Last year, I received a phone call from a mortified friend, bemoaning the fact that she had just done something truly awful and embarrassing in front of a colleague.

Last year, I received a phone call from a mortified friend, bemoaning the fact that she had just done something truly awful and embarrassing in front of a colleague.

“Awful and embarrassing?” I asked, skeptically. “What the hell did you do, write a piece of fan fiction?”

I know it’s a bit cruel, but I’ve always been rather sniffy about the phenomenon of fan fiction. I suppose that’s not really fair, given my limited experiences with it, but as Ewan Morrison said in a 2012 article for The Guardian on fanfic origins, it’s a medium typically “seen as the lowest point we’ve reached in the history of culture — it’s crass, sycophantic, celebrity-obsessed, naive, badly written, derivative, consumerist, unoriginal — [even] anti-original.”

Until lately, this observation generally summed up my feelings on the subject. Nobody over the age of 10, I thought, ought to be appropriating popular characters for their own stories. Even in light of Kindle Worlds, Amazon’s shiny new fan fiction publishing platform, I still scrunched my face up in disdain at the idea of people writing erotic thrillers about Spock, Harry Potter, and characters from Twilight.

The idea that cinema — truly great cinema, at that — could be regarded as fan fiction was certainly not one I had ever considered. After all, by the virtue of being a collaborative art form, film lacks the self-indulgent immediacy afforded by writing or drawing. It’s much simpler for the average fan to pen a story than it is for them to produce a movie (and that’s not even to mention the aspect of fair use and licensing).

However, my view on the matter was recently challenged by a statement from popular culture expert Francesca Coppa in a piece for the PBS web series Off Book (episode 15: ‘Can Fan Culture Change Society?). She argues:

“Fandom is saying: ‘I really like a much more active participation with my culture.’ [You] don’t just see a movie and walk away from it; [you] want to discuss it afterwards, [you] want to write stories about it.”

I found myself surprised by Coppa’s comment — or more accurately, surprised by my reaction to it — because the first thing that popped into my head upon hearing it was not something decidedly geektastic like Star Trek or Doctor Who, but rather, the French New Wave.

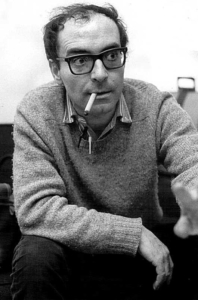

After ruminating on this unexpected association for a bit, I came to a most alarming conclusion: Jean-Luc Godard wrote fan fiction.

Now, the fanboy origins of the French New Wave auteurs are well–documented. Disenchanted with the staid, theatrical “Tradition of Quality” films being produced in postwar France, cinéphiles like Godard and François Truffaut turned their attentions to the pulp thrillers and cowboy Westerns coming out of Hollywood. Their obsessions with directors such as John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, and Howard Hawks, prompted them to engage with film professionally, first by writing criticism for André Bazin’s Cahiers du cinéma, and then ultimately, by making movies themselves.

Even after becoming established filmmakers, the New Wave directors remained deeply entrenched in fan culture, blending their own styles with homages to their idols. From the famous “Bogie” scene in Breathless, to the Chabrol’s James Dean-esque protagonist in Le Beau Serge, Paris was never too far removed from the imprint of Hollywood. In the magnificent Hitchcock/Truffaut (a published transcript of the latter’s marathon interview session with the Master of Suspense), Truffaut confesses to Hitch that he still routinely attends cinémathéque screening of The Lady Vanishes (sometimes twice a week), gushing: “since I know it by heart, I tell myself each time that I’m going to ignore the plot…to study the camera movements…but each time, I become so absorbed by the characters and the story that I’ve yet to figure out the mechanics of that film.” In other words, Truffaut considered himself to be a film buff first, and a director second.

Even after becoming established filmmakers, the New Wave directors remained deeply entrenched in fan culture, blending their own styles with homages to their idols. From the famous “Bogie” scene in Breathless, to the Chabrol’s James Dean-esque protagonist in Le Beau Serge, Paris was never too far removed from the imprint of Hollywood. In the magnificent Hitchcock/Truffaut (a published transcript of the latter’s marathon interview session with the Master of Suspense), Truffaut confesses to Hitch that he still routinely attends cinémathéque screening of The Lady Vanishes (sometimes twice a week), gushing: “since I know it by heart, I tell myself each time that I’m going to ignore the plot…to study the camera movements…but each time, I become so absorbed by the characters and the story that I’ve yet to figure out the mechanics of that film.” In other words, Truffaut considered himself to be a film buff first, and a director second.

Of course, it’s probably a stretch to claim that appropriation of genre alone is enough to define an entire oeuvre as fanfiction, but even if we dismiss that notion outright, it still leaves us to ponder the interesting case of Godard’s Alphaville.

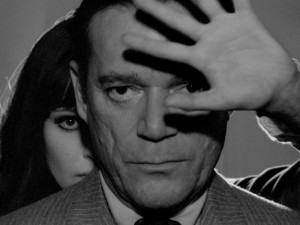

The full title of this 1965 dystopian, sci-fi thriller is Alphaville: Une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution (A Strange Adventure of Lemmy Caution). This is important to note, because unlike Godard’s other protagonists, Lemmy Caution was not a character of the director’s own creation. He was, in fact, the American hero from a series of detective novels by British writer Peter Cheyney — largely overlooked in Britain and the United States, but wholeheartedly embraced by the French. Between 1952-1963, at least seven Lemmy Caution films were produced in France, nearly all of them featuring Hollywood reject Eddie Constantine (who reprises the role in Alphaville). These movies depicted Caution as a hardboiled Dick Tracy type, and followed the classic B-movie formula of guns, girls, and more guns.

In Alphaville, however, Caution finds himself in a completely different milieu, lost in a futuristic technocracy ruled by a dictatorial computer. This radical shift—an abrupt change in setting orchestrated purely to suit Godard’s own fanboy reimagining of a beloved character—is the very essence of fan fiction as Coppa describes it. Alphaville is Godard’s active engagement with popular culture; his way of expressing political and social values within a familiar context.

Moreover, Godard actually endorsed the practice of fan-driven subversion. In his book on Alphaville, author Chris Darke draws attention to a 1958 review Godard wrote about a Jean Rouch film called Moi, un noir, in which the a group of African youths take on the personas of popular figures. “[Godard] observed with delight,” Darke writes, “how…Lemmy Caution was revealed as a character available to be lifted and interpreted by others.” Granted, Godard’s interpretation effectively put an end to the character’s life onscreen (not well received outside of the arthouse crowd, Alphaville all but destroyed Constantine’s popularity in France), but it still stands that he was on board with the fandom philosophy.

It’s unlikely that I’ll ever read Fifty Shades of Grey or develop a fondness for My Little Pony/X-Men crossover art, but I think I’ll be a little bit kinder to fan fiction from now on. After all, if it’s all right for Godard, Tout va bien, non?

This post may contain affiliate links.