Midway through the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ secret show the power blows. Never mind the rented generators, or the truckload of extra staff. Dark are the stage, the twinkling string lights, the bulbs inside the shop. With the PA silenced, I can hear the sighing Pacific as the band strums on, and the audience sings. This starlit intimacy feels rare — although, actually, it’s not unlike any night at the Henry Miller Memorial Library, a cabin filled with books, art, and music in a redwood clearing in Big Sur. Which begs a question: if the Library is this magical sans megawatts, does it really need them?

By day, this 501(c)(3) non-profit is a bookshop, an archive for Henry Miller papers, and a rest stop for thousands traveling the sublime, coastal Highway One. It offers tea and coffee on donation, a lawn for sunbathing, and a resident feline to adore. It is also a hub for locals, an employer of three, and a place many more volunteer and live (among them, myself: the intern of summer 2011). “Where nothing happens” is the Library’s bumper-sticker motto — which would be untrue even if the Library were not also a venue for some of the biggest names in music. Which it is. In the last two years, the Arcade Fire, the Flaming Lips, and Animal Collective have walked its small platform stage.

It is these evening concerts, and the increased attention that has accompanied them, that elevate the question of the Library’s self-definition to urgent heights. How can the Library sustain its status as an exciting, relevant cultural institution, while remaining a refuge for the peace-seeking? Blown fuses are one thing; meeting Monterey County’s capacity bylaws, and pacifying picky neighbors, are another. At the place where everything and nothing happen, identity is a struggle, and always has been.

To wit: its namesake. Born 1891 in Brooklyn, Henry Miller is remembered for stream-of-consciousness, mostly autobiographical narratives — especially of his sexual debaucheries. He celebrated art, sex, and life: its excesses and explosions, its base and its bodily. His language matched his content:

I love everything that flows: rivers, sewers, lava, semen, blood, bile, words, sentences. I love the amniotic fluid when it spills out of the bag. I love the kidney with it’s painful gall-stones, it’s gravel and what-not; I love the urine that pours out scalding and the clap that runs endlessly; I love the words of hysterics and the sentences that flow on like dysentery and mirror all the sick images of the soul. (Tropic of Cancer, 1934)

This Miller the world knows best. Yet his move to Big Sur in 1944 (with third wife Janina Lepska and children in tow) changed him. Big Sur’s sublime beauty, isolation, and rugged lifestyle added spiritual depth to his worldview. In Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymous Bosch (1958), Miller writes:

The one difference between Big Sur and other “ideal” spots is that here you get it quick and get it hard. Get it between the eyes, so to say. The result is that you either come to grips with yourself or else turn tail and seek some other spot in which to nourish your illusions. Which leaves a whole universe to roam — and who is to care should you never come face to face with yourself? Only when we are truly alone does the fullness and richness of life reveal itself to us… The own precious self gets swallowed up in the ocean of being.

Coupled with his liberated sexual proclivities, Miller’s Zen-like philosophy generated a mystical, artistic aura over Big Sur. Particularly so in 1951, when a panicked article on rising West Coast countercultures appeared in Harper’s. “The New Cult of Sex and Anarchy” described Miller as heading a legion of anti-establishment, drugged-out, sex-crazed youth. The article was largely untrue, but became a self-fulfilling prophecy. After “The New Cult” was published, conscientious objectors, young literati, and occultists did, in fact, flock to Big Sur, seeking Miller and all that he symbolized. These were complicated expectations, since there was no cult, and since Big Sur’s rugged, remote locale challenges most that try to live there. Yet the young seekers came. “They think I’m the Dalai Lama,” Miller told a friend in 1951. “And I’m too weak to resist… Yet, despite its inconveniences, I’m attached to Big Sur. It’s my haven. And the sea, the wind, the cliffs, the sky, the stars are irreplaceable! I’ll never find a promontory like that in France.”

Miller was many things to many people, and ultimately, so was Big Sur. Inconvenience; haven; sex cult; natural paradise: the place was what you made it, or really, what you managed to hew from its steep cliffs and narrow highway. As Miller wrote, one has either to “come to grips” with its tough solitude, or “seek some other spot to nourish your illusions.”

Magnus Toren, director of the Henry Miller Library, arrived on a sailboat from Stockholm in 1984. He spent a decade wait-staffing posh restaurants, sailing, fishing, gardening, and living “a very good life” with wife Mary Lu on Partington Ridge (a pocket off the highway, where Miller himself dwelled). But after nearly a decade, the idea of spending his career in restaurants bothered him. In 1993, Toren happened to stop into the Library. After its establishment in 1981 by Miller’s close friend Emil White, the Library was then a dusty cabin, open only a few days a week, known to locals but not to visitors. The first director’s tenure was marked by legal troubles, and now its second was having trouble with the Big Sur Land Trust, the non-profit owner of the Library’s property. That second director told Toren he was quitting, and that the job was open. “I looked around,” Toren told me over a sandwich last July. “There wasn’t anything on the walls, or very many books. I said, what is this job?”

Toren applied, landed the position, and answered that question himself. He ordered more books. He involved himself in Miller academia, and made improvements to the Library’s store of Miller papers. He invited local artists, poets and musicians to show and perform. He hosted locals’ birthday parties. But he wanted the Library to be more than a sleepy bookshop open half the week. “It was like Henry was up there egging me on,” he said. “I felt like there was something we had to create.” He brought in more music, writing workshops, artists. In 2004, Miller fan Patti Smith agreed to do a fundraising concert, and from there the rest was history. Folk Yeah! Productions and Ian Brennan Presents had already been promoting indie shows at other local spots; they jumped on the opportunity to show their roster at such a spectacular location. The line-ups grew and grew. In 2008, Keely Richter came on board as the Library’s full-time archivist. Mike Scutari followed as Volunteer Manager a couple of years later. They, and Toren, do everything and anything that requires doing. And so did I in summer 2011, when the Library put on a total of 15 large-scale concerts, often more than one per week. The calendar that year included Blonde Redhead, Philip Glass, Ryan Adams, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

The Library can’t pay these acts their normal massive rates. But what true artist wouldn’t want to perform in a theatre of redwoods, with dedicated, generous staff running the show? In a recent issue of Sunset Magazine, Nicki Bluhm described it as “magical.” In 2011 Gillian Welch told SF Gate, “It’s kind of how things should be, where artists in different genres and different mediums all sort of coexist.” As a spectator you lie on the grass as the band sets up. You buy beers from the keg and leaf through old Henry Miller editions between acts. And then there’s the show, which is powerful not only musically but also humanistically. Instead of a stadium or a ballroom, with a high-crowned stage, rows of seats, and numbered tickets, audience and performer are contained by huge natural resources. It seems paradoxical, but skyscraping redwoods and endless stars make for an unusual feeling of intimacy. Many call it incomparable.

But while a squad of specialists arrive to help with the production of Folk Yeah! shows, the duty of preparing, staffing, and cleaning up the place after three hundred people file in and out falls on the Library’s three staffers (plus the odd intern or especially generous volunteer). It’s a strain. And while it’s hard to say what the community at large thinks of the shows, as so many live hidden away in the hills, there are complaints. After all, the bands are loud, and when hundreds of San Franciscans and Angelenos convene, the trim Highway One quickly clogs. “People think it’s subversive,” Toren said. “Like we’re being invaded by hipsters. I agree we can’t do [these concerts] all the time, but then again, I feel proud to introduce Big Sur to these folks. It’s great, I think.” He paused. “Sometimes I wish I could I bring those neighbors down to one of these fantastically amazing shows, and have them understand.”

Even more pressing is scrutiny from Monterey County with regards to health and safety requirements, including the Americans with Disabilities Act. There aren’t enough restrooms, and or potable water on tap. For a long time, the Library has been operating in a legal gray zone, and that the County has been generously vague about how many people are allowed to congregate. What is certain is that the Library is not currently zoned for serving visitors in the way it has been, and that the high numbers of past productions will have to come down. “We are working to create a place that is financially and otherwise sustainable by creating a legal carrying capacity of two hundred people,” Toren said. “We’re operating with a tacit approval from the county. It’s a little dangerous, in a sense.” Renovation plans have been filed, but if construction doesn’t begin soon, the Library may have to stop offering events. To avoid that danger, the Library must first meet its fundraising goal of $140,000. It is halfway there, thanks largely to grassroots supporters. But that’s just halfway.

Miller spent most of the 1950s in productive peace. But the wave of “cult-seekers” to Big Sur changed the paradisiacal quiet that had attracted Miller and many of Big Sur’s early artistic settlers. Indeed, Big Sur’s natural resources were also threatened, eventually leading to some of the strictest environmental development restrictions in the world. Due in part to the countless door-pounding visitors, and Miller’s eventual distaste for family routine, his marriage with Janina fell apart. With his next wife, Miller traveled between France and Big Sur a few times, in hopes of sparking fresh inspiration. But that marriage didn’t last either, and by the time Miller returned in the early sixties, the gorgeous isolation of Big Sur had changed — and largely because of him. His children had gone, and so had the life he’d known there. He left for good in 1963, having sealed Big Sur’s reputation as a countercultural haven. The Beats had already come; the Human Potential Movement would set up the Esalen Institute; the Tassajara Zen Center would find roots, too. Curious tourists never stopped coming.

So it is a complicated legacy that the Library shoulders. It serves at once as a hub for Big Sur locals (who, thanks to the environmental victories of the 1970s, enjoy near-perfectly preserved natural beauty and resources,), and as a relevant cultural center with international appeal. It is the place “where nothing happens,” while also celebrating a restless, complicated artist, whose zeal for life was perhaps his greatest message. Moreover, whether all locals like its or not, the Library represents Big Sur to a lot of people that visit. And that, in and of itself, is perhaps the toughest task of all.

Wisely, the Library has extended its profile outside of Big Sur with last May’s Big Sur-Brooklyn Bridge Festival. This was a five-day celebration of Miller and the Library, based out of Brooklyn’s The City Reliquary, featuring music, comedy, readings, a round-table discussion about Miller’s life, and a capstone performance by Philip Glass. A similar gathering is planned for Paris, centered at Shakespeare and Company. Brooklyn, Paris, and Big Sur: these were three major spots that marked Henry Miller’s long, ever-searching life.

But for the Library to be viable in its home locale, it may need to set some parameters for its identity. “I think we’re getting close,” Toren said. “I’d like to profile the library, in the future, as the place where you actually meet the artist. That [the Arcade Fire’s] Winn, for example, would offer himself up, kind of naked, with his guitar. What the first song he learned was. His process. What made it so important for him to write music.” Toren’s laptop blinks; it is an email from a director he is about to feature at a Library screening that night. “We could have people from the film industry, too. It could be like a salon, with slides, and lectures.” That intimacy is already the best part about those big-name shows, and it may be closest to the Library’s truest, most sustainable self — along with the bookshop, archive, and Norwegian Forest Cat. A “meet-the-artist” series would be the very best of all those worlds the Library straddles.

The Library has a long way to go towards that very best identity — $70,000, to be exact. But as one of the world’s most magical arts organizations, in one of the world’s most magical settings, it’s essential that it get there. Miller wrote, “Who is to care should you never come face to face with yourself?” In the case of the Library, lovers of nothingness — and something-ness — all the world over.

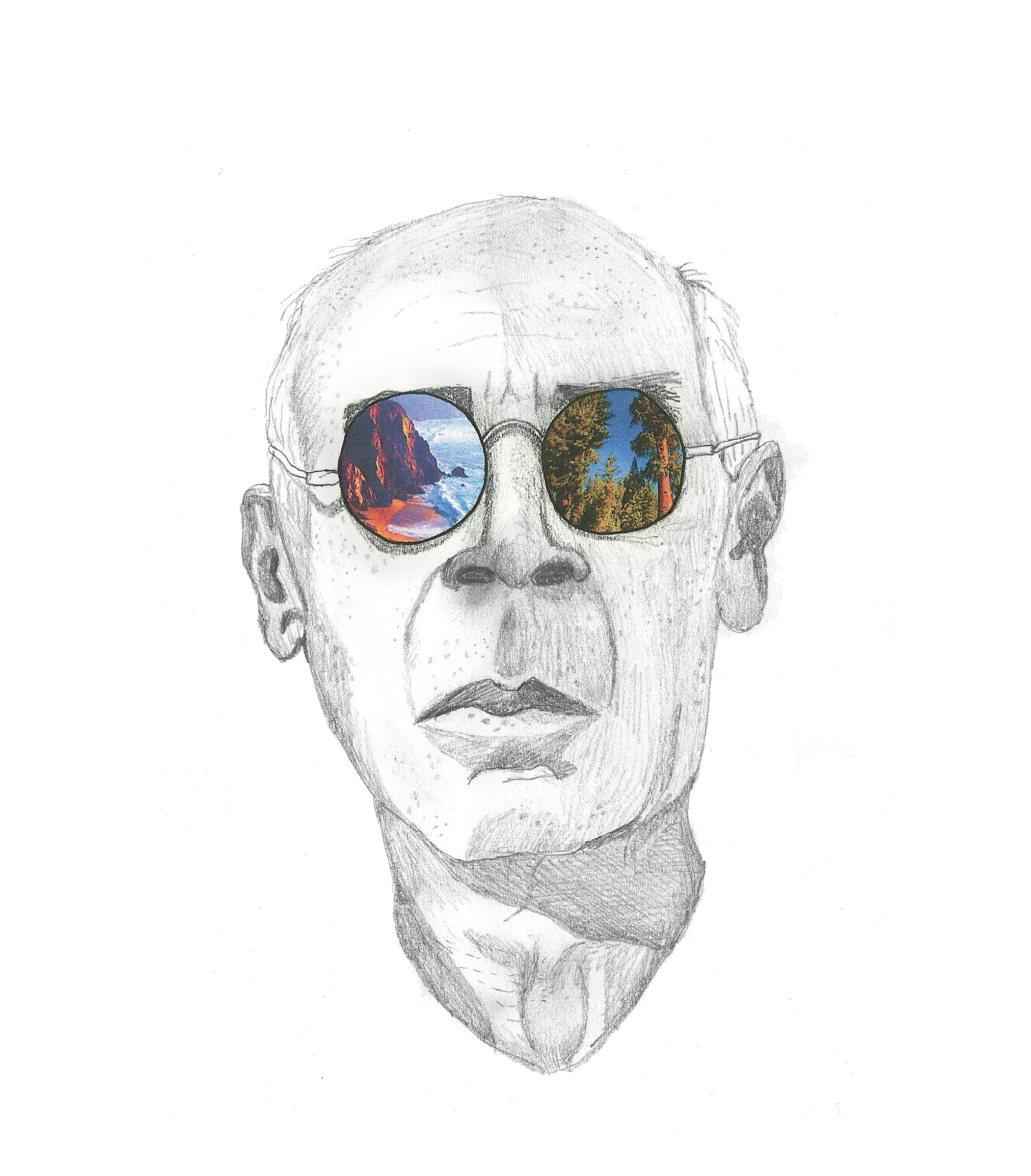

Illustration by Eliza Koch. See more of Eliza’s work here.

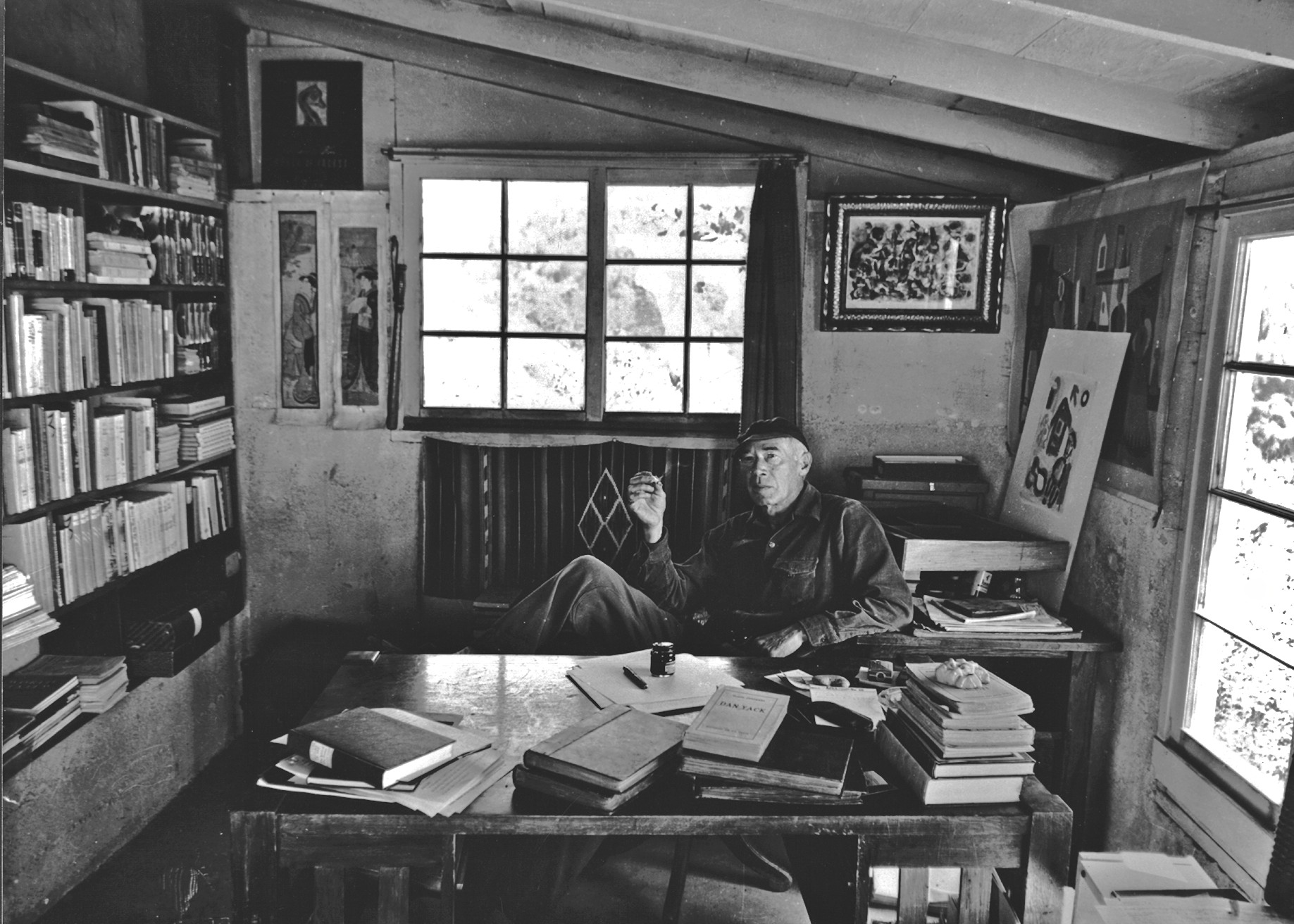

Photographs from the Henry Miller Memorial Library’s website.

This post may contain affiliate links.