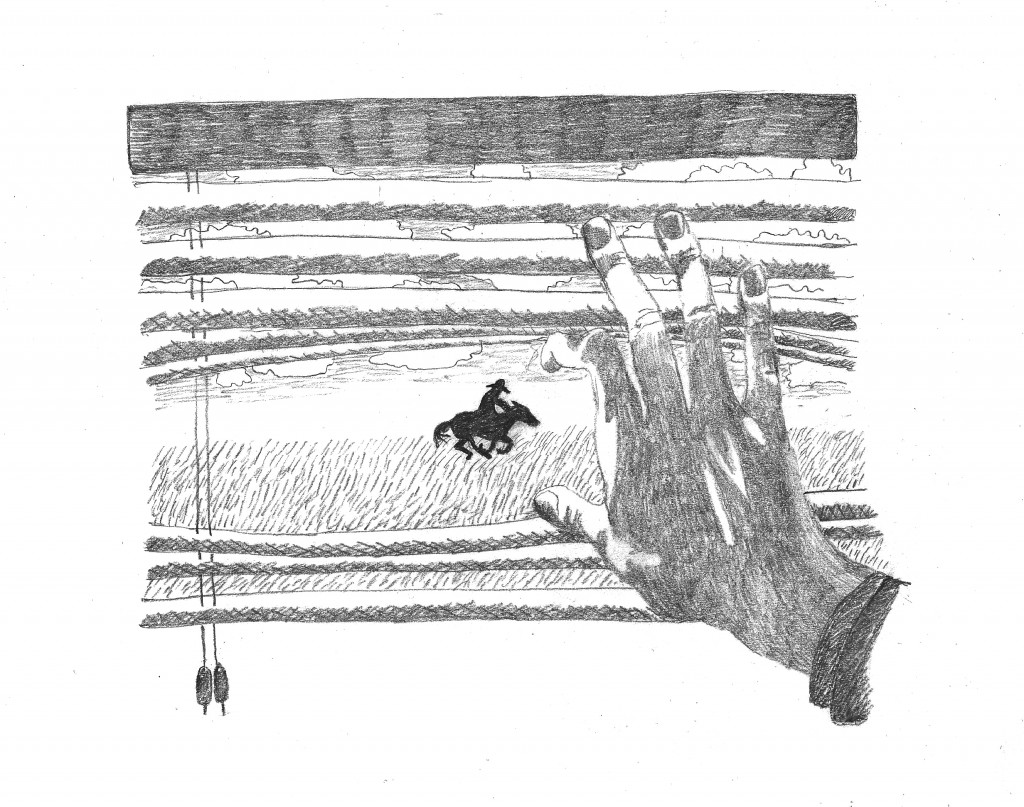

Illustration by Eliza Koch. See more of Eliza’s work here.

This post may contain affiliate links.