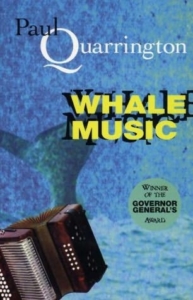

Published in 1989 by Doubleday Canada, Whale Music by Paul Quarrington sets up an age-old artistic problem: artistic autonomy versus the interests of the marketplace. The novel examines the life of musical savant Desmond Howell, who reflects both on his once commercially successful rock’n’roll career with The Howl Brothers and its fallout, made explicit through Desmond’s discussion of his frequent substance abuse, his failed marriage, the untimely death of his brother and bandmate Danny, and his reclusive withdrawal into his seaside mansion.

Published in 1989 by Doubleday Canada, Whale Music by Paul Quarrington sets up an age-old artistic problem: artistic autonomy versus the interests of the marketplace. The novel examines the life of musical savant Desmond Howell, who reflects both on his once commercially successful rock’n’roll career with The Howl Brothers and its fallout, made explicit through Desmond’s discussion of his frequent substance abuse, his failed marriage, the untimely death of his brother and bandmate Danny, and his reclusive withdrawal into his seaside mansion.

Desmond dedicates his time to the composition of what he believes is his magnum opus, the titular “Whale Music.” But Desmond’s record executives say that he isn’t producing commercial, and therefore profitable, music. As a result, the tension between Desmond’s desire to attain cultural capital and the execs’ desire for economic capital becomes untenable, particularly as repeated visits from outside individuals (save his Torontonian houseguest Claire) increasingly impede upon the autonomous creative universe that he desperately wants to maintain. Desmond acknowledges this disparity between his desires and those of the execs in the novel’s opening pages:

I must work on the Whale Music. The Whale Music is very important to me. It’s the only think that’s important to me. Don’t try to stop me from working on it like…countless record executives have tried to do. The record execs say the Whale Music isn’t commercial. I say it’s not my fault if whales don’t have any money.

Using a comic tone to communicate rather tragic circumstances — for instance, his labors in music (over which he only has partial control) are Desmond’s sole means of fulfillment — the novel evokes a style akin to that of John Kennedy Toole. And like Toole, who won the Pulitzer for A Confederacy of Dunces in 1981, Whale Music also received a major literary award, Canada’s prestigious Governor General’s Award, in 1989, placing Quarrington in the company of former winners Alice Munro and Margaret Atwood. Five years later, in 1994, the novel was adapted into a feature-length film, with Quarrington on board as the film’s screenplay writer. The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Adaptation at the 1994 Genie Awards, with Maury Chaykin, who played Desmond Howell, taking home the award for Best Actor.

However, instead of building on its initial success, Whale Music has fallen somewhat by the literary wayside. Once deemed “the greatest rock’n’roll novel ever written” by Penthouse, the novel is now rarely mentioned by literary scholars and commentators. While some of Quarrington’s other works, such as King Leary, which is often called “the great hockey novel,” have received considerable attention from critics, writing on Whale Music rarely ventures beyond succinct summaries or reviews. These tend to focus more on illuminating the novel’s plot structure than its critical or social function. (One of the longest summaries comes from Quarrington’s website.)

For example, Brian Busby’s Character Parts: Who’s Really Who in CanLit (2004) gives Whale Music some very good and useful scholarly attention, but even this is brief: Busby includes a short, two-paragraph description of the parallel between Desmond Howell and the real-life individual upon whom he is allegedly based, Brian Wilson of The Beach Boys. Many other reviews or interviews with Quarrington center on his battle with lung cancer, the disease that, sadly, ended his life in early 2010.

It is a shame that Whale Music is not widely read today. It is humorous and poignant and offers an original insight into the life of an artist and how art is produced. It also beautifully captures the first-person subjectivity of the artist at a time of personal crisis. The protagonist himself is also incredibly endearing and someone who the reader cannot help but like.

However, these very strengths may have led to the novel’s current marginality. Quill & Quire writer Scott MacDonald, for instance, argues that the use of comedy in order to communicate sad, troublesome ideas, does not sell well in Canada. And so it goes, he argues, that Whale Music has significantly faded from view. And it seems unsurprising that a Canadian novel that does not do well in its own literary marketplace will not be a success across the border.

On a grander scale, it appears that the literary marketplace has not been particularly welcoming to narratives about fictional rock’n’roll stars in the last several decades. Rather, a plethora of auto- and historical musician biographies have emerged — such as the critically acclaimed Just Kids by Patti Smith (winner of the 2010 National Book Award), Life by Keith Richards, Robin Kelly’s Thelonious Monk, and Pete Townshend’s Who I Am, to name a few — that seem to fully satiate the reading public’s want for an insider’s look into the life experience of musicians. Some recent novels, such as Dana Spiotta’s Stone Arabia, do indeed feature a fictional rocker, but that novel is as focused on the musician’s familial circumstances as it is on his professional ones.

In a way, this movement away from fictional rock’n’roll characters parallels the essence of Desmond’s plight. Just as there isn’t as much of a commercial space for Desmond’s highly technical, abstract “Whale Music” (much of which Desmond discusses using music theory terminology), the space within the literary marketplace for fictional rock’n’roll narratives has given way to the highly profitable nonfiction rock’n’roll narratives. What’s more, these nonfiction narratives seem to mainly focus on providing a more personal account of how an individual came to make music (e.g., through backstories, childhood experience, and the like), rather than focusing on the structure and production of the music itself. Exceptions certainly emerge, however, such as David Byrne’s How Music Works, which was recently featured in a great piece written for this blog.

None of this is to say that such a shift in focus is a mistake or that there is no artistic merit in memoirs. But I fear that peripheral novels like Whale Music will eventually slip into full-fledged obscurity should they remain unmentioned. The reading public would certainly be at a loss should such a wonderful work as Whale Music, in the words of Mr. Townshend, fade away.

This post may contain affiliate links.