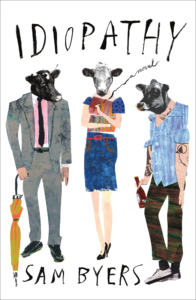

Idiopathy, the debut of British novelist Sam Byers, is a pitch-perfect contemporary take on the social novel, somewhere in the vicinity of Evelyn Waugh or Jonathan Franzen. Awake to both the subtly human and bitterly hysterical faces of contemporary life, it chronicles the self-destruction and insecurity of three young adults trying to justify their existence. That it does so with class and wit is testament to Byers’ ability to empathize with the struggle, and desire to demonstrate how it inevitably evolves into a life.

Nathan returns home after months in a rehab facility to find the world as tryingly absurd as it was when he abandoned it. His mother has spun their family’s difficulties into “Mother Courage,” an online personality with attendant book deal and various media appearances. He must face the remnants of his former life, including the people he abandoned when he disappeared during the party he simply refers to as “That Night.” Among these remnants, for reasons that reveal themselves as the book progresses, is Katherine.

Katherine is spinning her wheels: stuck in a debilitating job running fire drills as a Facilities Manager, bulimic and cigarette-addicted, and, despite her best efforts while watching the evening news, apathetic in the face of world hunger and children’s suffering. Although anyone who bothers to look can see that her vacuous lifestyle is taking its toll, she still thinks she’s pretty much got it figured out.

Some [of her colleagues] wanted to fuck her because they liked her, and some of them wanted to fuck her because they hated her. This suited Katherine reasonably well. Sometimes she fucked men because she felt good about herself, and sometimes she fucked them because she hated herself. The trick was to find the right man for the moment, because fucking a man who hated you during a rare moment of quite liking yourself was counter-productive, and fucking a man who was sort of in love with you at the peak of your self-hatred was nauseating.

And this works for her for a number of months, until she gets pregnant by Keith: a buffoonish coworker who, long a womanizer, has begun treatment for sex addiction, and wears a rubber band on his wrist that he snaps to purge his mind of impure thoughts.

Daniel (Katherine’s ex and Nathan’s friend) is a Public Relations man for a GMO-Corn company. Though secure at work, he fears his home life is hollow, ever increasingly with each half-sincere declaration of love to his girlfriend Angelica. Between the strain of Angelica needling him over his “Dan-flu” (which is to say, more the idea of a flu than any actual ailment), and the wedge driven between them by her obnoxious, dim-wittedly liberal friends, Daniel’s calm persona is starting to fray around the edges. When describing these friends, Byers gets the opportunity to showcase his knack for social comedy. For example, at an early dinner party:

The most common visitors were Sebastian and Plum, who were visiting this particular evening. Plum was Plum’s given name. She had those kind of parents. Her sister was called Nasturtium. Sebastian, rather ironically, was not Sebastian’s given name at all but simply a name he happened to prefer to what he’d actually been christened: Walter. Sebastian, much to his chagrin, had those kind of parents.

…

“I mean,” said Sebastian, “just look at Afhanistan.”

“Oh, I know,” said Angelica. “Afyanistan is a horror. To think that man actually took us there.”

It was, Daniel noticed, an unspoken agreement within the group that the names of foreign countries had to be pronounced with a slightly different inflection than was usual, delivered with such confidence that it implied ignorance on the part of anyone oafish and colonialist enough to say Afghanistan.

“You know,” said Sebastian, leaning forward in the manner that always presaged his saying something intense. “The Native Americans have this really fascinating approach to the whole concept of leadership.”

“Oh I love their outlook on things,” said Angelica. “Like their system of non-ownership and their whole attitude to the land? It’s so awful that we just crush these cultures without learning from them first.”

“It’s true,” said Daniel. “We should learn then crush.”

Daniel seems to be the unheeded voice of sanity during these antics, but is too willing to just go on with appearances and dissociate from his surroundings. Although this passivity enables him to maintain his hollow relationships, it is in fact the source of his troubles.

Idiopathy’s three protagonists are stuck in their own heads, subject to a narcissistic self-criticism that betrays a deep-seated need to be loved. And they go through similar journeys from anxiety to acceptance as the book makes its way to resolution. Each protagonist’s crisis is centered around their relationship with another character, and resolution comes for each when they come to terms with that relationship. With Keith, Katherine grapples with her body image, pregnancy, and the choices she’s made about it; with Angelica, Daniel confronts the honesty and genuineness of his own emotions, and the widening gap between a life imagined and a life lived; in isolation with himself — the Self, even — Nathan, in isolation, struggles with the potential impossibility of connection with other beings. They are constantly at cross-purposes, constantly talking and thinking around each other: believing that they know precisely what the other does and will think, feel, or do. But more often than not, they get it comically backwards. All comes to a head in a virtuosic set piece, when the three friends get together for a night. It is to Beyers’ credit that he does not forsake his characters, that in their flaws might lurk their redemption.

And redemption is the right word. The book’s moral center, Nathan is a somewhat messianic figure. His silence and sensitivity belies the violence implied by his physical bulk, tattoos, and scars. Near the end of the book, he offers a memory from childhood:

He remembered, he said, cutting his finger when he was a kid, and staring at it, watching the blood bead up along the edge of his knuckle, and feeling nothing, and being unbelievably excited by the thought that he didn’t feel pain anymore, that perhaps he’d grown out of it, and running to his dad and holding up his finger and telling him it didn’t even hurt, and his dad saying it was because the air hadn’t gotten to it yet, and then right as his father said that he could feel the air get to it and his finger started hurting and he started to cry.

It is this sort of empathic depth that so startles about Byers’ writing. His characters lead the lives they do because they could be no other way. It remains surprising how carefully constructed his characters are, how purposefully choreographed their actions and thoughts have been. None of the characters really gets what they thought they wanted, but they do get the wisdom to best appreciate where they have ended up. Ultimately, it comes down to Byers’ devotion to his readers. He wants to bring them, against their will or knowledge, along with these people. He wants that when these characters are changed, so are we.

This post may contain affiliate links.