Howard Hardiman’s The Lengths — a gritty graphic novel set in London about a gay escort — cleverly begins like a screencap of Grindr. We see a catalog of bodies (with the burdensome possibility of appended personalities) accessible via touchscreen, with character breakdowns declaring age, height, build, “package” size, smoker/non-smoker status, drug use, and top vs. bottom preference. This is both Hardiman’s brilliant strategy for delineating characters from the beginning for the reader while likewise showing how the characters wish to delineate themselves — within a phantasmagoria of virtual tush — to prospective patrons of their parts.

The story centers around the frenetic, chronologically scrambled memories of Eddie AKA Ford “Escort,” the art-school-dropout turned male escort, described in his ads as “Ford: Cheeky Chappy. In/Out. Top. White Socks.” To trace the stages in this metamorphosis, the reader must piece together a personal narrative from these fragments. Through the course of The Lengths, we learn that, in art-school, Eddie was in a relationship with the politically active band-member James, and the two of them belonged to a gay-intellectual clique, along with the couple Krys and Dan. While at the gym (and still in art school), Eddie is approached by a photographer who asks him to pose for his Zine, Mincemeat, and with reluctance but piqued curiosity, Eddie agrees. This leads him into the arms/bed of Nelson, a physically and emotionally hardened escort. Venerating Nelson’s detachment and seduced by the teasing scraps of affection Nelson feeds him, Eddie is wooed into accompanying him on a gangbanging job. After, on leaving the elderly bangee’s hotel room, a fellow banger makes a quip about Eddie’s hotly frigid technique: “Did you really have to check Twitter while you were pissing on the client?” Eddie is thus exposed as something of a nasty natural, and so begins his new career, and the bifurcation herein of his personal and professional lives.

With a fervent nod to superhero comics, the beginning of Eddie’s double-life is marked by his purchase of a second phone. Now there’s a phone for Eddie and one for Ford, and soon, like a superhero, his body and its superlative functions become revered. Once he’s settled into his Ford identity, he gets back in contact with his art-school friend Dan and begins a tumultuous relationship with him, believing he’s keeping the Ford side of himself hidden. But for reasons of comfort both financial and identity-related, Eddie is reluctant to put Ford to rest, for he seems to relish the idea of belonging to everyone and no one, as opposed to just one. Exclusive intimacy would not only end his career, it would allow someone enough of his time to see beyond his form of crude self-portraiture. It makes sense, then, that the graphic novel’s version of a climactic “battle” scene is not between Eddie and an enemy, but between a drug-induced hallucination of multiple selves.

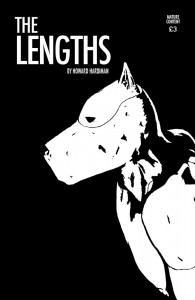

On top of the usual gay sexual subsets — top, bottom, twink, bear, otter, goose, etc. — used to facilitate balanced mating rituals, Hardiman deploys a strange and effective device in The Lengths for further classifying his men: he does so by breed. The author has chosen to bestialize his characters, designing them with alluring male bodies and hopefully less alluring dog heads. Said device simplifies the reading experience while complicating the book’s eroticism — jettisoning the possibility of readers’ arousal into the realm of the very uncomfortable as they thumb through the pages of tempting musculature and seductive shading that also seem the off-putting merger of Playgirl and Dog Fancy.

The characters’ “types” in The Lengths are thus immediately familiar through our basic preconceived notions of canine pedigree and the behavioral stereotypes ascribed to certain breeds. The sweet, unfit but intellectually engaged boyfriend character has a Terrier head. The chill, lanky, long-haired rocker ex-boyfriend has an Afghan head. The callous seducer and sex-work mentor — an HIV-positive sculpture of brawn and jizz — has a Doberman head. Our sought-after, corporeally commodified protagonist has a Great Dane head. The overlord of a seedy brothel has some sort of droopy-skinned Mastiff head. And of course there’s a cameo for a pseudo-intellectual museum-going Pug. Hardiman’s characters — illustrated as they are with thoroughly individuated, character-defining physiques — aesthetically adhere to old-fashioned comics’ sharp contrasting of sullen heroes, slimy overlords and shlubby sidekicks. For, in choosing to depict gay sex and sex-work via the graphic novel — a form that, despite decades of revolutionizing efforts at character nuance, will perhaps never truly rid itself of its archetype-heavy origins — Hardiman is able to mine our tendencies, especially within smaller communities and subcultures, of sociosexually typecasting ourselves.

Because it threatens to transgress these codes, it is in Eddie’s relationship with Dan that the primary theme of the story starts to show itself. Eddie mentions that he’s been with Dan for three months. “In a city full of temptation,” he says “You’ve got to measure the months in dog years.” Lauding himself for having made it three months in a relationship despite his smartphone’s vibratory siren songs of anonymous sex, we see the fissure between ideas of longevity and pleasure in contemporary gay discourse. Of course, this extends to orientation-nonspecific contemporary existence, but as this is an unequivocally gay novel, its commentary reads as culturally directed. Eddie continues, “When temptation’s only one click away, the arse always seems, um, greener? Heh, and when I’m the kind of temptation you pay to get in, so to speak, it gets a bit complicated.” But it’s not truly the lure of the savage terrain of uncharted buttholes that has Eddie so paralyzed — it’s the lure of not being seen, and thus not having to see himself, as something as unstructured as a full being. At another point, after a wholly blank, black page, Eddie rolls out of bed and says to himself, “Ever wake up and feel like your username is using you?”

Though the characters have confined themselves to the body bags of their typified physical appearances, and while Hardiman has, himself, imposed the connotations of breed upon their personalities, the author deftly resists two-dimensionality in his dialogue. The characters’ interactions are fluid, punctuated by stutters and pauses, neither canine, archetypal nor comic-bookish. Rife with cultural references (Hitchhiker’s Guide, Alexander Mcqueen, etc.), witticisms, abbreviations, moments of insufferable self-pitying cliché & melodrama, moments of earnest, and what, due to its foreignness, I can only assume is hyper-contemporary London vernacular, the characters interact pretty much like every young-ish human being I’ve encountered. When Eddie begins to get too self-absorbedly whiney, the author manages to undercut it with the protagonist’s self-deprecating goofiness, as in the aforementioned “climax,” where Eddie freaks out about his relationship while on Ketamine and imagines many versions of himself communicating with each other: “Why do you run away from anything that feels like okay?” “Oh, shut up. Is this meant to be allegorical?” “Your face is allegorical.” Bolstering his colloquial dialogue, Hardiman avoids the formality of speech-bubbles and captions, instead leaving text hovering and uncontained around the characters. Told in a series of memories, these moments of such concretely realistic speech are given a contrastingly insubstantial quality. With this textual realism depicted as floating and unfettered, the reader absorbs the book feeling the kind of overhanging melancholy one senses while watching a home video of a since-passed loved one.

Similarly, Hardiman forsakes narrative for whole pages to feature immense, expressive portraits of his mandogs in profile, set simply against a vastness of pitch-black. The tangentiality of the illustrations never seems overdone — it is just enough to assure us that this is no bodiced, neat or conclusive “story” about sex-work, but rather a well-researched immersion into a living environment that resists the finitude of a traditional narrative. His attention to detail within the illustrations is remarkable — on a second read, one picks up on hidden jokes, as in the newspaper sex-ads-page where Hardiman gives himself an ad-space as “Writer and Artist” next to the ad for a “Black Sex God,” or in an illustration of Eddie in bed, wearing immense dog-paw slippers on his human feet. Just as the book’s characters can exist within their structured sexual identities, and, when caught off-guard, reveal something far more interesting beneath, between the loose narrative, loose dialogue and the author’s detailed playfulness, we get a sense that this whole project is at once manipulating — while realizing that it’s happily ensconced in — its form. Brilliantly, Hardiman reserves his most poignant work for moments where the structure of the graphic novel has evaporated, when it’s not a graphic novel, but just space. Without the contrasting structure preceding it, though, space would bear no meaning.

With the privatization of gay sex as a result of the digitization of the gay public/meeting space, people have tapered their sexual identities down to the size of a smartphone screen, reducing themselves to the point that they do, indeed, mimic the two-dimensionality of old comic book characters. Just as people continue to enjoy the binary-heavy mythos of superhero stories for moralistic comfort, so too do we wish to fit into coded, predetermined sexualities to avoid confronting the blobby abysses of “authentic” selfhood and “authentic” desires. The Lengths is a gorgeous book that questions where such a large yet intangible thing as love fits into our shellacked and diminutive displays of our sexual “selves.”

This post may contain affiliate links.