All personal and social histories are informed by differing understandings of time and life cycle. In secular western communities, for example, we tend to speak about our lives as beginning on one specific date (our birthday) and ending on another: the day our bodies finally “give up the ghost.” But in other cultures, an individual’s story may begin with a creation myth or the birth of their grandparents. It may begin the moment they were first conceived of by their mothers, not in their wombs but in their minds, and end seven generations after theirs — or not at all.

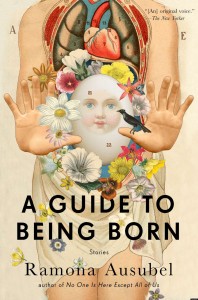

Each section of A Guide to Being Born, by Ramona Ausubel is comprised of stories related to birth, gestation, conception, or love, though the phases of life to which each section refers cannot be neatly plotted on a timeline. In the opening story, “Safe Passage,” a shipload of grandmothers finds themselves drifting aimlessly across calm, infinite waters. Are they dead, or being reborn? They are grandmothers, but are they old? This may be a disconcerting place to begin a collection about the transformative moments in life and reproduction, but perhaps that’s also what makes it the most appropriate of beginnings.

While each story refers to universally recognizable stages of development — pregnancy, first love, loss, and aging — none make use of the obvious perspective. In “Chest of Drawers,” notions of pregnancy and parenthood are explored through the narrative of a man whose chest grows drawers of bone that protrude as stubbornly as his wife’s growing belly; hers bursting with life and his waiting to be filled; “Poppyseed” is told from the alternating voices of a couple who make the difficult decision to halt the onset of puberty in their developmentally disabled daughter while nurturing a determination that some part of her still might grow; and “Tributaries” conjures a world in which a person’s love is made visible — or, sadly, isn’t — by the growth of a new limb for each outpouring of new feeling.

Ausubel succeeds at both thrilling and nauseating, knitting together the wondrous and the grotesque. In the same way that work by writers like Karen Russell combine the monstrous and mundane, Ausubel imbues the physical with fantasy. Her characters feel every detail of their bodies as they become toned, loose, or otherwise departed, yet the everyday experiences of blood, skin, muscles, hair, and teeth are exaggerated or offset by the imposition of something surreal: the insistence that one’s baby is a changeling species, or the awareness that one is not alive, yet “is.” Suitably, Ausubel’s prose is as playful yet controlled as her imagination. In “Savers,” newly acquainted lovers imagine that they are a pair of saguaro cacti:

Our arms are wrapped around each other’s necks. It is warm out and we are growing bright pink flowers. Our spines prick one another’s four-hundred-year-old skin and the water inside us seeps out in little beads. . . . The small birds that make homes in our bodies have left us alone in the dark.

Read alone, the less outrageous stories to be found in this facetiously titled “guide” could be said to contain nothing otherworldly at all. The young couple in “The Ages” measure their own life trajectories against those of the elders in their neatly ordered neighborhood, and the boy in “Welcome to Your Life and Congratulations” deals with death for the first time after his cat is hit by a car. These stories are not out of place, though; indeed, their inclusion is what makes the collection as a whole so alluring, so uncomfortable. These are fleshy fictions rooted in reality, miraculous bodies that produce and become disused like every other. With this collection, Ausubel proves her talent for capturing the curiosities of life in all its messy, strange, and ordinary glory, reflecting whole imagined universes within and around us all. Best of all, the reader is welcome to order them in any way she likes.

This post may contain affiliate links.