Thomas Hirschhorn’s newest monument, built in honor of the Italian Marxist theorist, Antonio Gramsci, has the feel of a plywood playground. The maculate installation and community space, built in the courtyard of a public housing project, at first appears appropriately undisciplined in its celebration of Gramsci’s legacy. Consequently the monument, for better or for worse, overtakes the space and bleeds into the surrounding community. In the Forest Houses in the Bronx, banners displaying Gramscian aphorisms such as “everyone is an intellectual” are everywhere. The space first appears as an explosion of romantic idealism, staged in a working class community of color that, like most in this country, when not blamed for the prevalence of drugs, crime etc, is simply ignored by the mainstream.

Thomas Hirschhorn’s newest monument, built in honor of the Italian Marxist theorist, Antonio Gramsci, has the feel of a plywood playground. The maculate installation and community space, built in the courtyard of a public housing project, at first appears appropriately undisciplined in its celebration of Gramsci’s legacy. Consequently the monument, for better or for worse, overtakes the space and bleeds into the surrounding community. In the Forest Houses in the Bronx, banners displaying Gramscian aphorisms such as “everyone is an intellectual” are everywhere. The space first appears as an explosion of romantic idealism, staged in a working class community of color that, like most in this country, when not blamed for the prevalence of drugs, crime etc, is simply ignored by the mainstream.

The conceit and challenge of the piece is two-tiered. It attempts to bring Gramsci’s ideas to a larger audience, while creating a space that will challenge and transform the means by which such knowledge is produced, valorized, and disseminated. The Marxist outlook, from which Gramsci’s ideas stem, recognizes that one’s relationship to capitalist structures determines consciousness, a consciousness that necessarily contradicts, and then can either attempt to negate or obfuscate the reality of one’s relationship to those same capitalist structures. Idealistic philosophy is perhaps the most prime and unfortunate example of how a desire to change the existing world around you is ironically determined by, and tends to alienate you from, your privileged relationship to the status quo (anybody who has been lucky enough to go to college or grad school is no doubt familiar with this fact). This contradiction lies behind the long existing stereotype that Marx (or critical philosophy in general) is a phase you go through while a student, a phase that ends as soon as you leave the collegiate bubble and enter the “real world.” Gramsci, aware of this contradiction, understood and imagined education to be not an undeniable privilege of the ruling class, but a site of class struggle, where the reality of classed society could transform and be transformed by the pursuit for the ideal of universal intellectualism, and political consciousness detached from class privilege.

Hirschhorn’s piece pays homage to and attempts to emulate this novel sentiment. Initially, the attempt of one successful European artist to swoop in and open up the contradictions between radical philosophy and the division of mental and physical labor that continues to police the borders of race, class, and caste in this country struck me as arrogant and patronizing. Still, I’m cautious to condemn Hirschhorn for having the audacity to try, and I wonder whether or not it is misguided to hope that the installation might actually achieve something both radical and reparative.

But while questions that focus on Hirschhorn and his personal stake in the project are no doubt integral to any analysis of the monument, these questions should not overshadow the consideration of how local residents themselves (and working class people of color more generally) relate to the installation. This means lending agency to those residents who helped build and who utilize the space, and requires that critics do not simply reduce questions about the project to the motives of one privileged (white) artist. But so far I have found only one review that includes interviews with residents of the forest houses — which I would suggest taking a look at, although it is certainly not an authority on the matter.

That this project was orchestrated by a well-established artist from Switzerland, staffed by local residents, and funded by an elite contemporary art organization is good reason to be cynical. I feared the piece would implicitly glorify the artist as a benevolent white savior, bringing cultural and political enlightenment — not to mention jobs —- to a community often imagined as barren and lacking the capacity to help itself. The fantasy that cultural and political engagement is a gift bestowed upon the poor by often white and rich benefactors is characteristic of the all-consuming culture of gentrification, and the prevalent ideology of supply-side economics.

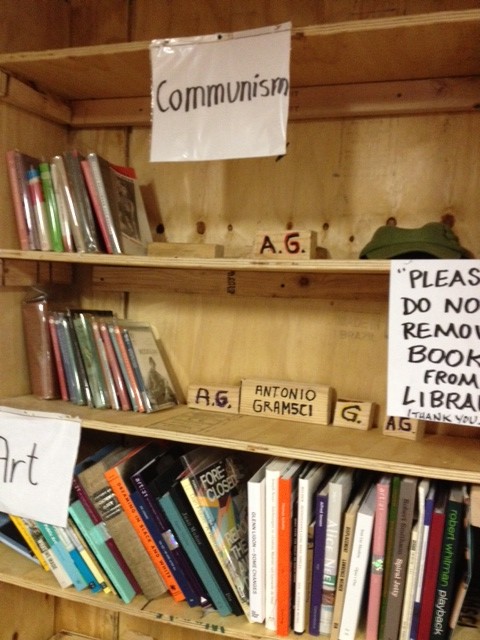

That being said, when I actually visited the monument, I found what appeared to be intentional and considerate community space. The monument is impressive insofar as it provides a variety of community services without imposing a dogmatic or programmatic vision of how to appropriately use them. There is a local newspaper and radio station, which combines a discussion of Gramsci’s legacy with community news. There is a small library containing the work of Gramsci and his contemporaries. There are daily art classes, and a small classroom stocked with computers. There’s a bar around the corner from a modest lecture space where German philosopher Marcus Steinman gives daily lectures on whatever he or the audience feels like talking about.

The monument left me feeling hopeful, but it was a hope tempered by ambivalence — ambivalence about the project itself but also about my presence in the Forest Houses. But, as I lingered in the space, I became less focused on what my presence there meant and more interested in how others were engaged, which was a relief. I was suffering from a kind of tunnel vision, the kind you get when too obsessed with the stakes of your own judgment, and a kind best solved by engaging in projects that are much larger than yourself.

Some of the more critical reviews of the monument dismiss the piece offhand for being a specious and narcissistic attempt at radical community art. But such a position rests on the same fantasy of white saviorhood that led me to be apprehensive about the monument to begin with. Ken Johnson, of the New York Times laments:

“As it was, it all made me sad: I had a vision of the great man descending upon the benighted residents of Forest Houses to spread his manna and impregnate the community with an embryo of hope, but one that was doomed to fade after the construction is dismantled at the end of the summer”.

In his review, Johnson implies that the space fails to bring hope because it is made out of cheap material, that it fails to bring permanent jobs because it is only temporary, and that it fails to actually teach anything useful or meaningful to the residents of the Forest Houses because there are too many non-intellectual distractions. It is true that the temporariness of the structure (it will be taken down during the week of Sept 16th), begs the question of its usefulness. However, Johnson’s dismissal betrays an elitist understanding of education and community activism — one which too readily embraces the idea that contemplation and work, like meaningfulness and usefulness, are mutually exclusive. The Gramsci monument tries to close this rift by challenging the assumption that a space between can either be useful for those who need it, or meaningful for those who don’t, and that these spaces should not be separate. The idea is that one learns about Gramsci through experience as well as theoretical discussion, and in the process one challenges outdated associations of contemplation as bourgeois, and work or labor as proletarian.

The image of socialism imagined within the radical model of education offered by Gramsci and honored by Hirschhorn’s monument is harshly juxtaposed against the reality it both responds to and wishes to negate. And whether or not this then problematically obfuscates differences of race and class privilege is hard to say. Think of it this way, in one sense white and wealthy folk are invited to challenge the ownership of intellectual resources by the privileged, while in another sense they are invited to, for one summer, gentrify a working class community of color, no doubt feeling a little uncomfortable or even guilty, but more than likely proud of themselves for coming at all. For many this aspect of the project elicits cynicism. While I agree, I am wary of the kind of cynicism that can lead one to be defeatist and phobic. When I attended one of professor Steinman’s lectures, it was the self-identified residents of the Forest Houses who were most vocal in the space, a fact that I would not have known if I had dismissed the project entirely. If awareness and consciousness of one’s race or class privilege becomes a reason to fear or avoid communities of color where markers of privilege are most apparent, then isn’t that missing the point of such awareness?

Still this does not excuse the narcissism of the savior complex, which seems to haunt any attempt to challenge racial or class difference from a position of privilege, and which, more often than not, effaces the reality it wishes to challenge or negate. That is why I am sympathetic when Ken Johnson concludes that Hirschhorn’s piece is primarily a “monument” to his “monumental ego”. This, however, is an overly simplistic critique, one which demonstrates the tendency to reduce the judgment of the monument to an assessment of Hirschhorn’s ego, as well as the tendency to dismiss the experience of those residents of the project houses that have felt empowered by sculpture.

This post may contain affiliate links.