By my mother’s memory, my grandfather didn’t start writing poetry until after they came to the United States, just after the fall of Saigon. So his is the verse of expatriates: formal, eight-line poems haunted by dark nights, fluttering snow, and gold leaves shimmering on empty lakes. There’s a heavy sense of sorrow in almost every poem, his verse steeped in nostalgia and longing for a country that he’s since returned to only once.

I started studying Vietnamese about two years ago. After a few semesters, I was adept enough to try my hand at translation. It was a natural progression: Vietnamese is the language I should have spoken when I was young, and my relationship with my grandfather was one of the most formative and important in my life. In a family of doctors and lawyers and engineers, he and I were the only writers. When I was younger and we lived in the same state, I would read out loud to him. So this winter, I turned to his poetry.

*

These days, it’s not necessary for the literary-minded to be fluent in another language, and many of the works we read are in translation, though we don’t always realize it — their English counterparts having earned their own place in our canon. Usually, the works we run across are translated from Western languages, which means that things like nuance and rhythm can cross over without too much being lost. Of course, reading Neruda in Spanish or Baudelaire in French is a vastly different experience than reading either in English. Yet even in translation, generally, the shape of these works remain, due to the underlying similarities of the structures of the languages themselves.

But the age of Eurocentrism is (hopefully) nearing its end and literature from other countries will continue to be more and more available (once again, hopefully). Yet in reading translations of contemporary poetry written in non-Western languages, I’ve noticed that they often feel the same. In even the best translations, some lines seem to grasp for meaning, oblique and guarded, as if a thin but impenetrable film had been drawn over the text. Conversely, some lines are beaten into flat but angry and archaic cries, that don’t seem familiar here nor there. These poems feel… translated. They’ve lost their immediacy somehow. English just isn’t adequate — or it is, but we aren’t doing it right.

Part of this is certainly the colonialist history of the translation of non-Western literature. The works of Rumi provide an instructive example: though translations sensitive to the original text do exist, many are actually versifying from extant, older translations. When we read Rumi, unless we’re reading a Nader Khalili translation, or another writer who speaks Farsi, we’re encountering a text that has been run through several generations of translation and versification, a text that has undergone transformations in an effort to make it more accessible to Western readers. The Rumi translations by Coleman Barks are the ones most are familiar with, yet Coleman Barks does not speak or read Farsi.

Compare these two published translations of the same text by Rumi:

if you stay awake

for an entire night

watch out for a treasure

trying to arrive

you can keep warm

by the secret sun of the night

keeping your eyes open

for the softness of dawn

— Excerpt from Ghazal (258), translated by Nader Khalili

Don’t go to sleep one night.

What you most want will come to you then.

Warmed by a sun inside, you’ll see wonders.

Tonight, don’t put your head down.

Be tough, and strength will come.

That which adoration adores

appears at night. Those asleep

may miss it. One night Moses stayed awake

and asked, and saw a light in a tree.

— Excerpt from Ghazal (258), adapted by Coleman Barks

Setting aside the question of two subjective metrics, quality and accuracy, it’s clear that these translations, these representations of Rumi’s “Ghazal (258)” were written in different contexts. How many of these first translations were done under British colonial rule, under the weight of orientalism, under the weight of biases against the value of non-Western poetry? How many of these translations were done by academics who considered themselves correcting the “defects” in the original poetry? And how does this affect how we read translated poetry now?

Existing biases regarding the value of non-Western poetry are still prevalent today. Once, a poetry professor of mine held up two anthologies for our class: contemporary American poetry and contemporary global poetry. “One of these will be useful to you,” he said. It wasn’t the anthology of global poetry — that one, he said, was less valuable. And through whose fault is that? Translated poetry seems caught in an old age, a colonialist, archaic age, even though translations such as Khalili’s demonstrate a richness and freshness akin to contemporary poetry written in English.

*

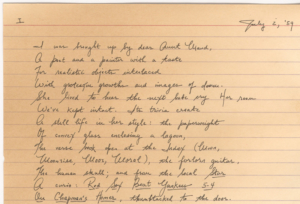

My grandfather writes in a Chinese form, qilu, regulated verse with eight lines of seven beats each. It’s a small, compact, but ultimately dense, form — and it’s difficult to unpack. You have to unfold and unwrap each syllable in order to translate them into the English, the language I use for my own.

Take the title of this poem: “Thu Nhớ Bạn.” Thu means autumn. Nhớ means remember. Bạn means you, as an means of address, but it can also mean friend. How do you translate this?

“Remember autumn, friend?”

Or, “In autumn, I remember you?”

Or, “Autumn remembers you?”

Already, the meaning is unclear — the syntax of the sentence implies any of these titles, but a choice has to be made. If a poem is a bud, translation is guessing what flower it will bloom into.

I ended up translating the title as “Remembering you in autumn.” It’s clunky, but I felt it was as close as I could get to the original. English is a wordy, busy language that needs conjugations and connectors — Vietnamese dispenses with them entirely.

And what about cultural references? “Thu Nhớ Bạn” starts with a specific image, of a woman standing on the shore. When I called my mother about it, she could only answer with a story. “It’s about waiting,” she finally said. “It’s about waiting for someone to return, but they never do.”

What do you do when a poem references a history that you can’t possibly summarize in a few words? What do you do when a poem references a cultural legacy you can only barely begin to explain? In Nabokov’s Pale Fire, John Shade’s epic poem — which in the fiction of the novel does not carry the burden of translation — is elaborated upon in Kinbote’s extensive commentary, through which we begin to understand the story of Zembla. I was not writing of Zembla, but of Vietnam — but how I wished I could add my own lengthy appendix to each line.

In another poem, I realized that I was missing words for missing. I had translated the first seven lines fluidly, based as they were in impressionistic images, but the last line, dealing with the nostalgia and longing felt — the resolution, the crux of the poem — left me grasping for words. “Lòng hướng về sâu nhớ đậm đà,” my grandfather wrote. I called my mother again, this time over Skype.

“It’s a longing for your home country,” she said. “But it’s dense, it’s thick in your heart.” I put my hand on my chest and tried to imagine a tug. “It’s a pull. It’s strong.” A tactile missing. A missing so strong you can feel it in your blood. I didn’t know if I had the words for it. I read various versions of the line out loud, and each time, my mother shook her head. They fell short. If they worked in content, the form was off; if the form felt right, there was something missing in the meaning.

“My soul pulled longingly towards home.” I settled on that translation, trying to marry my own aesthetic with my grandfather’s formal verse, but even now the ache feels a little off. The terms we have for longing, I decided, while trying to translate my grandfather’s poems, are not sufficient. Or maybe it was just my own fault: having not experienced this specific and profound missing before, I lost the nuance in translation.

*

Ezra Pound famously translated a book of Chinese poems (that had themselves been translated from Japanese), Cathay, despite not being particularly familiar with the Chinese language. Though criticized by some for adding lines to his translations that had no basis in the original text, others argue that Pound wasn’t contributing so much to translation as he was to modernism. Certainly translation is a fine jumping-off point for this kind of experimentation — the original text provides a framework upon which language can be imposed and constructed. Because of the syntactic differences between these languages, there’s room for interpretation. There are different ways of seeing, but that difference must be acknowledged, or we risk slipping into misrepresentation.

I don’t know if my translations of my grandfather’s poems are mine now, or if they are still my grandfather’s. But I have to remember that poetry is poetry. In any language it ought to do the things poetry does: hush you, move you, retain its sonic prowess. I try to remember that translation is infinitely recursive. We translate these words into other words. Sentiments blur and change; the poem in Vietnamese is not the poem in English is not the poem in French. This is something to accept.

I would like to say that I have learned that translation requires sensitivity, and I do think it does. To give the reader the same experience in one language that she has had in another. But it’s more than that: the poem will always fundamentally be a different experience, and in that regard, translation is a wonderful liminal space for experimentation.

In translating my grandfather’s poems, I am representing him as much as I am representing myself. The ownership of these texts flips back and forth. There is no “true” or “right,” only truer and righter. There is no end point. We are always approaching.

Thu Nhớ Bạn

Ôm con thiếu phụ sợ thu về

Đơn nhạn lưng trời cánh mỏi mê

Vàng rụng cành trơ nơi biển bắc

Sầu đơm mây trắng khắp sơn khê

Tiếng than đâm thủng tường thương nhớ

Vách hận xây thành dạ tái tê

Trói buộc thanh danh tàn cuộc chiến

Hờn căm chưa trả bạn đâu hề.

Nguyễn Đình Nhạc

Remembering You in Autumn

Holding her child, she fears autumn’s return

A lone swallow tires in the midst of the sky

Golden leaves fall, bare branches against the North Sea

Sorrow hangs low, white clouds paint the mountain air

Grief pierces the wall of memory

Bitterness builds its numb enclosures

Bound into grief from the brutal war,

Revenge I can’t yet take: where are you?

[Translated by the author]

This post may contain affiliate links.