At this point, it seems everyone in America has something to say about the movie, even those who haven’t yet seen it (like a certain crabby Knicks fan who shall remain nameless). For someone such as myself, who holds Quentin Tarantino up as the greatest filmmaker working today (other than maybe the Coen Brothers), it’s been a blast watching the shit-storm stir around his latest twisted masterpiece.

As much as I’ve enjoyed taking part in the larger debate over the racial and historical politics surrounding the film, I would like to use my space here to address a specific point made about Tarantino that has been driving me up the wall since first I came across it a couple of years ago. It has to do with the regard that many hold Tarantino in: that he is a shallow filmmaker; that he makes movies full of sound and fury, which signify nothing.

You would think that the various debates that have sprung up around Django Unchained would be enough to disprove this lazy criticism, however, it’s one that remains prevalent. In one of David Foster Wallace’s most popular pieces of cultural journalism, David Lynch Keeps His Head, Wallace ends up comparing his main subject to Tarantino. Here is the conclusion that Wallace comes to:

“Quentin Tarantino is interested in watching someone’s ear getting cut off; David Lynch is interested in the ear.”

That’s probably the most famous line from that essay, and one I see trotted out every time a new Tarantino film is released. And I can understand why: it’s a damn good line. It’s funny and it’s succinct, and it would be pretty insightful if it weren’t for the fact that it’s flat-out wrong.

The films to which Wallace is referring are David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) and Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992). The second part of the sentence refers to the discarded human ear which is discovered at the beginning of Blue Velvet and kicks off the plot. There’s no disputing Lynch’s fascination with the tactile object — Wallace is perfectly able to distill and express what makes Lynch’s brand of surrealism unique. It’s the set-up of his declaration, which refers to the infamous scene in Dogs, wherein the psychotic Mr. White uses a straight-razor to hack off a captive police officer’s ear, all to the sounds of Steel Wheeler’s ‘Stuck In The Middle With You’, where Wallace ends up undercutting his entire point[1].

That scene is not only still the most iconic Tarantino has ever shot, it’s also one of the most misrepresented in all of film history. In the same way people misremember certain lines in films (“Play it again, Sam”), they seem to forget what they actually were shown. Back when the film first came out, that scene apparently caused people to faint, vomit and walk out of theaters in droves. Wes Craven expressed his disgust at watching a man’s ear get cut-off. Wallace likewise seems to find the spectacle gratuitous. That’s a fair enough reaction, except for one little thing:

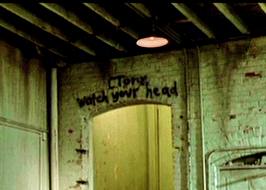

You don’t actually see the man’s ear get cut off. Tarantino doesn’t show it. He doesn’t show the blade moving into the flesh, he doesn’t show the blood pouring out, he doesn’t even show the two men struggling as the mutilation occurs for more than a quick second. Instead, during that most infamous of scenes which people have convinced themselves they actually saw, the camera very noticeably moves over to the top of the wall behind them, focusing on a bit of graffiti that reads: WATCH YOUR HEAD.

We don’t watch a man’s ear getting cut off. Instead we notice the movement of the camera. We are brought to this visual punchline. We hear the sounds of the cop’s muffled screaming and the gruff demanding of Mr. Blond for him to hold still, as well as the sounds of ‘Stuck In The Middle With You’ mingling with the human suffering. But we never actually watch the ear getting cut off.

We don’t watch a man’s ear getting cut off. Instead we notice the movement of the camera. We are brought to this visual punchline. We hear the sounds of the cop’s muffled screaming and the gruff demanding of Mr. Blond for him to hold still, as well as the sounds of ‘Stuck In The Middle With You’ mingling with the human suffering. But we never actually watch the ear getting cut off.

Wallace not only gets this scene technically wrong, he also disproves his own point: in this scene, Tarantino is interested in everything but the physical violence. He’s interested in the technical formalism of the medium, he’s interested in transgressive black humor, he’s interested in human power dynamics, he’s interested in the sense of surrealism that comes from juxtaposing violence with kitschy pop, and he’s interested in the very real horror that is caused by violence.

Late in Wallace’s Infinite Jest, a character has his eyelids sewn open so that he can watch as he is further mutilated and murdered. The description is pretty graphic. Would it be fair to say that David Foster Wallace is only interested in watching a man’s eyelids sewn open? Of course not. So what leg does he have to stand on when accusing Tarantino of such a shallow interest in violence[3]?

Wallace was, without a doubt, a moralist. Tarantino is, without a doubt, not a moralist. These two schools of artists have never gotten along and it’s a fool’s errand to try and bridge such a gap.

The second part of the answer, I think, relates to the difference in the two gentleman’s chosen medium of artistic expression. Wallace was well-known for being an anti-snob in his literary tastes, going so far as to assign such populist bestsellers as Red Dragon and The Stand to his students. Yet it seems that he does not give the same respect to artists in the medium of film. His Tarantino dis isn’t the only example of this; there’s also a quote from him accusing Paul Thomas Anderson of giving into a grad-school sense of artistic pretentiousness in his film Magnolia. That’s a fair enough critique, but it’s one that could just as easily be leveled against any of Wallace’s books, especially the ones he wrote in grad-school.

In an interview with the New York Times during the release of Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino, when addressing his tendency to not judge his characters morally[4], said the following: “I just want the same freedom that a novelist has. You can write a novel about a bastard, but it can be totally interesting.” I would argue that same can and should be said in regards to violence. No one is rushing to judge Wallace’s scenes of horrific violence, which are plenty. They ought to give the same deference to filmmakers such as Tarantino.

[1] To argue with another part of Wallace’s take: he claims that Lynch is one of the bigger influences on Tarantino’s films, going so far as to say that the ear cutting scene is directly influenced by Blue Velvet. This might not be the case; however much of an influence Lynch had on Tarantino (and I honestly don’t think it was much at all), the bigger influence comes from exploitation films which have been depicting the kind of surreal violence Wallace chalks up to Lynch for far longer than Lynch has. This includes the original Django, which contains a scene where a man gets his ear cut off. And then subsequently fed to him. And then he gets shot in the back. It’s a pretty sweet movie.

[2] Which is not to say the man isn’t interested in violence, clearly he is. But it’s overtly dismissive to charge it as shallow. It is often times sadistic (as in the head shooting scene in Pulp Fiction, which is played for laughs), it is often times critical (the casual violence of chattel slavery in Django Unchained); it is often times realistic (the long, slow, utterly unbearable pain of a gut-shot wound in Reservoir Dogs), banal (the car trunk scene in Jackie Brown), and cartoonish (the spraying fountains of blood in Kill Bill). It can be used to repulse and horrify us (the first murder in Death Proof) or give us powerful catharsis (killing Hitler and the German high command in Inglorious Basterds). No one has explored the full range of cinematic violence like Quentin Tarantino. To charge it as shallow is to ignore all of the evidence, to say he’s only interested in seeing the ear get cut off is to miss the goddamn point entirely.

[3] There is some moralizing on QT’s behalf in terms of how a lot of the characters in Django Unchained are portrayed. But come on, they’re goddamn slave owners.

This post may contain affiliate links.