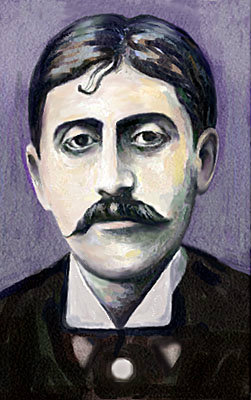

Marcel Proust is frequently lauded as one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. His epic masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, has been the subject of lengthy debate among scholars for almost a century. Originally spanning seven volumes (the final three of which were only partially completed at the time of Proust’s death in 1922), In Search of Lost Time is a sprawling book capable of striking fear into the heart of all but the most determined reader. While fans often praise “The Novel” for its depth and enduring cultural relevance, Proust’s magnum opus isn’t exactly what most people would consider accessible.

Marcel Proust is frequently lauded as one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. His epic masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, has been the subject of lengthy debate among scholars for almost a century. Originally spanning seven volumes (the final three of which were only partially completed at the time of Proust’s death in 1922), In Search of Lost Time is a sprawling book capable of striking fear into the heart of all but the most determined reader. While fans often praise “The Novel” for its depth and enduring cultural relevance, Proust’s magnum opus isn’t exactly what most people would consider accessible.

So why is Proust’s work experiencing something of a renaissance?

The renowned French author has been flying just below the pop culture radar for some time. From the Proust Questionnaire featured at the back of every issue of Vanity Fair, to Tom Tomorrow’s “Spot the Pretentious Proust Reference” game, Proust holds a unique place in modern culture. Despite this, it seems unlikely that, in an age when attention spans are often measured in mere seconds and popular discourse has been reduced to status updates, Proust’s work would continue to find so many new readers.

“I do think that there has been a resurgence of interest in Proust recently,” says K. Thomas Kahn, humble host of the “2013: The Year of Reading Proust” group over at GoodReads, who also tweets under the alias Proustitute. “First, 2013 will be the centenary of the French publication of Swann’s Way, the first volume of Proust’s masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time. And in those hundred years, [it] has been hailed as one of the finest novels ever written by readers, critics, [and] authors, so I think this anniversary is partially why Proust is becoming more popular — or, if not more popular, at least gaining more media attention.”

As dense as Proust’s writing can be, it’s difficult to dispute the timelessness of the work. The theme of memory central to In Search of Lost Time is particularly relevant in an age where the digital equivalent of approximately half of all the words ever spoken by mankind is generated every day. As we struggle to catalog our most treasured moments in the cloud, Proust’s examination of the temporal nature of memory is particularly engaging.

In today’s always-on media environment, many people are turning to practices originally based on Eastern religions and philosophies to combat stress. One practice that has become increasingly popular in recent years is that of mindfulness, which is itself a recurring theme in In Search of Lost Time. In her posthumously published book, The Weather in Proust, academic author Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick even interpreted Proust’s epic as a Buddhist text. In an age when people are literally burning out from information overload, the thoughtful introspection of In Search of Lost Time could be a welcome diversion from the relentless onslaught of data we face every day.

“In a world like ours — one that sees us inundated on all sides by text messages, alerts, notifications, etc. — I think that there is a lot of resonance with Proust’s own obsession with finishing In Search of Lost Time before his death,” Kahn says. “Even more, I think many of us often feel that time is slipping by us [rapidly] due to how fast-paced our world is, and there is often a sense that we are unable to fully appreciate the experiences in our lives — whether these be [the] more mundane like sitting on a crowded subway or the more profound such as falling in or out of love.”

The fluid and exploratory nature of sexuality in Proust’s work could hardly be more relevant to modern readers. Proust never admitted his own homosexuality during his lifetime — he was outed posthumously following the publication of André Gide’s personal correspondence — but his sexuality strongly influenced the characters of In Search of Lost Time, and Proust’s examination of the complexities of sexual identity translates well to the current conversation.

Many people coming to Proust for the first time will be doing so out of a genuine desire to seek out literature that speaks to us in a way that many contemporary novels cannot. This same desire was recently illustrated by the outcry over Christy Wampole’s sadly misguided op-ed in The New York Times. The scathing reactions to Wampole’s piece demonstrate an overwhelming rejection of the notion that cool über alles is the mantra of Generation Y. In fact, many of the responses to the editorial suggest that most Millennials crave the kind of connection to art, music, and literature that transcends the obvious and strives for something real — a movement some refer to as “the New Sincerity.”

“Proust has an uncanny way of speaking to readers at any point in their lives — heartbreak, loss, happiness, career changes, financial crises, you name it,” says Kahn. “I used to jokingly tell friends and colleagues that Proust was my therapist; now, I wonder if that’s really such a joke at all. Proust helped me through an intense time in my life, and in many ways his own examination of life’s upheavals and its profound joys spoke to me (and continue to speak to me) at just the right moments in my life.”

In The Prisoner, the fifth volume of In Search of Lost Time, Proust wrote that, “The only true voyage of discovery, the only fountain of Eternal Youth, would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to behold the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to behold the hundred universes that each of them beholds…” While Proust’s Narrator was referring to the music of a composer named Vinteuil, this passage could easily describe the sense of voyeurism common to today’s media experience. As people become increasingly comfortable sharing the minutia of their lives with strangers online, we now embark on this voyage of discovery every time we browse the Web. No detail is too private, no thought too personal. Just as we divulge our darkest secrets to virtual audiences, whether anonymously or otherwise, our desire to peer unhindered into the lives and personal dramas of others grows insatiable. Of course, Proust could not have imagined how relevant his words would remain in a time so unlike his own, yet this passage remains particularly prophetic.

While Proust’s elegant prose will no doubt serve as a welcome reprieve from the endless barrage of emails, status updates, and tweets we face on a daily basis, I will be reading Proust this January in an attempt to follow in the footsteps of The Narrator; to slow down and truly appreciate those delicate, fleeting moments that remind us we are alive.

This post may contain affiliate links.