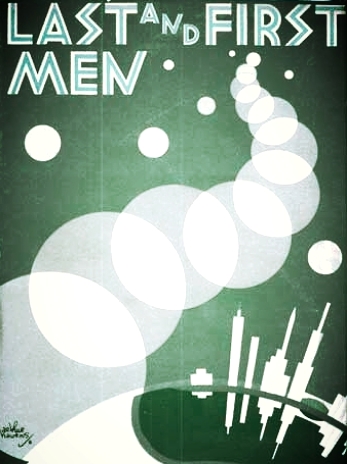

Last and First Men by Olaf Stapledon

I love reading Virginia Woolf because her books make me feel small, both childlike in wonder, and finite in scale. I get this feeling, for example, reading The Waves, when Bernard, in a moment of clarity, abstracted from his everyday egotism, reflects that “the earth is only a pebble flicked off accidentally from the face of the sun and that there is no life anywhere in the abysses of space.” What is this but an expression of the feeling people have as they, for a moment (although perhaps not since they were young), stare up into space on a particularly dark night?

Something of this element of Woolf’s fiction is encapsulated in Olaf Stapledon’s 1931 novel Last and First Men. But if these moments flash through books like The Waves, emerging only to be repressed again and again, in Last and First Men this sense of vertigo is stretched across an entire novel. Spanning 2 billion years, 3 planets, and 16 evolutionarily distinct human species, Last and First Men is a fascinating exercise in scale.

The premise of the book is that a human being from the far distant future has found a way to influence the minds of humans of the past and is writing to us through the novel’s ostensible author, Olaf Stapledon. His task is to share with us our future history, one which encompasses giant human brains in turrets, monkeys loaded down in gold lording over subhuman slaves, religions of motion and flight, Martians who communicate with one another telepathically via “wireless” messages and turn into blobs of jelly before swallowing groups of humans whole, civilizations under Venerian seas. Although Stapledon believes he is writing fiction, we are to stretch our primitive human minds to the utmost of our capacities and to imagine otherwise.

The ambivalent stance with which Stapledon wields the science fiction genre here irked many of his contemporaries. There is a rhetorical force of the dystopian science fiction novel that is lacking here. The author of a dystopia sets his story at an arbitrary point in the future, installs there a system of government, a set of class and gender relations, a technological milieu that reveals our present condition at a slant. Think Brave New World. Think Fahrenheit 451. Think 1984. It is difficult to read novels like these and not attend, if just for a moment, to their resounding critiques: if that is our future, we are doing something wrong, we must change. Perhaps it is due to their implied call to action that these books find their way into middle and high school curricula, a chance to stir apathetic students into life or political consciousness. Last and First Man is not free of dystopias, but by contrast they are nestled into a much vaster narrative, one whose Darwinian overtones call our efforts to build a just and beautiful world into question. What is the point of revolution when any outcome is reduced to the merest speck on the page of existence? What’s the point of struggle, toil, love? Humans, in Stapledon’s account will blow themselves to pieces, succumb to alien viruses, fling themselves into space, only to rise again and fall again and rise again and, like any species, ultimately fall.

By the end of the novel we are given two ways to look at this. Either our human existence, though in the vast scale of things a mere, tragic blip, is a work of art, a drama or a symphony that makes the cosmos more beautiful, or existence is meaningless:

Throughout all his existence man has been striving to hear the music of the spheres, and has seemed to himself once and again to catch some phrase of it, or even a hint of the whole form of it. Yet he can never be sure that he has truly heard it, nor even that there is any such perfect music at all to be heard. Inevitably so, for if it exists, it is not for him in his littleness.

This is a book to read when you want to feel small.

— Jesse Miller

“Millions of Americans Are Strange” by Nicholas Grider

Millions of Americans are writers. Millions of Americans write fuming comments beneath articles they’ve read online. Millions of Americans write profane and untrue things in bathroom stalls. Millions of Americans also write poems, novels, and short stories. Nicholas Grider — an American, like millions of other people — has written a short story called “Millions of Americans Are Strange.” By strange Nicholas Grider also means nervous, and perverted, and of delicate constitution, and underinsured, and working long hours, and living with cats, and asking a lot of near-strangers, and trying to connect the dots, and hyperventilating in parked cars, and capable of making moral judgments, and hesitant to venture outside, afraid they might vanish.

Millions of Americans have now read “Millions of Americans Are Strange.” Nicholas Grider has provided for millions of Americans a view of themselves from a vantage point millions of miles overhead, through a telescope with a focal-strength-ratio of millions to one. In this story millions of Americans recognize their own idiocy, their own fragility, their own embarrassment, their own functional alcoholism, their own Toyota Camry, their own furtive desperation, their own fundamental bewilderment. Millions of Americans now comprehend the extent to which they are distracted, ambivalent, craving clear instructions, doing the bare minimum, unable to wait any longer. Millions of Americans, upon reading Nicholas Grider’s excellent story “Millions of Americans Are Strange,” now see with perfect clarity how they are falling to pieces, and are keeping it together, and are maybe, probably, going to be fine.

— Meagan Day

The “before” scenes of infomercials

Is nothing easy? Some days I ask myself this question. When I have no clean underwear. When the train is thirteen minutes late. When I leave my phone behind in somebody’s car. When a pigeon poops on my head. Small difficulties, as they refract through larger difficulties (love trouble, family trouble, money trouble) are magnified to the point of becoming debilitating, like nasty little straws that, when they arrive at the right moment, can just about break a back.

At the discovery of a hole in my favorite sock, my pulse rises, hot energy collects behind my eyeballs. I think: Helen, you are not going to cry just because your big toe is more exposed than you would like it to be. But the thing is, maybe I will. Maybe I will cry because there’s a hole in my sock and no coffee left for breakfast. My holey sock arrives like a taunt from a school-yard bullies, plopping poop on my head just when things are starting to feel difficult in more substantial ways.

I have no health insurance and there is a hole in my sock.

But as it turns out, all it takes to brighten my cloudiest mood is the sight of, for example, a gigantic bowl of Cheetos tipping improbably off of a La-z-boy arm to be dispersed across a beige carpet, their neon orange powder settling heavily into the floor.

One of the greatest gifts the internet has ever given me is the isolation and compilation of the “before” scenes of infomercials, in which aspects of life at home — pouring Coca-Cola for your family, mixing chocolate cake batter — are depicted as impossibly difficult. Everything is breaking or broken. Coca-Cola spills across the prone laps of children, chocolate cake batter spurts into faces, opening the cupboard means fifty Tupperware containers raining down upon your head, the shoe won’t go on, the bread won’t be cut, my knees hurt, it’s raining on my barbecue, there’s egg on my hands, I have heartburn, I have flour on my face, there is TOO MUCH BAKING SODA IN MY MUFFIN.

With this avalanche of inconvenience, the tension in my chest eases, and I giggle happily at the absurdly staged travails of others. But what, precisely, is so effective about the seeing-someone-else-spill-Coca-Cola mood fix? What brings on that perfect “after” moment of my own, when I am grinning, a satisfied customer no longer concerned about the state of my socks?

This video is an enjoyable way to watch the infomercial clips I have been discussing:

However, the final scenes, in which unlikely gadgets handily resolve unlikely problems, ruin the cathartic effect. As I watch something brown spurt out of a badly-lidded container, my difficulties melt into a great sloshing sea of simple things gone horribly wrong. Together, me and my infomercial friend revel, spirits lifted, in the chaos. We don’t want new Tupperware. We just want to cry and laugh together over the crappy stuff we’ve got.

— Helen Stuhr-Rommereim

“The Father” by Tray Sager and “Pee on Water” by Rachel Glaser

I’ve been reading fiction. Mostly short stories. I liked Trey Sager’s story “The Father” published @ BOMB, and I also liked Rachel Glaser’s collection Pee on Water, especially the title story which you can read @ the website-which-shall-not-be-named, the one that rhymes with “Ice.” Some people have suggested that I write up a little something about why I liked these pieces. If you care enough to wonder why, please go read the piece! I can guarantee both of these pieces to be more interesting than my reasons why they are interesting, which I can almost guarantee will not be super interesting — something about history and feelings, reality and illusion, idk, life? Here goes . . .

“The Father” is more of a hip dad. The story cultivates adoration, so much so that I wound up projecting some major authority mojo onto its author, Sager, who lays down the kind of graceful conversational prose that sounds simply complex, all he said she said with the occasional line about the contraction of the uterus, I mean universe. Jesus, I thought while reading, I wonder if I will grow up to write like that. Structurally, The Father follows a man named Abe on his trips to and from the local sperm bank. So it’s just another story about semen. But it’s not like that. As suggested by many of this story’s proper nouns — names like Sarah and Abe (who together begat Isaac) — Sager tosses around some good old fashioned Old Testament fashion: marriage, procreation, God. Add in a trysting divorcee named Angie (or Angel if you’re not into the whole brevity thing) and several dillion nucleotide base pairs, and watch Abraham evolve from the guy willing to knife his son into the guy who claims his wife won’t let him have one. This Abe reincarnate is a flailing 21-century adult male who, in lieu of becoming a dad, visits the local Qi Gong clinic while neurotically mulling over his genetic stock: “He was half his father’s body, and he speculated there could be a time release in his DNA, contingent on the moment he transitioned from one parent into the other. Maybe there was a code inside him, an envelope mailed many years ago that had finally opened.” So the knife turned out to be a letter opener . . .

“Pee on Water” similarly concerns evolution cum ejaculation. Glaser laundry-lists the so-called development of the “wise man,” Homo sapiens. Cavemen “paint, cry, stare into fire meditatively. Pee on grass. Pee on dirt.” Yuppie dog walkers “pick up after their dogs. Shit in plastic. Shit in trash. Shit on grass. Pee on grass. Pee on pavement. Pee on pee.” “Snow falls all night, everyone wakes to good moods.” The entire story reads like a play-by-play sportscast of human history — a history that, much to my own delight, include sportscasts! “Harper dribbles the ball down the court, guarded by Ward, head fakes right, passes left to Pippen. Pippen up against Oakley, looks to see if Longley has posted, but Longley hasn’t posted, Longley is tangled with Ewing. Longley’s arms curl around Ewing while Longley’s little eyes look to lock with Steve Javie’s eyes, but Javie’s eyes follow the ball. Pippen drives by Oakley, then passes to Kerr who bounces it to Jordan. Jordan holds the ball, his eyes twinkle. He passes it back. Alone behind the three-point line, Kerr takes a breath, grimaces, shoots the ball into a spiraling three-point attempt, which hits the rim and sails out of bounds.” What a classic game!!! Glasser is like Marv Albert and basketball is life.

I also recommend Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, especially “Wintering Over” by James Brown and “Bettering Myself” by Ottessa Moshfegh, both of which can be found in the RR archive. I like this idea of Recommending a Recommendation. I hope we are able to send readers off down a never-ending chain of Recommendation. What would that feel like? I think it would feel very contemporary and also sort of like the plot of Alice and Wonderland.

— Peter Nowogrodzki

This post may contain affiliate links.