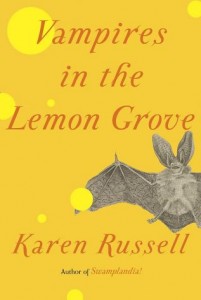

What to say about Karen Russell that hasn’t already been said? A brilliant wunderkind, fantastically original with a sparklingly inventive voice, shortlisted for a Pulitzer Prize in 2012 — where Swamplandia! went up against both David Foster Wallace’s posthumous Pale King and Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams in a wild trio that reportedly threw the board into such a tizzy there was no prize for fiction that year. So her second short story collection, Vampires in the Lemon Grove, has a lot to live up to — perhaps why this collection sees Russell moving out of the murky Floridian swamps and into what seem to be much darker territories.

The collection opens with the titular “Vampires in the Lemon Grove,” a story whose threat, if mild compared to some of the later pieces, sets us up for what’s to come. This one opens in Sorrento, Italy, on an old vampire sitting alone on a bench. The first paragraph opens flowery, fragrant, and ends with an ironic twist of the lips:

I’ve been sitting here so long their falls seem contiguous, close as raindrops. My wife has no patience for this sort of meditation. “Jesus Christ, Clyde,” she says. “Get a hobby.”

And we’re off. This story ends, like so many in the collection, on a, not to spoil anything, but surprisingly literal cliffhanger. Russell leaves off nearly all these stories in the middle of an action, ending on a freeze frame that leaves us — readers and characters alike — reaching for what will happen next.

“Vampires in the Lemon Grove,” if you can believe it, is one of the weakest stories in this collection, which, in a collection as strong and coherent as this one, is only relative. The true dazzlers here are the stories in which Russell goes for the emotionally wrenching knife twists in the gut. This we experience with the imprisoned girls who take control of their own insectoid transformations in “Reeling for the Empire,” the mad run across the plains and horrifying conclusion of “Proving Up,” or the transference of traumatic memories in “The New Veterans.”

The final story in the collection, “The Graveless Doll of Eric Mutis,” represents one of Russell’s most ambitious moves yet. She’s told many stories from the emotional turmoil of an adolescent boy tormented by figures both imagined and all too real in stories like “Haunting Olivia” and “from Children’s Reminiscences of the Westward Migration” in her debut collection, but “The Graveless Doll” is told from the point of view of Larry Rubio, a schoolyard bully and one of the tormentors of Eric Mutis. Before the story begins, Eric Mutis has been the favorite subject of Larry’s physical and emotional bullying until he stops showing up at school — although whether Eric has moved, been kidnapped, or died is not particularly clear. When a scarecrow formed in Eric’s likeness shows up in Friendship Park, New Jersey, Camp Dark — Larry’s “gang” — decides to experiment with the scarecrow by tossing it into the nearby ravine. Over the next few weeks, parts of the scarecrow go missing as Larry becomes more and more terrified and guilt-wracked while we slowly learn the specifics of his interactions with Eric Mutis, until the conclusion’s moment of crisis, mythological in its intensity.

It’s not the plot that makes this story ambitious, but the gentleness with which Russell treats Larry’s interiority. Earlier in the story, Larry remembers watching the morning news, and seeing “a foreign soldier watching blood spill from his head . . . Where was the cameraman or the camerawoman? Who was letting the soldier’s face dissolve into that calm?” “We desperately needed this quiet that only our victims could produce for us,” says Larry of the reasons for the bullies’ cruelty, and by this point, it’s not a sociopathic teenage droog speaking. We know he’s telling the truth, and again — who is letting this happen? What has forced them into the need for this calm? And so Russell demands our sympathies for both the victims and performers of cruelty who, sometimes, are victims themselves.

“Fantastically original,” and for all its triteness I mean that in the sense of both “excellent,” and “fantasy”: Russell, after all, is known for the surreal elements she weaves into her stories. And it is through these elements, perhaps — through the eyes of a horse who thinks he’s an American president, under the gaze of a straw-stuffed doppelganger, as we spin the cocoons that will give us wings — that we might learn what it means, as Larry Rubio says, “to be humans together,” if only for a minute or two.

This post may contain affiliate links.