When a well-written book (or movie or TV show or poem or some other narrative or anti-narrative media thing — whenever I say book, assume this parenthetical is here) creates a vivid sense of a world, and you become engrossed in that book, you often say “this book pulled me in,” or “this book drew me in.” This is a metaphor for how a good book feels, and it is such an incredibly common way to express a common feeling that saying a book “draws the reader in” has become cliché; everyone engages in a little anthroposophic thought now and again.

When a well-written book (or movie or TV show or poem or some other narrative or anti-narrative media thing — whenever I say book, assume this parenthetical is here) creates a vivid sense of a world, and you become engrossed in that book, you often say “this book pulled me in,” or “this book drew me in.” This is a metaphor for how a good book feels, and it is such an incredibly common way to express a common feeling that saying a book “draws the reader in” has become cliché; everyone engages in a little anthroposophic thought now and again.

Occasionally, writers and other media creators try to incorporate this feeling into the actual narrative. In the 1984 fantasy movie, The Neverending Story — which I loved and watched dozens of times on the Disney Channel, but never read the book it was based on, sorry — a boy named Bastian steals a book and skips school to read it. Inside the book, a child warrior named Atreyu tries to save Fantasia, the world he lives in, from a consuming force called The Nothing; Fantasia’s ruler, the Childlike Empress, sends Atreyu on this quest. At the end of the movie, as a ruined Fantasia falls apart, Atreyu visits the Childlike Empress to tell her he failed. She schools him: he didn’t really need to save her, just bring her a human child. And where is a human child? Already there, she says. The Childlike Empress, through the pages of the book, calls out to Bastian: “He doesn’t realize he’s already a part of the Neverending Story,” she says.

Then things get really wild. She continues, to Atreyu, “Just as he is sharing all your adventures, others are sharing his.” Us! The viewers of the movie! She’s talking about me! The Childlike Empress recaps little pieces of Bastian’s life we’ve already seen, proving she sees Bastian, while he screams, “But that’s impossible!”

Talking to me and to Bastian, the Childlike Empress says, “They were with him when he took the book, in which he’s reading his own story, right now.” Bastian freaks out: “I can’t believe it! They can’t be talking about me!” But they are talking about him, and if they are talking about him they are talking about me. That is why The Neverending Story is still one of my favorite movies; I’m in it, figuratively and literally drawn in.

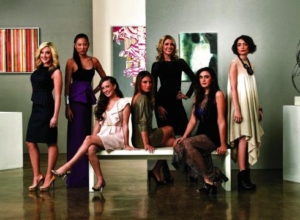

There are lots of ways to be sucked into a narrative, and a lot of different narratives to be sucked into; a particularly jarring way of entering a narrative is by knowing someone on a reality TV show. I went to high school with a girl named Claudia, pronounced KLOW-dee-uh, one of the cast members of Bravo’s new series about New York City art girl feelings, Gallery Girls. Most reality show cast members seem about as real to me as the characters on Revenge, a feeling emphasized by perhaps the best piece of filmmaking ever to come out of reality TV, the final scene of The Hills.

To know, IRL, a person on reality TV forces me to shift people who were, essentially, television characters into the realm of actual people. I get the uncanny valley wiggins. Unreal becomes real, and all of a sudden, the emotions of The Real Housewives become valid, human feelings (albeit ones expressed by dangerous narcissists).

In his book Haunted Media, sociologist Jeffrey Sconce explores the fascinating connection between the rise of mysticism in America and the advent of various electronic presences from telegraphy to television. Sconce examines the “large cultural mythology about the ‘living’ quality of such technologies, suggesting, in this case, that television is ‘alive… living, real, not dead.’” In other words, the boundaries between the real and the unreal are cloudy. As ever, it is more interesting to me to live in a boundaryland rather than stand firmly on side or the other. We are all already part of the Neverending Story, especially you, you who are reading this, right now.

This post may contain affiliate links.