“We are not in search of death; we are looking for real life.”

— Tiananmen Square Hunger Strike Declaration, 1989

In an eight by ten foot cell in California, Todd Ashker is starving. He hasn’t eaten in nearly six weeks, and his body has begun to lose muscle mass. Exhaustion has set in, and his organ functions have slowed. In the windowless cells on either side of his, more men steadily starve. These men are isolated in the Secure Housing Unit (SHU) of California’s Pelican Bay Prison, a tidy euphemism for long-term solitary confinement. Pelican Bay is the state’s most notorious supermax prison, reserved for what officials identify as “the worst of the worst” criminal offenders.

In this space, California’s “worst” are engaging in one of the most radically nonviolent acts of resistance a protestor can employ. They have elected to starve themselves until the state agrees to meet their five core demands – chief among which is a call to end the well-worn practice of indefinite solitary confinement. To achieve a life behind bars that resembles one worth living, they are risking death. After repeated attempts to negotiate with the California Department of Corrections to improve the conditions of their confinement (as well as two previous hunger strikes), these men have turned to the only tool they have left, offering their bodies in a dramatic act of corporal dissent.

In spite of their extreme isolation, the stark SHU cells at Pelican Bay are the unlikely birthplace of the California prisoners’ hunger strike, which spread to two-thirds of the facilities across the state, engaging 30,000 prisoners at its peak. Prisoners held here are the most dramatically exiled segment of an already banished population; the most aggressively marginalized people confined in the state’s massive and dysfunctional correctional system. More than 500 prisoners at Pelican Bay have survived in solitary confinement for more than a decade.

Historically, politically motivated hunger strikes have been employed by the free and the imprisoned alike; from Irish prisoners to Chinese students, to imprisoned activists and tomato harvesters, to suffragettes and journalists. While for obvious reasons self-starvation is generally considered a desperate last resort, the strategy has been most notably utilized en masse by prisoners, who lack the mobility and power to engage in other modes of protest.

Bobby Sands, an Irish nationalist who lead the 1981 Irish prisoners’ hunger strike, sought to reclassify thousands of people as political rather than criminal prisoners, thereby demanding reforms to their conditions of confinement. He was so successful as a leader and gained so much media attention during the strike that he was elected a member of Parliament. Though the hunger strike ultimately lead to his death, his election galvanized public support for the prisoners’ cause, leading to the election of numerous nationalist party members. In today’s world of mass incarceration as the accepted American standard, it is a challenge to imagine a parallel political success story for prisoners in California.

While advocates throughout the state and across the country have demonstrated in solidarity with the hunger strikers, California prisons chief Jeffrey Beard only begrudgingly agreed to meet advocates on behalf of the prisoners after weeks of protest in early August, while his office made clear that this meeting should not be misinterpreted as “a mediation or negotiation.” Shortly after, he wrote an inflammatory editorial for the LA Times, dismissing the hunger strike as “gang power play,” and needlessly highlighting the violent backgrounds of the incarcerated strikers. According to Beard’s disjointed logic, an individual’s violent past is enough to warrant the inhumane conditions that the United Nations has likened to torture.

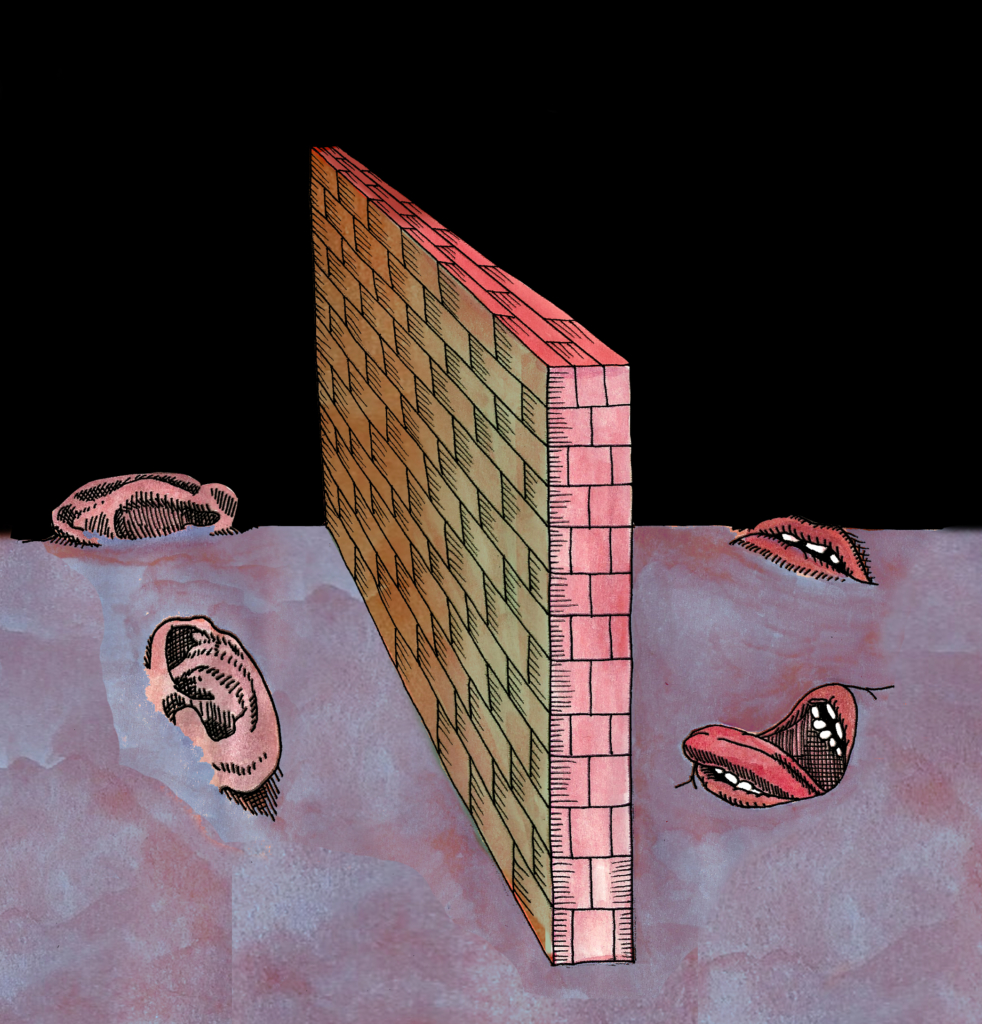

With more than 300 remaining hunger strikers closing out their sixth week of refusing food, a question uncomfortably lingers: is anyone really listening? A recent LA Times editorial cartoon bluntly and accurately notes that a hunger strike can only succeed if the society whose attention it seeks to engage has a conscience. A fleeting mention in an article or a social media share is a start, but these passive actions alone have clearly not inspired enough support behind the prisoners in California to motivate large-scale change on the part of the CADC. As their situation grows more perilous by the hour, the question of American conscience, or lack thereof, rings louder than ever.

Illustration by Eliza Koch. See more of Eliza’s work here.

This post may contain affiliate links.