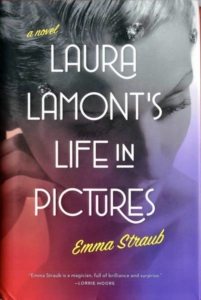

The slim brunette of Emma Straub’s debut novel, Laura Lamont’s Life in Pictures, grows up far from the machinations of Hollywood as blonde, freckled Elsa Emerson in Door County, Wisconsin. It’s a place where women possess a “Norwegian face, which meant it had the look of a woman who had seen fifteen degrees below zero and still gone out to milk the cows.” Laura’s parents own a summer playhouse; by the time she’s 17, she is an old pro on the stage and, along with her actor-husband Gordon, leaves Door County for the glitter of Hollywood. This is the 1930s, the Golden Age of filmmaking, and Laura is both an actress and a woman, a mother of two daughters who is to be re-christened and re-branded into a marketable star.

As she ascends into stardom, Laura divorces Gordon, the man she married during her years of youthful aspirations, and marries Irving Green, the studio executive who discovers her. In Laura’s split identity between her new Hollywood self and her old Midwestern roots, Straub captures the duality of Laura’s existence and, by extension, the dualities of women’s personal and professional lives:

The divorce had been Elsa’s idea, which was to say it had been Laura’s idea too. She found that there were certain activities (feeding the children, taking a shower) that she always did as Elsa, and others (going to dance class, speaking to Irving and Louis) that she did as Laura, as though there were a switch in the middle of her back.

Throughout the novel, Straub makes it clear that Laura’s life is not her own, and decisions are made for her by various men. Late in life, Laura tells a reporter: “When I was young, I made movies because people told me to, and hit my marks, and spoke my lines . . . I did what I was told.” Her realization hardly makes her a feminist icon: she spends the entire novel reacting to and fretting over the men in her life. While in the psychiatric ward after a suicide attempt, she reflects that “Maybe Elsa had wanted to die, but Laura hadn’t, or Gordon’s wife, or Irving’s wife, or Junior’s mother.” Laura, it seems, only achieves self-actualization and personhood when she can define herself in relationship to a man.

Laura’s ingrained politeness results in a repeated denial of her own needs, as when she thinks about the family’s housekeeper: “It seemed rude to impose a friendship on a relationship that already took up so much of Harriet’s time.” And again while trying to find a common thread of conversation with her frigid mother: “It seemed rude to even think about saying something that would make her mother even sadder.” Laura’s continual acquiescence to the needs of others renders her choices predictable, and Straub doesn’t closely examine the duality of Laura’s existence in a way that feels authentic.

Instead, Laura wins an Academy Award for Best Actress and in the tailspin that follows, Straub zips through the big and small moments in the remaining 32 years of Laura’s career, all of which seem made for an episode of E! True Hollywood Story. Laura, no longer a starlet, is embarrassed by a post-Oscar flop, and subsequently suffers an emotional blow at the death of her father, becomes a pill addict, is widowed, attempts a comeback, is blackmailed by her first husband, attempts suicide, spends through her money, gets a job, struggles with her son’s bipolar disorder and his attempted suicide, uncovers a family secret, and mounts a second comeback.

It all happens like a Disneyland ride, one where the reader is buckled into a narrow cart and pushed along on a track past miniature scenes backed by relentlessly tinkling music. The story loses its edge and its urgency; rather than explore specific moments at length, Straub jumbles a hodgepodge of snapshots together. Unlike most Hollywood actors, the more Laura becomes like us mere mortals, the less interesting she is — when it comes to scandals, I’ll take Lindsay Lohan over Laura Lamont any day.

The shining star of celebrity burns briefly (Alyssa Milano, anyone?) and flares only when the once-famous endure humiliations (Britney Spears, Charlie Sheen) and indignities (anyone who has ever appeared on “Dancing with the Stars”) . Laura eventually makes a heartwarming and successful comeback but acknowledges — long after California has lost its sheen and luster for her — that “Nothing stay[s] golden forever.” Unfortunately, Straub’s attempts to make the golden girl of Door County more realistic are expected; the novel never envisages for Laura a story beyond the frequently told Hollywood fairytale-turned-nightmare. When the gold is tarnished and no longer gleams, the audience, and the reader, will be ready to move on to the next shiny thing.

This post may contain affiliate links.