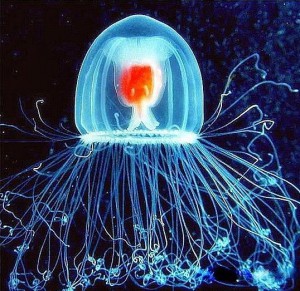

The story reads like Jules Verne: on the sandy floor of a warm sea, an animal known as Turritopsis dorhnii is born. As a young polyp, Turritopsis resembles a soft, branching stalk of coral. As an adult, it morphs into a tentacled, jellyfish-like bulb called a medusa. Marine biology classifies this species among the hydrozoans: small, predatory invertebrates that also include ferocious Portuguese man-o’-wars. But Turritopsis isn’t known for its viciousness; in his superb New York Times Magazine feature, Nathaniel Rich compares their size to a pinkie nail. No, what makes this animal extraordinary is that at the end of its life, the medusa curls up into a blob not to die, but to start afresh. The blob turns into a polyp, and develops on from there. This is why Turritopsis is sometimes called the Benjamin Button jellyfish. It does not die. We just don’t know how.

The story reads like Jules Verne: on the sandy floor of a warm sea, an animal known as Turritopsis dorhnii is born. As a young polyp, Turritopsis resembles a soft, branching stalk of coral. As an adult, it morphs into a tentacled, jellyfish-like bulb called a medusa. Marine biology classifies this species among the hydrozoans: small, predatory invertebrates that also include ferocious Portuguese man-o’-wars. But Turritopsis isn’t known for its viciousness; in his superb New York Times Magazine feature, Nathaniel Rich compares their size to a pinkie nail. No, what makes this animal extraordinary is that at the end of its life, the medusa curls up into a blob not to die, but to start afresh. The blob turns into a polyp, and develops on from there. This is why Turritopsis is sometimes called the Benjamin Button jellyfish. It does not die. We just don’t know how.

For decades, Dr. Shin Kubota has painstakingly cultured these minisculum at Kyoto University’s marine biology lab, in search of the answer. As Rich reports, it is a project no other scientist in the world has successfully undertaken. Then again, few modern scientists share, or at least vocalize, Kubota’s type of passion for their subjects. The potential he sees in Turritopsis is of sublime proportions. Rich writes that in one conversation, Kubota put it this way: “The immortal medusa is the most miraculous species in the entire animal kingdom. I believe it will be easy to solve the mystery of immortality and apply ultimate life to human beings.”

Other experts roundly disagree, but that hasn’t dissuaded Kubota. In fact, he’s become the species’ spokesman. When he’s not tending to his cultures, Kubota himself transforms into “Mr. Immortal Jellyfish Man,” performing original songs about Turritopsis in local bars and television programs, wearing at times a rubber cap with tentacles, at others an apron printed with his own Turritopsis artwork.

Why is Kubota so single-minded? “That’s easy: he wants to be immortal,” Rich later said in an interview. “More specifically, he wants to be 20 years old again. He told me this about 80 times during the week I visited him.”

Make no mistake: Kubota’s research is legitimate, and up to the standards of his field (you can check out his long list of publications here). At the same time, his seemingly quixotic approach resonates with how science worked centuries ago. I think of Carl Linnaeus, the eighteenth-century Swede famous for laying out binomial nomenclature and the basis of modern taxonomy. In life, Linnaeus was primarily a botanist, often a bizarrely obsessive one. In an introduction to a thesis on pollination, he wrote:

Yes, Love comes even to the plants. Males and females, even the hermaphrodites, hold their nuptials… The actual petals of a flower contribute nothing to generation, serving only as the bridal bed which the great Creator has so gloriously prepared, adorned with such precious bedcurtains, and perfumed with so many sweet scents… When the bed has thus been made ready, then is the time for the bridegroom to embrace his beloved bride and surrender himself to her…

But however eccentric the style, the form of Linnaeus’s taxonomy, with its hierarchical classifications (you remember: kingdom, phylum, class, &c.), has shaped how science still studies the living world. Furthermore, his system implied relatedness between species, which would later inform Darwin’s theory of descending evolution. Who knows what a world without Darwin would look like — but it’s unlikely Kubota would be there, chasing Turritopsis.

“Until recently,” Nathaniel Rich writes, “the notion that human beings might have anything to learn from a jellyfish would have been considered absurd.” Linnaeus, who classified nature using observable characteristics, would have chafed. But the Human Genome Project and other studies show our genetic make-ups don’t differ much at all. “The mystery of life is not concealed in the higher animals,” Kubota tells Rich. “It is concealed in the root. And at the root of the Tree of Life is the jellyfish.”

Kubota’s pursuit of immortality may sound like an impractical reason to do science, and there’s a good chance it’s completely in vain. On the other hand, sometimes science needs a nut to shift the paradigm. Today, we chuckle at Linnaeus’s plant porn. Imagine what they’ll be laughing about in another three hundred years, as they hit rewind on their endless days

This post may contain affiliate links.